This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1990 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

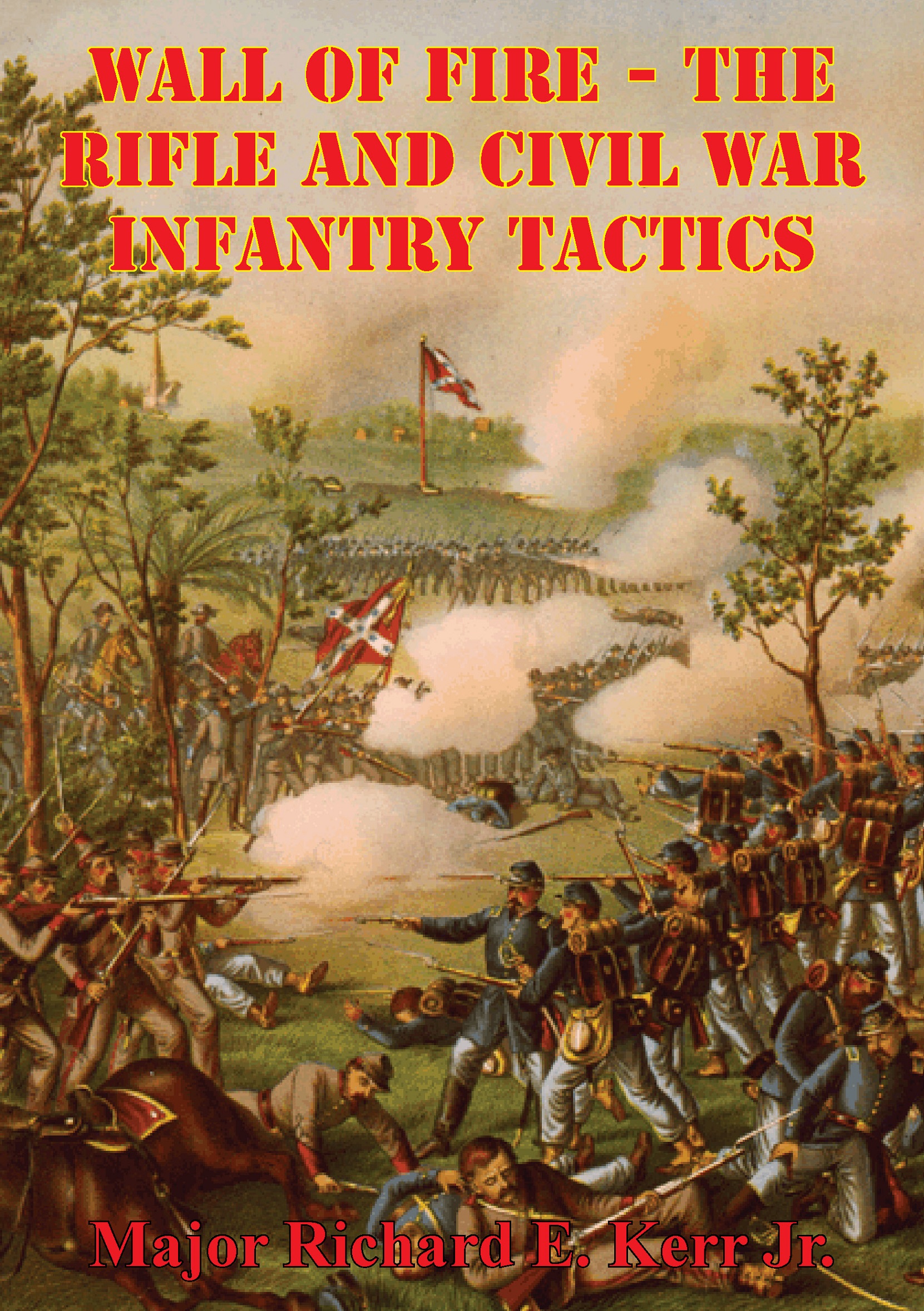

WALL OF FIRE -- THE RIFLE AND CIVIL WAR INFANTRY TACTICS

By

Major Richard E. Kerr, Jr., USA .

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

ABSTRACT

This thesis examines the effect the rifle had on infantry tactics during the Civil War. It traces the transition from smoothbore to rifle and the development of the Minie ball. The range and accuracy of various weapons are discussed and several tables illustrate the increased capabilities of the rifle. Tactics to exploit the new weapon are examined, primarily those of William Hardee. Using Hardees tactics as the standard rifle tactics before the war, the change in how infantry soldiers fought is documented with two battle analyses. The 1862 Maryland Campaign shows the start of tactical evolution as soldiers seek cover, expend large quantities of ammunition and are decisively engaged at greater distances. During the 1864 Wilderness-Spotsylvania battle, the concepts of fortification defense and skirmish offense take hold. Examining several current books that deal with the rifle and its effects, the thesis concludes that the rifles increased firepower was a major factor in the move away from Hardees formation tactics.

PREFACE

Although the battles discussed here happened almost 130 years ago, the frustration of integrating new technology into a force of citizen soldiers and changing doctrine faces us today. My topic is primarily a look at the technology and tactics of the day, and an analysis of how tactics may have been used to overcome the effects of potential new capabilities found in the rifle.

The Civil War took place over one and a quarter centuries ago. Primary sources are limited to operational records and personal correspondence, which often reflect the authors purpose or bias. No newsreels or long recordings exist to piece together the war in a nice, clean, continuous flow of events reflecting tactical deliberations. Because of this, it is difficult to verify that changes in tactical maneuver were caused by leaders recognizing the rifles new lethality.

A universally accepted resolution of this rifle versus tactics question avoids us today. The widely held position, that the rifle caused the high casualties and thus a change in tactics, is confronted by McWhiney and Jamieson in their book Attack and Die and Paddy Griffiths Battle Tactics of the Civil War . McWhiney and Jamieson argue that the high casualties on the southern side were a result of Celtic heritage and Griffith believes that many factors prevented the full application of the rifles capabilities in the last Napoleonic war.

My interest in this subject comes from two staff rides I participated in with Colonel Harold Nelson from the Center of Military History, the Army War College. In April 1987 we walked the Gettysburg battlefield and in May 1988 we did Antietam. At Gettysburg he spent some time discussing linear tactics and the changes brought about by the rifle. I am indebted to him not only for his historical insight, but also his example of a professional soldier.

I am not a historian and lack many of the required scholarly skills that come with the practice of history and the familiarity of ones subject. Armed only with curiosity, my efforts were aided by many people. Dr. Jerry Cooper served as my mentor, director and teacher in the writing of this thesis. He provided guidance, criticism and encouragement in the right amounts at the right time. Faced with a limited amount of time to accomplish this task, I found the entire staff of the CGSC Library of immeasurable help. As I fumbled through, each member of the staff, at some point in the ordeal, provided that missing piece of information or source that I needed to complete this paper.

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

The story of battle has been a continuing struggle between technology and tactics. The march of technology has been continuous since the eighteenth century, with periods of rapid advances in weapons of war. This is of course tied closely to the world wide industrial revolution. As weapons changed from hand weapons and pikes to bows and arrows, muskets, cannons and finally rifled firearms and cannon, there were corresponding improvements in powder and metallurgical processes. These increased the rate of fire, range, accuracy, dependability and maintainability of all weapons.

Weapon technology and tactical application remained relatively stable from the late seventeenth century until the middle of the nineteenth century. By the end of the Napoleonic wars, the rifle was a weapon, whose time had come. When put together with better bullets and ignition systems, it became the dominant force on the battlefield.

The permanent and ever present curse of the soldier is the reaction to and application of this constant evolution of technology. He faces changes from war to war and even battle to battle. What remains steady through all of this is the soldier. New weapons and technologies are still employed by men, who have a natural resistance to change. With only limited options in tactical formations, the soldier must find clever and unique ways (changes, which are hard to implement) to use the new weapons. As weapons increase in firepower, range and accuracy they seem to increase the attacking soldiers vulnerability and make defense the preferable form of war.

These increased capabilities are available to the offense but require some form of protected maneuver that permits the soldier to survive the increased range of the defenders weapons. This newfound capability changes the face of battle on both sides of the line of contact. All other battle and support systems must then be coordinated with this increased capability. Even the defender must adapt his use to the new capability, or risk losing the advantage.

It is often written that defending is the strongest form of war. The increased firepower of the defender is caused by the defenders ability to fire accurately at longer ranges with increased volume. The rifle, coupled with the expanding base conoidal bullet, brought these changes and permitted each rifleman to hold and defend more territory. During the American Civil War it became necessary to have a three to one superiority to triumph over the defense.

If this is true then offensive action becomes more difficult. However, it is only through offensive action that one side seizes the initiative and imposes its will on the enemy. If we assume initial favor to the defender, then it is the soldiers job to negate that superiority and defeat it in some form of offensive action that wins the battle, campaign and the war. As weapons change the face of battle, how does the soldier change the form of battle to maintain parity and survive?

Next page