To my children Tahmoor, Akbar and Aiyla, so youll always have my story.

At the beginning of June 2014, I took a trip back in time.

It wasnt planned. It wasnt for a particular purpose. My father had died six weeks earlier. I had returned to Lahore for the first time since his funeral after seeing Kolkata Knight Riders, whom I was coaching, chase 200 to win the Indian Premier League. The campaign had been exhausting. Now I had a chance to pause, to visit my fathers grave in Model Town, to share the news with family that my wife Shaniera was expecting our child, and to act on a vague homing instinct I had felt for a while a desire to return to the area in which Id grown up, where Id played my first cricket in the street with a tape ball and an old bat. The place of my childhood. The place whose imprint is still on me.

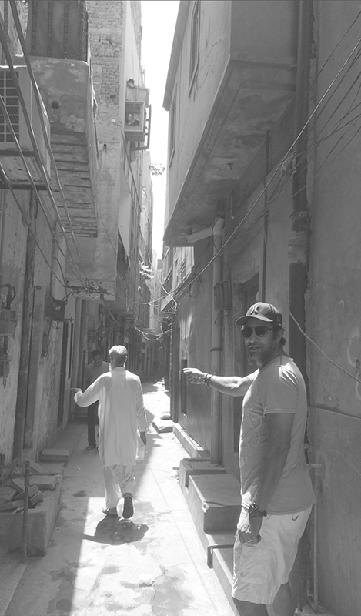

I have been known to do things suddenly. Shaniera likes reminding me that I gave her two hours notice of getting married more on that later. But a spontaneous decision was the only way to make this trip. Had word got out in advance, the frenzy would have rendered it impossible. So I put on a blue T-shirt, tugged on a cap, and a friends driver dropped us on Mozang Road, Mozangs main thoroughfare, near Ahmed Pura bright, busy, crowded, alive. We turned into my old gali, barely a couple of metres from side to side and cast in shadow by three-storey frontages something of a relief from the days heat.

Having not been back for so long, I first of all noticed some changes. Paving had replaced the old red bricks. The open sewering had been covered. Otherwise it was all exactly as I remembered. The tandoor from which I had bought my rotis; the stall that sold what we thought were the best chickpeas in Lahore; the paan shop on the corner supplying the bitter leaf we Pakistanis chew; the mosque where we prayed; the schoolyard where my friends and I sometimes played after hours, except when we were chased away by a Pathan guard with a huge moustache: they were all there. I could have found my way blindfolded.

I started seeing faces I recognised. Where I had bought milk was now run by the former owners offspring; people reappeared who I had played tape ball cricket against, now adults with children, to greet me as though I had never been away. The front of our tiny old house was also unchanged, save that the old green wooden door had been replaced with iron. We knocked and a tiny figure, an elderly mother, answered. I know you, she said with a smile. You used to live here.

I was welcomed warmly, and Shaniera with something like amazement a pale-faced, fair-haired gauri (white woman) was in this gali a rare sight indeed. And the memories continued flooding back, of years here with my mother, her parents and my sister on the ground floor, while my uncle, his wife and their children lived upstairs. To the left was still the tiny kitchen with its simple stove; on the right was where we had slept on our wood-framed, woven charpai, except for my grandfather because he rose early to sell vegetables near Mochi Darwaza, one of the old city gates. There even remained the interior door on which I had been allowed to stick posters of Imran Khan, Javed Miandad and Zaheer Abbas the cricket gods who would improbably become my colleagues. Shaniera stood back a little, taking it all in, including the inch of water on the floor. Me, I could hardly wipe the smile off my face. Although I had an urban childhood, my friends jokingly call me a pendu a villager, with the tastes and the world view of the village. I like simple things, straightforward people, common courtesies.

That makes me unusual. Patronage has always mattered in Pakistani cricket. The Pakistan Cricket Board chairman is a political appointee; there is a lineage of generals, judges and senior civil servants in the role. From the Mohammads to the Niazis, our game is pervaded by dynasties. Names recur: Ahmeds and Akmals; Rajas and Ranas. In the current team, Babar Azam, Abdullah Shafique, Imam ul Haq, Usman Qadir and Azam Khan are all sons, cousins or nephews of former players.

I have no such background. I picked cricket up from watching others. The approaching sprint, the fast arms, the back foot pointing to the sightscreen they just came naturally. I went from the streets to the Test team in a couple of years despite having no link to the top and no cricket in my blood. I was still sleeping alongside my beloved, doting grandmother when I was selected, aged eighteen, to represent my country. I was praying for you my whole life, she confided. Now you will be fine. Almost forty years later, she has been proved right.

It has never, of course, been easy. Bowling fast extracts a lot from you, and I did it for twenty years. I ended up delivering more than 80,000 balls in first-class and List A cricket, and at least as many again at training. Yet cricket was never the problem. In some ways, challenging as it often was, it was the simplest part of my life. Bowling to Viv Richards, Sachin Tendulkar and Brian Lara or batting against Shane Warne, Malcolm Marshall or Muttiah Muralitharan was childs play compared to handling the expectations of my nation, the turmoil of my team and the machinations of my administration.

In Pakistan, nothing is as big as the countrys XI. Cricket was the first thing my countrymen did to a global standard, what we have been best at for longest, what has most reliably united us while also, on occasion, bitterly dividing us. Above all, it reflects us. People complain that the Pakistan team is not consistent. But the country itself is not consistent. Nothing in Pakistan happens the same way twice. On no institution can you entirely rely, and that goes right to the top: in three-quarters of a century, no Pakistani prime minister has served a full term. I played for thirteen different captains, most serving multiple terms; I had four spells in the job myself. I was under the supervision of ten national coaches and nine PCB chairmen. I recoiled from politics. But you know what they say: you might not be interested in politics, but politics is interested in you. It had a way of finding, frustrating and tormenting me; finally, as it expressed itself in the match-fixing controversies of the last decade of my career, it tainted me, and still does.

We did not have long that day in Mozang. I noticed the telltale signs of gathering commotion for a well-known person in Pakistan, twenty minutes is about as long as you can spend anywhere in public and we retraced our steps to the car. But I was ecstatic at having had my faith in my memory confirmed. It was all just as I remembered. And having seen the past light me up so, Shaniera started encouraging me to tell my story, of how the Ahmed Pura pendu had become the so-called Sultan of Swing. In all the chaos and controversies I had been part of, you see, I had kept my own counsel. I had never been sure what to do, what to say, where to begin. Suing for defamation in Pakistan is almost entirely pointless. And to head off every inaccurate story about you, particularly in the age of social media, would consume your whole life. But wasnt there a case, Shaniera said, for setting the record straight?

I had reservations. I could not claim only to be a victim. I have made some terrible mistakes. I harbour some deep regrets. And if I could not be completely frank, then there was no point, was there? So while I rush into some things, I brood on others. I got on with my life, which involved, among other things, being a good husband, and a better father to the sons, Tahmoor and Akbar, I had had with my first wife Huma, who died in 2009. Aiyla arrived at the end of 2014. She has been nothing but a joy. Now, at fifty-six, while I still suffer the diabetes that afflicted me in the second half of my career, I feel strong, secure and content.