Contents

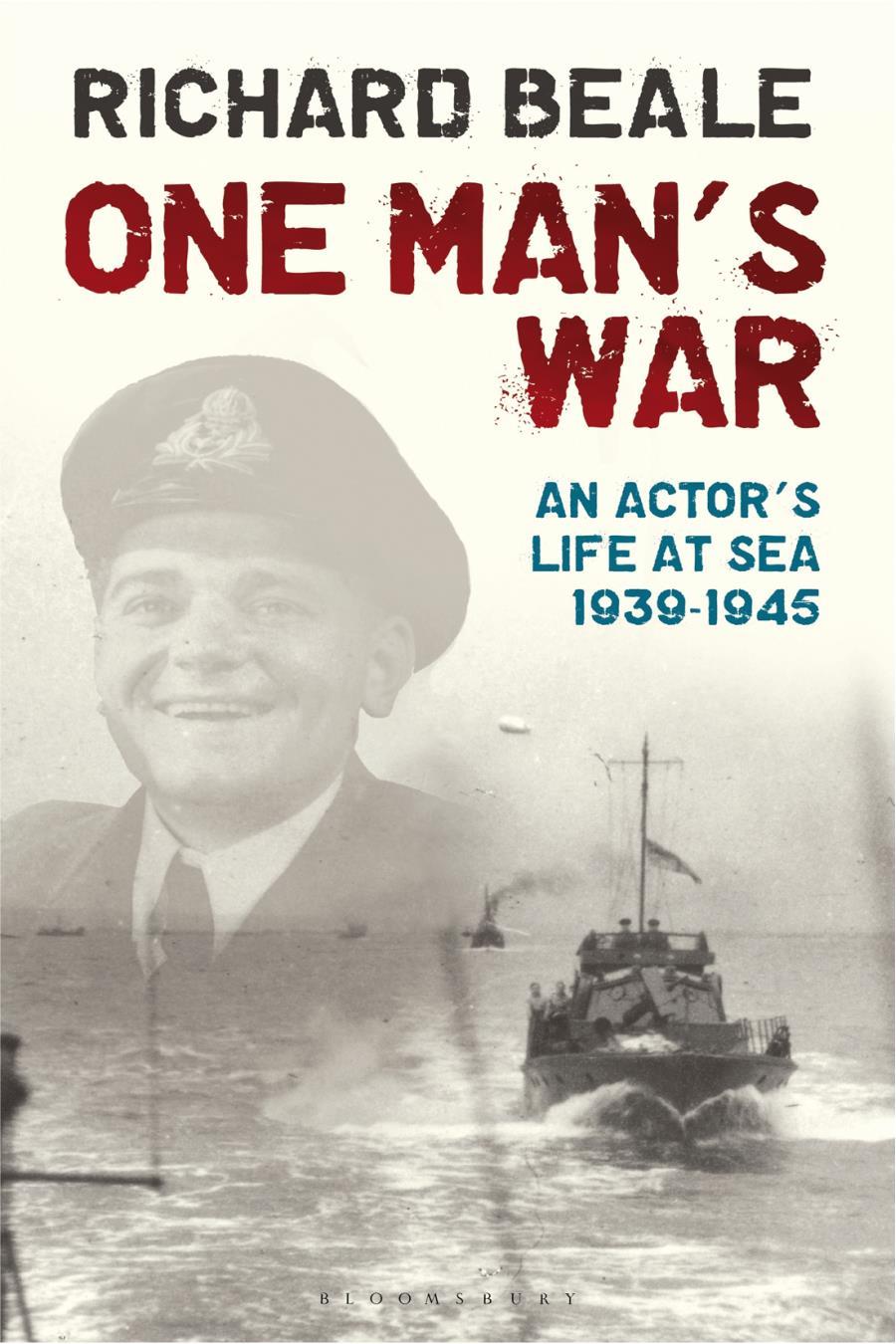

People write books for various reasons, some for fame, some for money, some for solace and many for a mixture of all three. I wrote One Mans War out of a feeling of indignation!

One morning in the early spring of 2014, I became aware of something missing in my life. For forty-two years as an actor I had read and learned other peoples words. Was it not time to set down a few words of my own, for better or for worse?

The thought tapped at the door of my consciousness for several weeks until it opened, and the decision was made.

What was to be the subject? The theatre was rejected as being over-published already. Sailing, and life in post-war Britain, also seemed inadequate and I doubted my ability to make them interesting. That left the war. Here was a ready-made series of events that only needed recall.

The first pages were written in a bed and breakfast establishment, an ideal place for the task as it held no distractions, and was sufficiently boring to keep my mind on the job.

By the time I returned to my newly decorated cottage enough momentum had been gathered to continue the process. Events unfurled in my memory like a roll of film, and the book began to write itself.

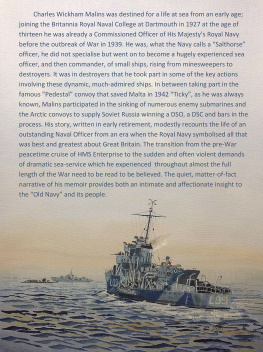

One Mans War became a day-by-day account of one mans part in the 193945 war against Hitler. The action ranges over the North Sea, the Western Approaches and, to a greater extent, the Mediterranean and the Adriatic.

In the early chapters and at the end I have tried to give glimpses of England at the time, and of home life when on leave.

Apart from the outset, I have omitted many references to the calendar, although I must have been aware of dates when writing up the log. Events became part of a continuum in which happenings led from one to the next in a chain, ending in the cessation of hostilities in 1945.

I particularly thank Roger Kirkham for carrying out the arduous task of typing my hand-written manuscript and transferring it to a CD. Very special thanks to my daughter Anya for all her help and encouragement.

One Mans War is dedicated to the memory of all who died that we may live, and to the memory of my two brothers who also served at sea.

194041

Stand in line. No talking!

Having delivered this ultimatum, the Petty Officer retired to his corner and renewed his acquaintance with a mug of tea and half a pork pie.

My war started in Finchley, which is a bit like saying the earthquake started next door. To be precise, it began in the Territorial Army Drill Hall in Finchley. It was late spring 1940 and unusually hot. A long queue of callow young men stretched the full length of the hall. Each had a rather pathetic-looking cardboard box hanging around his neck by a piece of string, which contained the civilian gas mask. Somehow the box and the string added to the callowness of the scene.

A strong smell of sweat, backed by a faint odour of carbolic, hung in the air like a cobweb. The front of the line faced a blank wall with a door near the centre. From time to time this door would open and a uniformed figure would emerge and beckon to the young man at the front of the queue to enter.

Eventually my turn came. I went through the door to be faced by a long table behind which sat a three-ring Royal Navy (RN) Commander, flanked by a Lieutenant Commander and a Lieutenant. I was questioned about my family, my friends, my hobbies, my school, what books I had read and my favoured sports until at last, the thousand dollar question was put to me by the senior officer. He raised his eyes until they were level with mine and, looking hard at me, asked quietly,

Why do you wish to join the navy?

I was unprepared for this, and thought wildly of various answers. Should I spout some rubbish about love of the sea, about admiring the Senior Service, or invent some nautical family connections? No, because I was basically a truthful young man of nineteen and, after what seemed like five minutes, said, Well, sir, if I have to die I would rather die at sea than in a trench.

Thats torn it, I thought. Thats the end of that. Ill be told to go home and wait to be called up by the army. It was at the time of the so-called Phoney War and as yet no one had felt the effects of hostilities. Maybe I would never be called. I waited while their heads came together and conferred in private. At last the commander turned to me and said, Subject to a satisfactory medical you will be accepted. Then the floor gave way beneath me, and a hundred days of hopes and dreams came flooding to life.

Thank you, sir, I will do my best, I said.

Thats all we ask, proceed, he replied, and he pointed to one of two doors, one leading to a temporary sick bay, and the other to the outside world.

The sick bay walls were decorated with posters bearing cheerful messages about disease, mostly of the venereal kind. There was some rudimentary equipment and a nurse. My pulse was taken, my height measured, my chest and heart were sounded and then finally a sample of urine was required. I was given a small hospital bottle, but, on account of the three hours I had been in the building, this container proved most inadequate. The bottle filled too rapidly, and I was rushed over to a sink to complete the operation. The nurse giggled. This was an unpromising start to my naval career. I was then taken to an annex housing a desk, two filing cabinets and a Chief Petty Officer who was having his tea. He put aside a ham sandwich, gulped down the last of his mug, and commenced a long recitation designed to give the new boy some idea of what to expect in the weeks to come. The gist of which was that I was to return home to wait for further instructions. I was also not to go abroad, or leave my present address, engage in careless talk, or give up my job before receiving a call-up notice.

Six weeks later I received instructions to report to HMS Collingwood at Fareham, in Hampshire; a rail warrant was enclosed. Goodbyes were said, tearfully in the case of my Mother and manfully by my Father. We shook hands and he wished me luck. Men did not embrace in those days. Then came a surprise: my two younger brothers, who were still at school, presented me with a magnificent dressing case in soft calf leather bearing a label inscribed Swain & Adney, Park Lane, London. They had sold their most treasured possession, an electric train set, which had been built up over the years and covered the loft floor. It was hard to remain calm and in control in the face of such generosity.

HMS Collingwood proved to be a large training camp, consisting of some twenty huts surrounding a parade ground. Each hut housed twenty-four trainees. The hut was lined with twelve double bunks, six on each side. Life in the camp was in the main uneventful, if not to say boring. We drilled, learned to sail a cutter, learned to row whalers which are the lifeboats carried in the waists of cruisers and larger vessels we were taught sailors knots and splices, with each followed by more drilling on the parade ground.

The food there was reasonable. But it was said that the tea and cocoa were laced with some stuff called Rumoy which was supposed to inhibit sexual desire. There was a good NAAFI (Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes facility) where you could supplement the diet with bacon and beans, and buy Cadbury quarter-pound chocolate bars for tuppence a time.