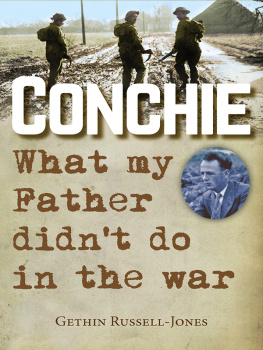

CONCHIE

What my father didnt do in the war

GETHIN RUSSELL-JONES

Text copyright 2016 Gethin Russell-Jones

This edition copyright 2016 Lion Hudson

The right of Gethin Russell-Jones to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Published by Lion Books

an imprint of

Lion Hudson plc

Wilkinson House, Jordan Hill Road,

Oxford OX2 8DR, England

www.lionhudson.com/lion

ISBN 978 0 7459 6854 4

e-ISBN 978 0 7459 6855 1

First edition 2016

Acknowledgments

Extracts from The Authorized (King James) Version. Rights in the Authorized Version are vested in the Crown. Reproduced by permission of the Crowns patentee, Cambridge University Press.

Scripture quotations marked NIV taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version Anglicised. Copyright 1979, 1984, 2011 Biblica, formerly International Bible Society. Used by permission of Hodder & Stoughton Ltd, an Hachette UK company. All rights reserved. NIV is a registered trademark of Biblica. UK trademark number 1448790.

Cover image Mirrorpix

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Contents

Mummy and Daddy you fought the good fight, finished the race and and kept the faith. May you rest in peace and rise in glory.

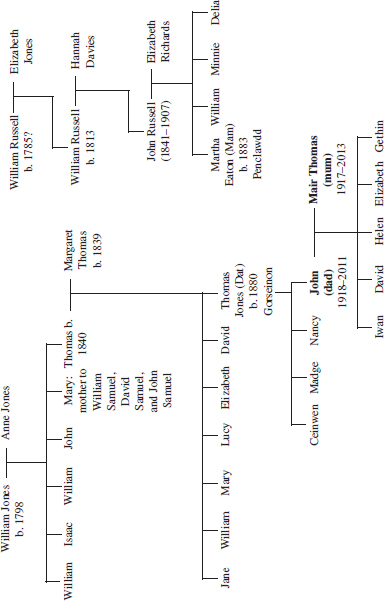

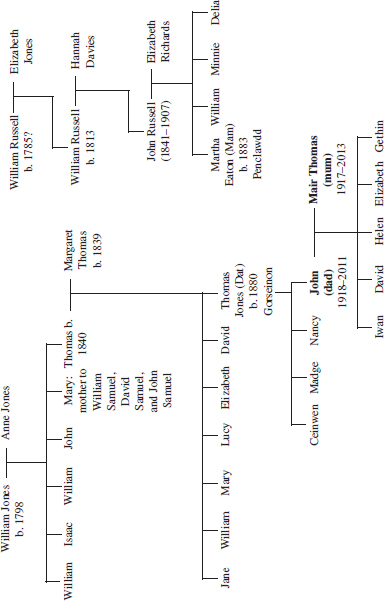

Family Tree

C HAPTER 1

War Child

To kill Germans is a divine service in the fullest sense of the word.

Archdeacon Basil Wilberforce, Chaplain to the Speaker of the House of Commons (1914)

We are on the side of Christianity against anti-Christ. We are on the side of the New Testament which respects the weak, and honours treaties, and dies for its friends and looks upon war as a regrettable necessity It is a Holy War, and to fight in a Holy War is an honour.

Right Reverend A. F. Winnington-Ingram, Bishop of London (1914)

Christ would have spat in your face.

Anglican chaplains words to an imprisoned conscientious objector during World War One (1917)

But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.

Jesus of Nazareth

This is what conscience looks like. Its a fourteen-year-old boy sitting anxiously on a sofa late in the afternoon. Hes fondling a bloodstained tissue as his parents look at the purple swelling around his right eye. A knock on the front door and in comes his grammar school form teacher and out comes the story. My brother Iwan had been playing football that lunchtime, during which he had been assaulted by the school bully, who for no explicable reason punched him several times in the face. To the consternation of everyone, Iwan had not retaliated and had walked away with a bloodied nose and mouth. None of his friends understood his reaction and neither apparently had his teacher. So this was his question to my brother: Iwan, why didnt you fight back? You were entitled to defend yourself. This question has been bothering me since school ended and I had to ask you. Iwan, who has never been a timid soul, had a clear and surprising answer. It was the way I was brought up, sir, never to take revenge on anyone. It would have gone against my conscience.

This book is about the power of conscience and the way it influenced my familys story. In particular its about my fathers life before, during, and after World War Two. Im going to tell the stories of the people, events, and ideas that shaped a decision he took as a 21-year-old man; a decision that still reaches into his family years after his death.

Most of us over the age of fifty have a war story. In one way or another, our fathers and some of our mothers were involved in the Second World War, willingly or not. And whether alive or dead our grandfathers also gave report of life and death in the First World War, the Great War. Beneath the largely peaceable skies of the northern hemisphere, we are only one generation removed from events that rocked the world and shaped the culture we inhabit.

Take my friend Dave for example. As we sit sipping coffee and he munches on a teacake, he asks me about this book. I explain its about pacifism during World War Two. He then discloses two extraordinary war tales. His father, Ron Clague, was one of the first to liberate Dachau, whose infamy as a Nazi death camp has gone down in history. Such was the disfiguring and deadly evil witnessed by this twenty-year-old, that he barely spoke about it. Dave talked also about Rons best friend, Ernie. As a teenager, Dave casually asked Ernie what he had done in the war and he received a reply that had never been given until that moment. Holding back tears and trying to contain big, painful emotions, Ernie talked about the Death Railway, made famous in the films The Bridge on the River Kwai and The Railway Man . Captured as a prisoner of war by the Japanese, he was forced to work on the vast railway that stretched from Ban Pong in Thailand to Thanbyuzayat in Myanmar (Burma). It was a brutal and torturous regime and many POWs were beaten to death. There were also a huge number of deaths among the Romusha, Asian civilians forced to work on the railroad. Over 12,000 British, Allied, and American servicemen alone lost their lives. It is said that for every piece of track laid, someone died.

A few days later and I am having coffee with Martin, another friend. In the course of our conversation, I casually mention the subject of this book and he drops a bombshell. His grandfather Maurice Allen was a conscientious objector (CO) in the First World War, whilst his father Dennis was a CO in the Second.

I too have a story; Im just not sure whether I like it that much.

My dad, John Russell-Jones, was a CO (or Conchie as they were usually called) in World War Two. I want to open the sealed envelope of my fathers account, get behind the story, and find the 21-year-old young man who was prepared to face such opposition. This quest is given added bite by the looming centenary of an Act of Parliament that made my fathers dissent, and that of many thousands like him, possible.