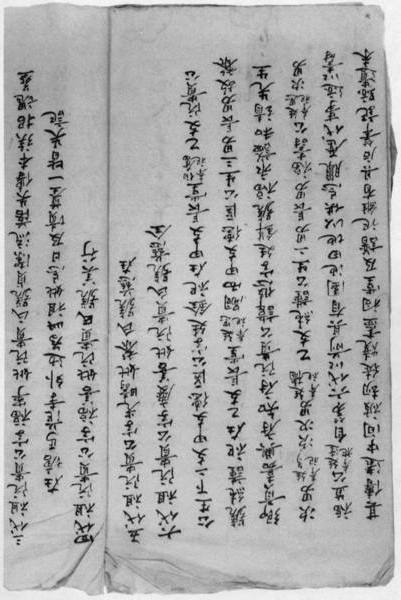

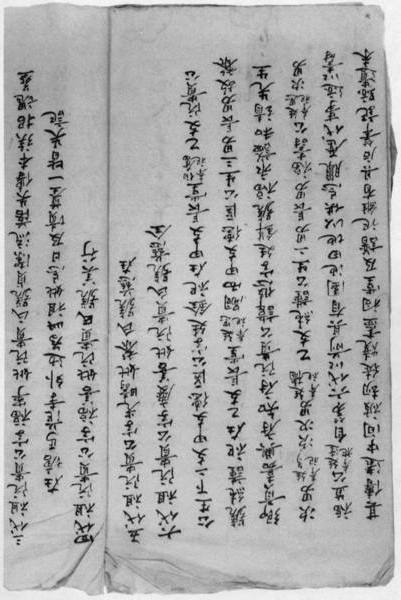

A page of the chronicle written in the scholarly-or Chinese-script by my grandfather, circa 1910. Written on absorbent rice paper, with a writing brush made of rabbit hair, the page measures 14.5cms by 29.5cms. The characters should be read from top down and right to left.

A Vietnamese Family Chronicle

Twelve Generations on the Banks of the Hat River

NGUYEN TRIEU DAN

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

This book on our village

and ancestry is dedicated to my parents.

It is written for my children

Huynh Chau, Trieu Minh, Trieu Quang and Hoang Anh,

who have grown up far away from their homeland.

My wife has been a constant source of strength.

She and the whole family have been wonderfully supportive.

This book owes much to them.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-0-7864-8779-0

1991 Nguyen Trieu Dan. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

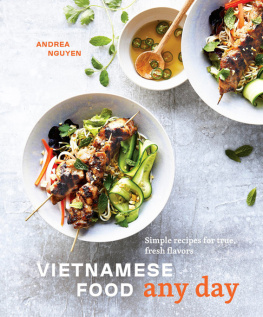

Front cover design by David K. Landis (Shake It Loose Graphics)

McFarland & Company, Inc., PublishersBox 611,

Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Prologue

Stone wears out with time.

But my heart will not forget.

The family chronicle, which we have managed to preserve through decades of war and the tragedy of exile, was compiled at the beginning of this century by my grandfather. It is being kept on the ancestors altar in our Melbourne home, in a red and black lacquer box. Written in Chinese script, the traditional way of writing for scholars at that time, it opens with the following sentences:

A tree has countless branches and a dense canopy of leaves, because its roots grow deep into the soil.

The water flows out in a multitude of streams and currents, for it has its source a long way back in the mountains.

He who inherits the merit acquired by his ancestors for many generations, has children and grandchildren in abundance.

The origins of a family are found not only in its lineage going back to the earliest ancestors in memory. They are also to be found in the land which has seen the generations succeed one another, has nourished them, and to whose fold all of us wish to return at the end of our lives. Attachment to our native land is as strong as to our kin. This is especially so for the Vietnamese who, for thousands of years, have lived in the delta of the Red River. The village and its rice fields, the river winding its way, the mountains on the horizon, have formed the setting of our lives since times immemorial. They have become part of our very soul.

This attachment to the land has been tinged with sorrow and sadness because, now as before, it has been the lot of many Vietnamese to spend their lives far from the villages where they were born.

They may have been soldiers sent to the borders, either to safeguard the country against aggression, or to take part in military campaigns to extend the national territory. They may have had to leave the overpopulated delta of the north and go south in search of new means of livelihood. It may have been, also, that the changing fortunes of war and the rise and fall of dynasties have forced those on the losing side into exile. Vietnam has had a tumultuous and violent history. During times of upheaval, which have been frequent, its peoples fate has been at the mercy of the tide of events, just as in the rainy season, the pieces of wood floating in the Red River are at the mercy of its angry current.

In the old days, to leave ones village at all meant in most instances never to return. Few soldiers who went to the borders ever came back. If not killed in battle, they rarely survived the deadly climate of those areas. Eleven generations ago, our forebears were uprooted from their village and became refugees after the dynasty they served was overthrown. They stayed away for ten years or more, before some of them were able to go back. Many of our kinsmen migrated to the south during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and all contact with them was lost. One of our ancestors visited the south as a trader, but there he died. Yet, separation from home only increased the age-old sense of belonging. The smaller the hope of return, the more desperate the yearning to do so. Homesickness has been one of the main themes of Vietnamese poetry, from folk poems communicated orally to the Story of Kieu, a long romance in verse considered as the brightest jewel of our literature. All children were taught the following folk poem in their first years of school. Impossible to translate faithfully, it nonetheless runs like this:

Last night I stood by the side of the pond.

The fish had gone deep under the water,

And the stars in the sky were dim.

Sadly I watched a spider spinning its web,

Was it waiting for a soul to befriend?

And was the Morning Star so pale,

Because of the loved one it missed?

Night after night, I dreamed of the Milky Way,

And the Polar Star of my own firmament.

Three full years have gone by.

Stone wears out with time, but my heart will not forget.

The Tao River still flows, and will ever be there.

When I learned the poem I did not quite understand the last verse, although like many other children I could recite it by heart, because the rhyme is so melodious and easy to remember. As a young man, I went abroad for my university studies. On summer nights in France when the air was warm and filled with the sounds of insects just as it was at home, I often watched the sky to look for the familiar sights of my childhood: the cloudy Milky Way which in Vietnam we call Ngan Ha or Silvery River, the stars which form the image of Emperor Than Nong, the God of Agriculture, who at harvest time would change his posture and bend over to cut the rice plants, and the bright full moon on which one could clearly see the banyan tree of the legend with Master Cuoi sleeping in its shade instead of minding his water buffaloes. But the sky in Europe was different. Stars were not at their appointed places and the moon had no banyan tree. It was only then that I understood the anonymous poet. He had to dream of his familiar sky because, where he was living at the time, it could not be seen. He was an exile crying out his love and yearning for the land of his birth.

Today, hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese are in exile. Their country is under a regime which tramples on human rights and keeps itself in power using a ruthless apparatus of oppression. In a foreign land, they struggle and toil to make a living. But the source which had nourished their spirits and their hopes is missing and the night skies of Australia, Europe and America, beautiful though they may be, are not the companions of their dreams. The English poet Coleridge wrote:

Work without hope draws nectar in a sieve,

And hope without an object cannot live.

Was he thinking of exiles like us, I wonder. For which Vietnamese has not, when evening falls on his place of refuge, felt the years slipping by him like spring water through his fingers and the waste and uselessness of his life? Yet, it is not true to say that our country-the object of our hope-has been lost. We have been separated from it, but like the Tao River in the folk poem, Vietnam is still there and it will ever be. We do not know when history will begin another chapter, but we must have faith. As in the words of the poem, let our hearts not forget. Let them not waver.

Next page