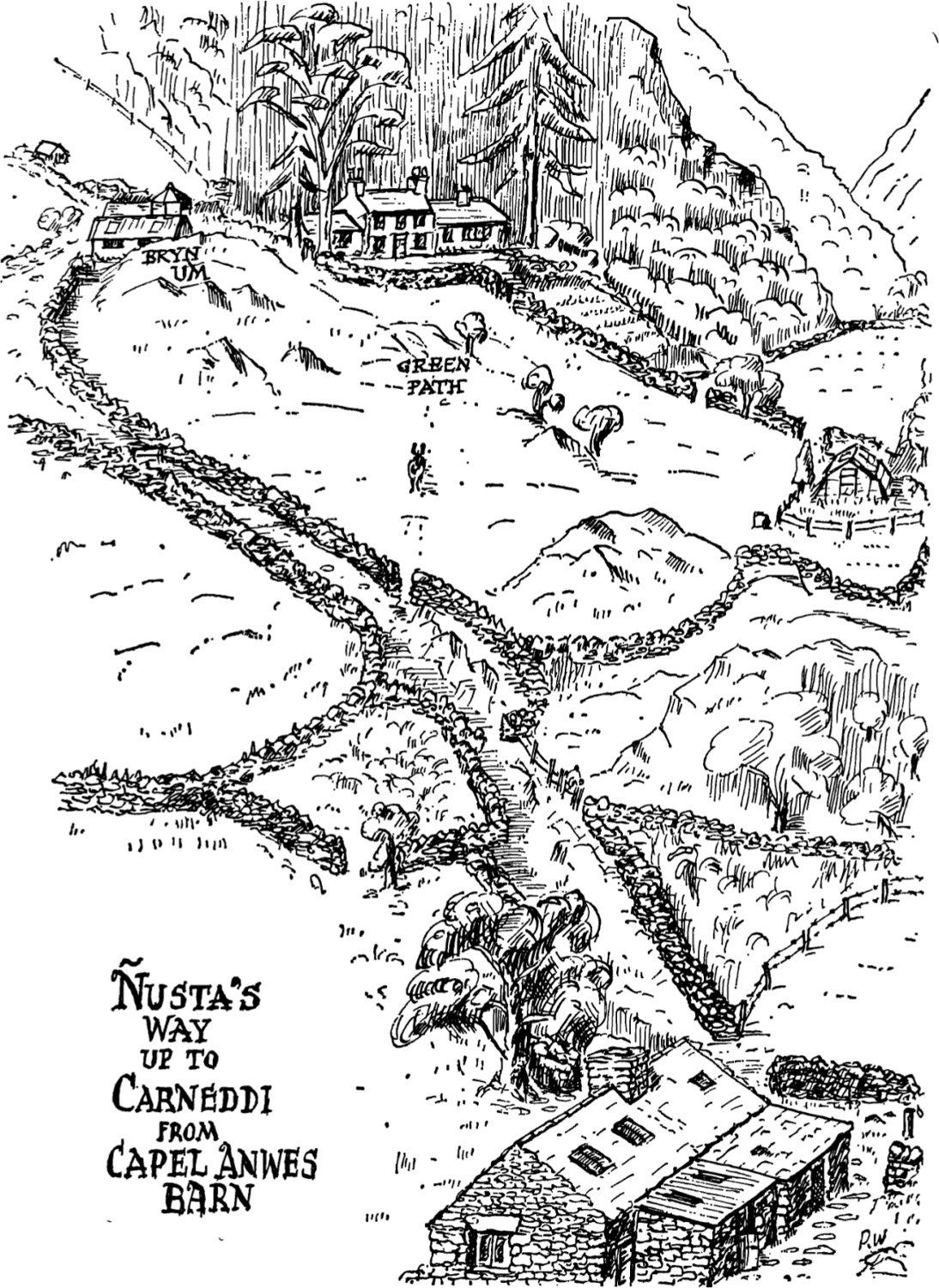

The practical kindness of others has helped me considerably with this book. In particular I would like to express my sincere thanks to Miss B. Fargher and Mr N. R. Ingman, our vets, and to Dr Antice Evans for scientific facts. For illustrations, my gratitude goes once more to Brian Nicholson for preparing the photographs, not only his own but also those kindly given by John Greaves. And to Paul go my thanks again for drawing the pictorial map and for the sketches.

Finally, I acknowledge with gratitude the award of a grant from the Welsh Arts Council for the purpose of writing this book and I thank my friend, Mollie Keen, for her stroke of genius in suggesting I apply for the grant.

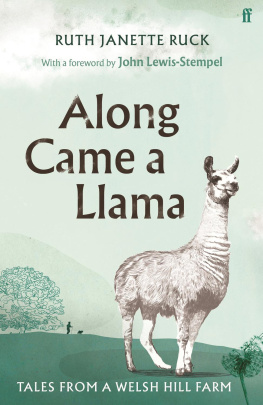

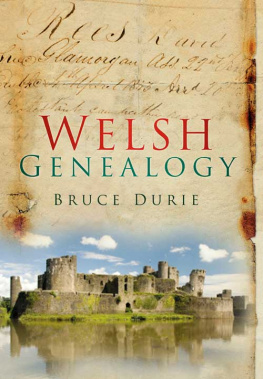

Like its prequels Place of Stones and Hill Farm Story, Ruth Rucks Along Came a Llama belongs to the Back to the Land vogue in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s, which found its most famous expressions in the book Self-Sufficiency by John and Sally Seymour and the television programme The Good Life.

Rucks books depicting life on the 83-acre farm of Carneddi in pluvial, precipitous Snowdonia were simultaneously more authentic and more charming than rival works.

The Ruck story really begins in 1945 when her demobbed father decided to up sticks from suburban Nottingham and relocate to the threadbare grass and hard slate of North Wales. Ruth was seventeen.

Going back to nature, of course, has always been the British way in a crisis; at the end of the Great War there was even government legislation to fund ex-soldiers on smallholdings. The original classic of self-sufficiency was William Cobbetts Cottage Economy, written in impoverished, depressed 1821. Cobbetts book itself was indebted in its philosophy to the Diggers of the world-shattering English Revolution.

So, naturally, we are nature-minded again now: post-crash, post-coronavirus.

Luckily Rucks family took to farming in the mountains of North Wales like a sheep to grass. By the long hot summer of 1976 the year in which the llama of the title came into their lives Ruth had married climber Paul Work and taken over the reins at Carneddi. Around her, even in remote North Wales, traditional farming was disappearing. The Rucks were nearly alone in turning hay by hand, in willing individual sheep known by their faces, their names to live when ill. Everyone else had been mechanized, chemicalized, industrialized; or sold up. The Age of the Big Farmer had arrived. Ruth Ruck, however, was so indoctrinated by the old ways that Carneddi continued as before.

There is food for thought in these pages (which, by the way, are deceptively literary underneath Rucks easy, chat over the kitchen table style). Disciples of Big Farming say that these old ways of agriculture are uneconomical which is an odd criticism from an industry only kept afloat by billions of pounds in subsidies, in which farmers lie awake at night counting not sheep but repayments on a tractor that can easily top 100,000.

Of course, I would agree with Ruck. I still turn hay by hand with a rake. My tractor is 1956 vintage. (The Rucks Land Rover, persistently up to its tricks, also strikes a chord.) I too talk to our animals.

Ruth admits that the hard work put lines on my face and grey in my hair. She does not romanticize her life, but she is alive to its benefits, such as free-range kids who can swim in the stream, and surroundings which are a constant inspiration in their beauty. The phrase she uses about her style of farming is soul-rewarding.

Is there any soul at all in modern agriculture? Any esteem at all for livestock on slats in factory units?

Something else pleasantly, positively, old-style about Along Came a Llama is Ruths mental toughness. In these pages her father dies, her sister Mary dies, and she herself contracts multiple sclerosis. This could so easily have been a misery memoir.

While she does find the MS a sentence on me which I found very hard to bear, instead of wallowing in self-pity she grits her teeth, pulls up her socks and puts on her wellies, as one always does when farming. Her husband, Paul reflecting that he has injected hundreds of sheep, so why not his wife? gives Ruth her quotidian medicine.

There is a llama in the room. Literally. While the Rucks carry on raising sheep, poultry and Welsh black cattle, they do not quite carry on regardless. They buy a llama from Knaresborough Zoo to cheer us up, taking it home in a trailer with no fuss, no paperwork. (You could do fun things like that in the 1970s; today you would need online movement forms and licences in triplicate.)

So, enter usta (Quechan for Princess): a toddler llama, with big eyes and bigger appetite sometimes for rather unusual fodder. (Tissues. Maltesers. Cherry brandy. Tic Tacs. The Radio Times.) Indeed, the very first line is a taster of what is to come: Oh, heck, cried Paul. Its at the sugar again!

The Rucks know nothing about South American llamas from the high country of the Andes; but then again, nor do many other people in the Britain of their day. But the Rucks do understand animals, and they do care: so after some hiccups in llama-raising, usta settles down happily at Carneddi, taking pride of place on the hearth rug next to her toy box, calm, dignified and beautiful, and making her slight musical moos.

To the Rucks existence, already full of soul, usta adds character. Even on paper, travelling across the decades, ustas personality entrances. One departs this book a convinced llama-lover, despite the species camelid reputation for spitting. (usta is far too refined for such behaviour. Usually.)

No dumb animal, usta. Looking into ustas eyes Ruth has the uncanny feeling that there was someone in there, trying to communicate. When usta looked back, she would have seen respect in the eyes of her llama mama.

Care for the environment. Connection with nature. Self-sufficiency. Regard for animals

Certainly, Along Came a Llama has a Durrellian recollection-of-family-life-with-unusual-pet spirit about it. But it is so much more. It is a guide to the future.

To a good life.

Oh heck! cried Paul. Its at the sugar again!

We all made a dive at the animal. Her nose was firmly clamped into the silver sugar-bowl. The sugar was disappearing out of the bowl at the rate one would have expected if the nozzle of the vacuum-cleaner had been applied to it. Paul grabbed the bowl and passed it over the llamas back to me. I hastily put it in the food-safe and shut the door. The llama put her ears back, goggled her eyes and pulled ugly faces, pretending that she was going to spit. Then she turned to the sugar that had been spilt and began to vacuum up the last grains with her quick upper lips. Her ears went forward again.

There wasnt much space in our small kitchen with three of us and the llama. The animal was so big now that her body reached from side to side of the room. Her neck was so long that she could touch all but the upper shelves, where the sugar, flour, porridge oats and cornflakes had now taken refuge.