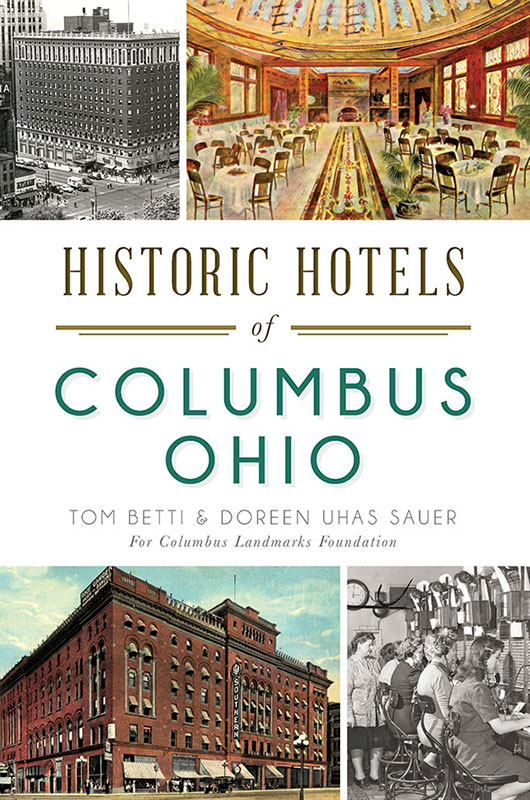

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Tom Betti and Doreen Uhas Sauer

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.423.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015943856

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.896.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is dedicated to the memory of our dear friend (and Hartman Building neighbor) Anne Marshall Saunier, who inspired many, taught us much, listened intensely, had such a passion for life, gave us the truth and laughed at our jokes whether they were funny or not. We miss you, Anne.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

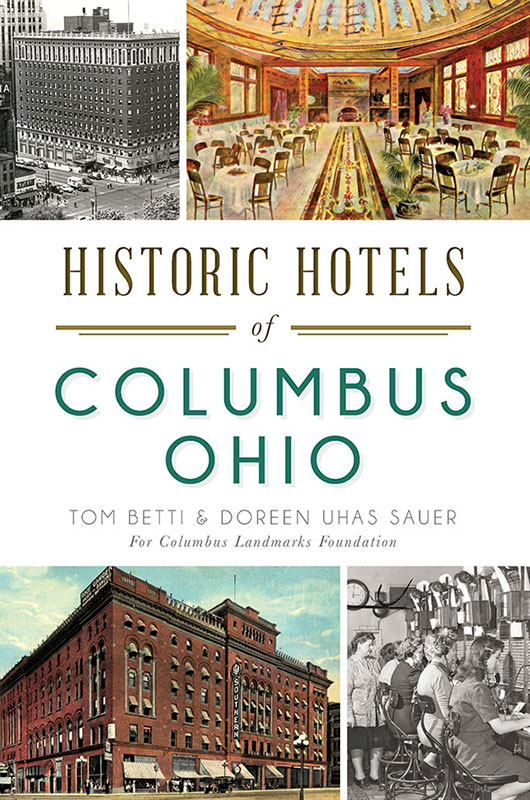

When we decided to write about Columbuss historic hotels, we assumed that the grande dames of a bygone erathe Deshler, the Neil House, the Chittenden, the Hartman and the Great Southernwould make up five tidy chapters. From our writing and researching of Columbuss historic taverns, we assumed that there would be some surprises. We did not expect to find more than two hundred drinking establishments in Columbus in the 1890s. And so it was with hotels.

The more we researched hotels, the harder it became to limit ourselves to just five establishments. When we asked people what downtown hotels they remembered (whether or not the building still existed), a number of hotels surfaced in their memoriesthe Seneca, the Norwich, Fort Hayes, the Northern, the Park and the Metropole. Others were names from their parents memoriesthe Charminel, the Farmers, the Columbus, the Macon, the St. Clair and the Star.

Forget the hotel chains that came to Columbus in the 1970s through the 1990s, like the Sheraton and the Hyatt, and dont even go there with the chain motels like Holiday Inn, Howard Johnson or the mom-and-pop roadside architectural wonders like Forty Winks, the Bambi or the Homesteadwe had enough on our hands.

Tom and I both grew up in Cleveland, a city rich in historic hotels, which may account for our fascination with them. Though more than a generation apart in age, by working together on the board of trustees at the Columbus Landmarks Foundation, Tom and I discovered we shared an affinity for the stories behind buildings, a love of local history and Clevelands immigrant DNA.

While Tom now lives in a condo in one of Columbuss most elegant former hotels, the Hartman, my connection to Columbus hotels is different. I arrived in Columbus thirty years before Tom, and I was fortunate to have seen with my own eyes the Neil House and the Deshler. As a college student boldly curious about making a new city my home, I checked out the lobbies, restaurants, restrooms and especially the watering holes of Columbusplaces for people watching.

Toms fascination with hotels has led him to haunt the finest establishments in Cincinnati; London; New York City; Chicago; Washington, D.C.; and West Baden, Indiana. At these places, it is easy to remember how history has played out for the rich, the famous, the powerful and the pretenders.

My own brush with hotels was more the personal; I worked at the Ohio Stater Inn across from Ohio State University (OSU). Legendary coach Woody Hayes and comedian Jonathan Winters were more than occasional solitary diners on my shift in the middle of the afternoon. Columbus mayor Maynard Sensenbrenner (195459, 196471) had monthly city meetings and appearances at banquets where he handed out American flag pins and kept, in his words, a watch on the university to keep those damned kids under control. (It was the era of jaywalking protests and, later, antiwar demonstrations.) I found out things about hotels I didnt want to know, and I was fascinated by the backstories of those who worked in them and those who frequented them.

A well-known early Columbus TV personality and an honored Catholic Father of the Year had a weekly scheduled nooner at the inn after lunching with his girlfriend. The bartender, Annie, was a voluptuous red-headed Elizabeth Taylor look-alike who had had hard luck stories of her own but mothered all the college waitresses, most of the English Department (drunk or sober) and the many traveling salesmen who could not afford the downtown hotels.

As with any workplace, the people who ran the show behind the scenes had the most compelling stories. The cooks and dishwashers were from Alabama families who arrived with the Great Migration and who now led civil rights pickets at the downtown dime stores on their days off. The three-time married manager who spent his eighteenth birthday in a cockpit bombing North Korea still suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, often while on the job. The hotel manager and part-time hotel dick (detective), the son of a once-prominent Haitian family, came for OSU business courses but could afford to learn business only by working full time.

This is what Tom and I both learned, each in our own way, while researching the book: in reality, hotels are made of a series of rooms where hopes, vendettas, power plays and secrets run like a continuous loop on a projectormuch like history itself. Hotels have livesthey are conceived, born, age, often partner with other hotels, sometimes pass on, become the actual dust in the ashbin of history or are reborn. There were over 125 hotels in downtown Columbus in the one-hundred-year-span from the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. These are only a fraction of their stories.

As with our previous books, Tom and I would like to acknowledge members of the Education Committee of Columbus Landmarks Foundation for all their help and the Columbus Landmarks Foundation board for continuing to support our notion that a brick is just a brick unless there is a story behind it. Special thanks to Ann Seren and Terry Sherburn for passing along stories and research and to the staff of the Local History and Genealogical Society Division of the Columbus Metropolitan Library; they are wonderful, generous, humorous and very knowledgeable people.

DOREEN UHAS SAUER

INTRODUCTION

One morning, in the fall of 1880, a middle-aged woman, accompanied by a young girl of eighteen, presented herself at the clerks desk of the principal hotel in Columbus, Ohio, and made inquiry about whether there was anything about the place she could do. She was of a helpless, fleshy build, with a frank, open countenance and an innocent, diffident mannerAnyone could see where the daughter behind her got the timidity and shamefacedness, which now caused her to stand back and look indifferently away.

And so, Theodore Dreiser, an American realist writer (18711945), opened his novel Jennie Gerhardt (1911). Jennie is an innocent, impoverished young girl in Columbus who will be seduced by George Brander, a United States senator, at the Neil House.

In 1911, sex before marriagemuch less between people of two different social and economic classeswould be told as a cautionary tale, not to be moralistic but to be realistic. No happy ending here. The daughter of German immigrants, Jennie is seduced in the hotel; becomes an unwed mother; goes on to other men, other promises and another love (he marries someone else); loses her daughter; and becomes a silent and secret mourner at her lovers funeral.

Next page