Memoirs are by definition a written depiction of events in a persons life. They are memories. All of the events in this story are as accurate and truthful as possible. Many names have been changed to protect the privacy of others. Mistakes, if any, are caused solely by the passage of time.

Copyright 2014 by John R. Nutting

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by David Sankey

Cover photo credit Steven Stafford

Print ISBN: 978-1-62914-424-5

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62914-912-7

Printed in the United States of America

Editors Note

The Court-Martial of Corporal Nutting features selections of trial transcripts and letters written by Nutting when nineteen years old. These have been left unedited and contain the original misspellings and grammar. This serves to illustrate the urgency and lack of resources as experienced by a soldier on the front. There are many mistakes. This is part of the message.

When I first began writing these pages, it was November 15, 2007forty-one years ago to the day that I arrived in Vietnam. I finally have the courage to tell this story to my children, for them to pass on to their children and beyond before it ceases to exist with my passing.

Foreword

I never met Corporal Nutting in Vietnam, although I am sure at one time or another we were only a few feet apart. He probably sat in the back of my H-53 chopper as we pulled the marines units out of landing zones along the string of outpoststhe McNamara Linejust south of the DMZ. Con Tien, Gio Linh, and the rock pile were strung out along the line a few miles north of Dong Ha, the last airfield and a piece of near civilization, below the DMZ.

We hauled food, ammo, and medical supplies into the LZs from the Dong Ha LSA (Landing Support Activity) and body bags out to graves registration in Danang.

I was lucky one day when I needed some home services done in my hometown and called Mr. Nutting, who ran his own business, Top Hat Chimney Sweep. We talked several times and got to know one another.

This book is actually two books in one. The combat book is a real page-turner and one of the best I have ever read that truly defines combat action as seen through the eyes of a young marine who lived through the worst of it.

The second book is a sad tale of what it was like stateside waiting to be released from active duty. The military of that time was preoccupied with the War on Drugs.

It seems unbelievable today, forty years later, that we spent so much time and effort trying to convict a combat veteran who had given so much to his country over one marijuana cigarette. We came so close to doing an unbelievable injustice.

The second book is an expos of our time and should be digested. Somehow, we pushed back from the brink and did not destroy a combat marines life.

Ray M Franklin, Major General, USMC (Ret.)

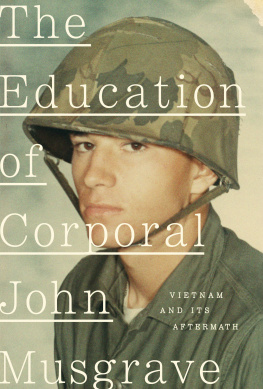

A lmost forty-eight years ago, I stepped into a whole new world. The air was different. It was stifling, heavyone of those brief periods of sunshine during the monsoon. The red mud was thick and stuck to our stateside boots. Phantom jets rattled our core while we strained to hear some sergeant giving us orders to form up and wait for our gear. Maybe what I remember most from that first day is how a company of marines looked when disembarking from the helicopters.

They were coming back from a mission, and they looked differentdifferent from us. Not because they were grungy and wearing combat gearit was how they looked if your glance caught their eyes. We were a whole planeload of FNGs, and they were combat marines who had just gone through some kind of hell. Even though we all were about the same age, they looked in a strange way like they were much older.

Staging in Danang, Vietnam, took a couple of days. We got our shots, received our rifles and web gearall the things we needed to go into combat.

My new orders came down to proceed to 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marine Division. I climbed into a 4x4 for the trip north. Eight other marines clambered in with me. We rode in the back of the open truck to the Marines Camp Carroll near the border with North Vietnam. This was the day before Thanksgiving, 1966.

On arrival, I reported to weapons platoon Foxtrot Company, which was about ten miles from Camp Carroll. F Company was stationed around what the marines called the big tit, a small mountain about one mile south of the demilitarized zone (DMZ). I thought this peak rising above the jungle flatlands looked more like a big tooth jutting out of the jungle than a tit because of its steep sides. Our company occupied bunkers that were somewhat evenly spaced around the entire circumference at the base of the big tit. In front of the bunkers, facing the jungle was a tangle of concertina wire and claymore mines.

By the time I slogged my way around inside the maze of wire, and finally checked in with my squad, I was really sick, as sick as I could ever remember. I had cramps that would practically double me over, explosive diarrhea, and hot and cold chills. This caused my teeth to rattle.

Once I found my bunker, I crawled up on a sandbag ledge and listened to rats fighting inside the walls. I watched flooding from the torrential monsoon rains cover the bunker floor. I hoped I could fight off the cramps until nightfall. If you had to take a crap during the daylight, some unlucky marine had to go with you through the concertina wire, past the claymore mines, and then stand guard while you dug a quick slit trench and did your business. Nobody wanted to die standing guard over the FNG with the screaming eagle shits. I heard one of the old salts say that although everyone gets the screaming eagles when they first get here, I had it pretty bad.

Corporal Morris Franklin Dixon escorted mereluctantlyout beyond the wire late in the afternoon, when I could no longer hold back the cramps. I remember Dixon to be an intelligent, thoughtful individual who was married and had a little girl. For some reason he didnt share with anyone at the time he had dropped out of medical school and joined the Marine Corps. Dixon was a kind soul when I needed one.

Several months later I heard he was killed somewhere near Quang Tri.

As we worked our way through the wire back to the bunker, Dixon explained to me that I really did need to hold it until after dark if I could. During the night a marine could work his way up the steep trail, groping his way along in the dark, until he felt the box; then he could have the luxury of a real sit-downinside the concertina wire. Marines had earlier constructed a very crude toilet: a hole had been cut in a discarded wooden artillery-shell crate and placed over an old foxhole dug on the peaks summit. Dixon pointed to paths behind each bunker disappearing into the brush and winding their ways to the top of the big tit.