To Sara Louise;

the love of my life,

for making it all possible.

And to

Sam and Tips

for making it all worth doing.

www.JerryG.co

Many of the stories in this book relate to sections of films that have made it on to the internet. Visit Jerry Graysons website for links, more pictures and other bonus material.

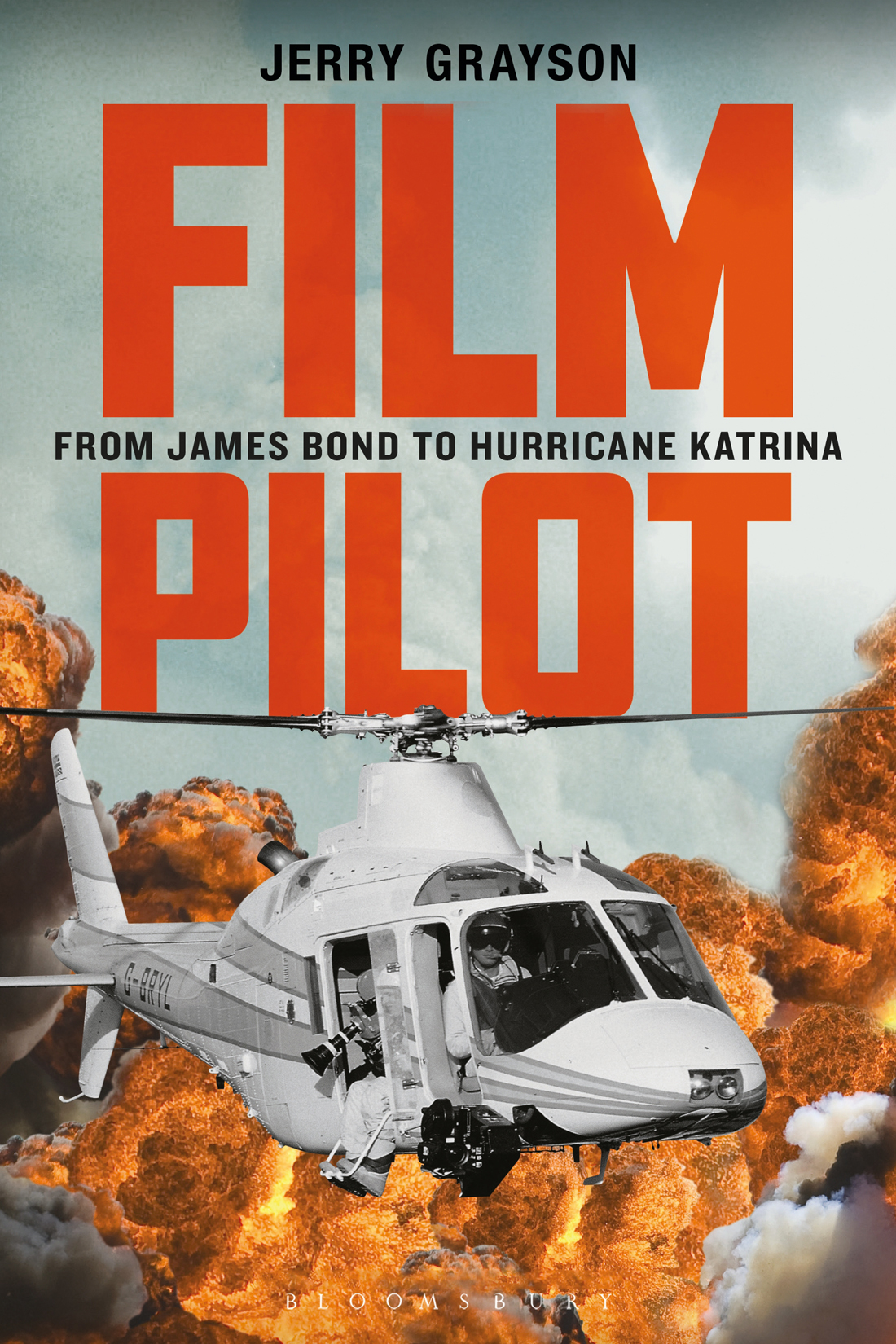

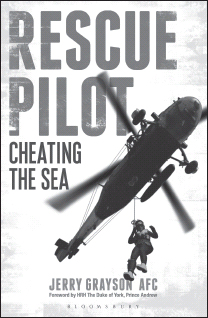

Also by Jerry Grayson, AFC

Interesting to read a different viewpoint of that tragic Fastnet Race. Graysons recollection is moving: it reads like a roll-call of terror.

Sailing Today

A grippingly clear insight into sea rescues. Fascinating.

Yachting Monthly

You will be disappointed to finish.

Australian Flying

There can be no more gripping an account of the highs and lows of life as a helicapter rescue pilot.

Pilot Magazine

Thoroughly recommended.

Fleet Air Arm Officers Association

CONTENTS

So what do you do for a living?

Around forty-five years ago I set out on a journey that would lead to me being able to answer with, Im a film pilot. The reaction so often became What does one of those do? that I soon modified my answer to I fly helicopters on movies. It serves as a good prcis and usually leads to an enthusiastic conversation about the high-profile movies Ive worked on.

However, over the years since leaving the Fleet Air Arm I slowly realised that the day-to-day job I was doing was so far outside most peoples experience that it shocked them. I was once at the engagement party of an old friend who was working in the City of London, and when a fellow guest enquired which bank I worked at I had to tell him that I wasnt with a bank, I flew helicopters on movies. He didnt come back with any response at all; he just looked quizzically at me and then turned on his heel and went to introduce himself to somebody else. I guess Id taken him too far outside his points of reference and he didnt want to deal with this strange creature whod wandered into his comfort zone.

I never found a neat answer to the question, How do you become a film pilot? Just like anybody who finds themselves in a job they love doing, there has been a bit of luck, a great deal of work and some hard knocks along the way. Most of all there has been a singularity of purpose, which meant that I was unlikely ever to be anything else.

Very few students can have experienced the sort of transformation I went through after a visit to the school assembly hall by a good-looking guy in overalls. Hed left the school himself only a few years earlier and was now returning, in what turned out to be flying overalls, as the holder of the Daily Mail prize for their Transatlantic Air Race of 1969. It had been a race that captured the imagination of the nation and made front-page news long before the internet was even thought of. In fact, we had only just installed a black and white television to watch Neil and Buzz walk on the Moon that same year. The swinging sixties had brought Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithful to the steps of our local court house in Chichester, a quiet cathedral town on the south coast of Britain, but I had been too young to understand that the world was rapidly changing.

The Transatlantic Air Race was all about getting a person from the top of the Empire State Building in New York to the top of Londons Post Office Tower in the shortest time possible. On the day, Lieutenant Commander Brian Davies AFC RN delivered his observer (the Navys term for a navigator) Peter Goddard in a time that trounced the RAF by exactly one hour. So it was that Brian made his triumphant way back to Chichester High School for Boys to tell us the story of his race. And so it was that I found myself sitting in the school hall that day asking myself, in incredulity, Thats a job ?!

The concept of being paid to fly a machine captured my attention instantaneously. I now had a reason to concentrate in the classes on Maths, Physics and Geography. I was motivated with a capital M. I was too tall and gangly to ever have a shot at the cutest girls so distractions were minimal as I focused on becoming an aviator; a task I succeeded at in the month of my seventeenth birthday. Very shortly thereafter I became the youngest pilot to be accepted into the Fleet Air Arm. Along the journey to that moment I had nearly lost my way by assuming Id be better off as an airline pilot, but the closure of the British Airways school for pilots and a kindly careers master had set me back on track.

The next eight years were rich, rewarding and most of all fun, starting with learning which uniform to wear for each occasion, which people to salute and which to expect a salute from. We went to sea in huge aircraft carriers, chased Soviet submarines in Sea King helicopters and relaxed in the fleshpots of exotic European and American ports with sophisticated young ladies whose parents were only too glad to see their daughters on the arm of a British naval officer.

By the age of twenty-five I was a highly decorated veteran on the Wessex helicopter type that had carried Pete Goddard from Brians Phantom to the Post Office Tower. Its a measure of my enjoyment of those eight years, and particularly of my time flying on Search and Rescue duties, that they warranted a book of their own: Rescue Pilot Cheating The Sea.

Its often said that a man spends his time in the military feeling like a civilian in uniform and the remainder of his life feeling like a military man in civvies. Thats pretty much how its felt for me except that civvies for a helicopter pilot generally still involves uniform, usually with the four rings that denote the same qualifications as an airline captain.

In all other aspects the process of becoming a civilian was a strange and alien task. No longer did daily orders dictate where I should be and at what time; this was now something I had to work out for myself. It was a transition that many of my contemporaries had avoided in favour of joining either Bristows or Bonds, the two big helicopter companies that fed oil-rig workers out to the North Sea. In those companies, as I heard from time to time, the pilots were still subject to some form of daily orders, with a few differences, such as having a union representative to run to in times of grievance, plus the probability that they would return to sleep in their own beds at the end of their working shift. For the flying part of the job these guys were still working in conditions just as hairy as wed experienced in the Fleet Air Arm, but with the added responsibility of carrying a full set of passengers who had not signed up to experience daring feats of aviation.

In the sleepy south-west of England my old mate Keith Thompson and I set about establishing a small helicopter charter company under the benign patronage of Roy Flood, a wonderful character who had the reputation of being one of the most successful used-car dealers in the country. You couldnt run a successful business in an area of such sparse population without having a loyal clientele, and that was the first of many good lessons I learned from Roy over the years. Since Roys car dealership was called Castle Motors we named our new aviation enterprise Castle Air.