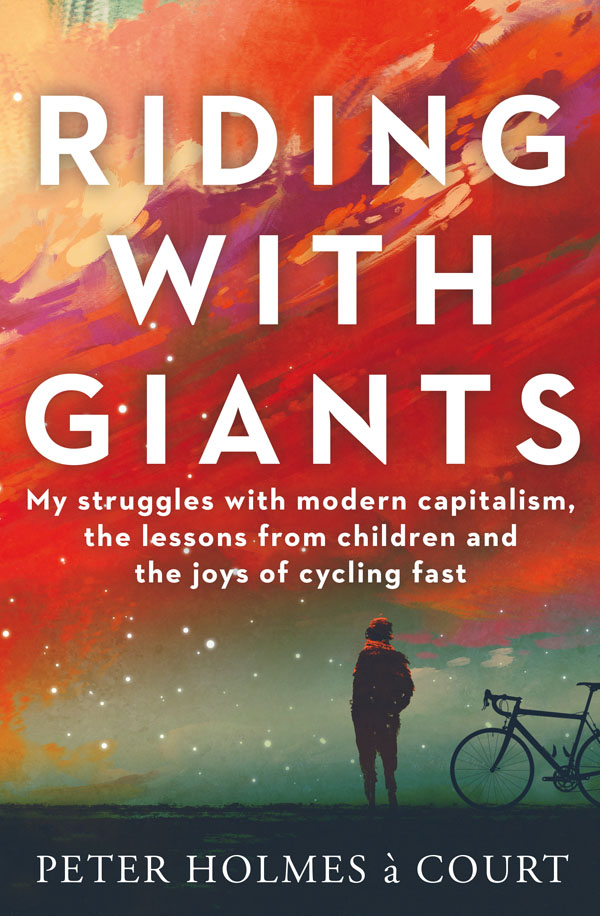

About the Book

When international businessman Peter Holmes Court left the executive world, he found himself living deep in rural France with only his seven-year-old twin girls for company.

Peter was struggling as a single father in a foreign country unsettled by the sudden move away from a traditional job, and completely baffled by the society around him. His only plan: to ride Ltape du Tour , the challenging amateur leg of the Tour de France. In an effort to find some new friends in the community and a bike for the race he discovered the regions small bicycle factory.

He was soon spending his days there: photographing his custom bike being built, meeting the locals, and learning about the rich traditions of artisan craftsmanship. Trying to enjoy the simple things and become a better father, Peter slowed down, and started to reflect seriously on history, industry and the structure of our modern economy. He and his daughters finally began to put down roots and understand the beauty and calm of a small-scale existence and a very different approach to excellence and the well-lived life.

This is one mans compelling, informative and funny story about the wisdom of children, the nature of work today, and the science of bicycles.

The first thing to understand is that capitalism doesnt exist. Talking about free-market capitalism is like talking about the weather or music. It leaves out all the important details: hot or cold, pouring or drought, string quartet or garage band or drum circle?

INTRODUCTION

Sometime in my early teens. Wicketkeeper was where they put me, out of the way.

When I was eleven I was sent 2000 miles from home to a boarding school on the other side of the continent, because, apparently, it was the best in the land. The schools extensive campus spread across a piece of southern Australian coastline. It occupied a low promontory next to Corio Bay, an uninspiring mouthful of Bass Strait, the turgid slice of ocean that separates mainland Australia from its island cousin, Tasmania. Its boarding houses, dining halls, classrooms, chapel and decoratively fortified clock tower were red-bricked monuments to the way things have been, and the way things were sure to stay, settled or so was hoped forever. More English than the English, it was an antipodean facsimile of a British private school, a transplanted piece of Victorian certainty, full of dark corners and sharp edges, with strict rules for uniforms and uniformity. With nearly a century of operations, there was ample evidence of its authority and little room to argue. Its location had been chosen to fortify its students with daily exposure to the sea breezes of the Southern Ocean. Instead, the easterly winds brought the mildewy funk of the bays decomposing seaweed, while the westerlies added the gaseous discharges of the enterprise at the other end of the peninsula: the Shell Petroleum Refinery, proudly Australias largest distiller of auto fuel.

To those expected to be the countrys future leaders, and one who stands to be the next King of England, the venerable institution provided all the requisite markers of the correct education. In reality, it was a morally bankrupt sportocracy with militaristic underpinnings and unenthusiastic religious instruction. We were buttoned tightly, under well-pressed sky-blue uniforms, but the thin facade of unquestioned propriety only barely concealed a deeply embedded system of institutionalised bullying with more than a hint of sexual abuse.

It was all made possible thanks to commercially distracted parents and an unholy alliance of teachers and student prefects. I was not well prepared for my introduction to the curious habits of the Establishment. I was a year younger than most of my classmates, and immature for even that. I was stick thin and bullied regularly. I didnt understand why why me, and why they, the luckiest of the Lucky Country, made the subjugation of the already weak such a serious pursuit. It hurt: hurt my thin arms, dented my exposed ribs, dented my heart and shaped my soft soul. Most of all, it was just confusing.

No matter how bad it might have been for me, though, there was a type of comfort that came with knowing that worse befell others. Today, when the schools administration does write to me, it is either to solicit a donation or reiterate the offers of the free psychological counselling that they provide for students who were abused in deeper ways than I was. To be fair, the school did produce plenty of the type of leaders it was set up to manufacture: independent, articulate and good looking in a blazer, well-rounded in the modern disciplines of commerce and sport, merciless soldiers of industry.

Beginning at around age fourteen, we were required to attend meetings with the schools Careers Guidance Officer. Standing outside his small office at the base of the imposing clock tower, I joined a line of self-assured, well-bred boys who all seemed able to recite a well-reasoned career track for themselves. Often it sounded suspiciously like the one their father had taken. It was a rigid pathway, built on the disciplines of finance and law, a railroad that led with divine inevitability to a corner office in some urban centre of commerce; into a role that would fund at least one house, and the production of at least two children, each of whom were suitably primed to follow their fathers (or in rare cases, their mothers) footsteps back to the school where my consultation was about to take place.

When I began this career tracking, what I really wanted to be was a jockey. As I was approaching six feet tall, I knew I had to find another profession to discuss with the humourless mentor in charge of charting the path of my lifes labour. So, when he asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I said that I wanted to be a photographer I mean, if there is really no way I can be a jockey.

As far as the Careers Officer was concerned, I was making the mistake of speaking the wrong language. I was told I was talking about a hobby, by a man I seriously doubted had any. He sat on the side of the sensible, with the moral force of the Establishment, and as sure as the world spins to the right, I was going to track in the approved direction. Study Maths and English, he said, followed by legal or financial training that would be the sensible path for me. I knew I had as much chance of reversing this force as I did of swimming to Tasmania, so I did as advised, and placed all creative dreams into a small bag labelled Distractions.

For a while, I tried my best to keep my passions alive. I joined the school camera club and filled rolls of 35mm film with my photos. I carefully developed the film and printed the images in the schools darkroom, spending countless hours in the cramped red-lit dark space. To a teenage boy, it was one of the most erotic places I had ever spent time. Paper coated in silver oxide, exposed to light for just the right number of clicks of the timer, darkened in trays of delicious chemicals, gradually revealing my photos on the white rectangles, a few of which were actually in focus.