Contents

Page List

Guide

Gullah Days

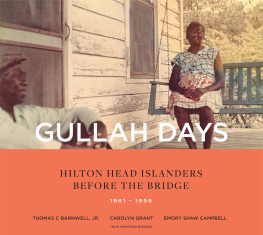

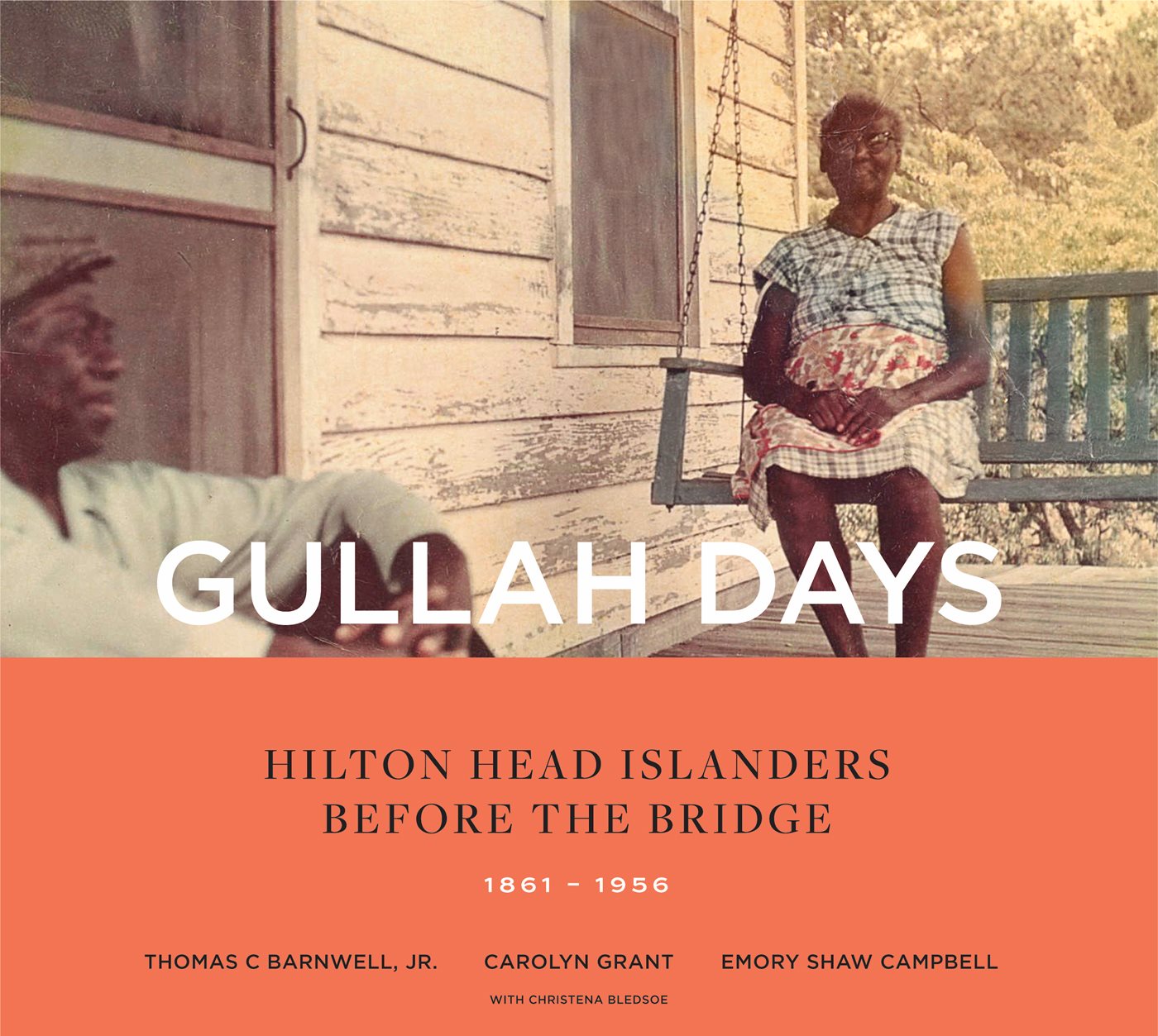

GULLAH DAYS

Hilton Head Islanders before the Bridge, 18611956

THOMAS C. BARNWELL, JR. | EMORY SHAW CAMPBELL | CAROLYN GRANT with CHRISTENA BLEDSOE

Copyright 2020 by Thomas C. Barnwell, Jr., Emory Shaw Campbell, and Carolyn Grant

All rights reserved

Printed in South Korea

Cover design by Hannah Lee

Interior design by April Leidig

Blair is an imprint of Carolina Wren Press.

The mission of Blair/Carolina Wren Press is to seek out, nurture, and promote literary work by new and underrepresented writers.

We gratefully acknowledge the ongoing support of general operations by the Durham Arts Councils Annual Arts Fund and the N.C. Arts Council, a division of the Department of Natural & Cultural Resources, and from Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

ISBN: 978-1-94946-707-9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019941193

FRONTIS: Young women with horse and wagon, boy looks on, Hilton Head, SC, 1904. American Museum of Natural History, Library: Julian Dimock Collection

ABOUT THE COVER PHOTO

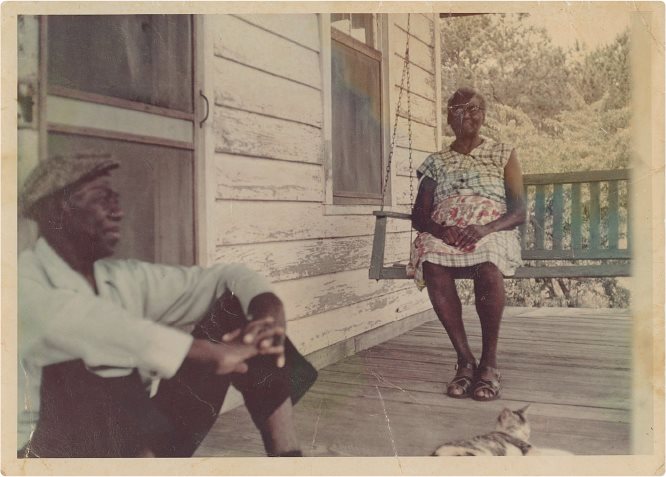

Hilton Head Island Gullah Islanders Perry and Rosa Williams Enjoying the Summer Breeze, Circa 1960

Photo courtesy of their grandchildren

As they sat on their porch one summer afternoon in the 1960s, a curious passerby caught a glimpse of Perry and Rosa Williams, Gullah residents of Hilton Head Island and the maternal grandfather and grandmother of book author Emory Campbell. With their permission, the passerby took a picture of the Williamses sitting on the porch of their home off of Bryant Road in Spanish Wells, one of the many Gullah communities on the island. As homes at that time didnt have air-conditioning, the Williamses were relaxing on their porch to catch the fresh air circulated by the summer breeze. A few years earlier in 1956, the bridge had opened connecting Hilton Head Island to the mainland. Many people had arrived on the island. They took pictures, explored the island for artifacts, and offered to buy marsh tacky horses and wares from Gullah islanders who would be willing to sell them. Home on vacation after having migrated north, Emory stopped by to visit his grandparents. They showed him the picture and told him a buckra (a term Gullah people used to describe Caucasian persons) woman had stopped by their home and took the picture of them. In the Gullah community it was rare for people to have their pictures taken, and if they did, they wanted to be well dressed. Emory was surprised his grandparents allowed a stranger to take their picture, especially since they didnt know what she was going to do with the picture. He expressed his dismay. Despite that, the picture is treasured by Emory and his family as it is the only photo they have of their grandparents sitting together.

With great pride and love, we dedicate this book to our families and the Gullah families of Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. Thank you for your love, support, and patience.

Thomas C. Barnwell, Jr.

Emory Shaw Campbell

Carolyn Grant

Emory Campbells paternal grandparents, Perry and Rosa Williams. Picture taken on the veranda of their home in the Spanish Wells neighborhood, Hilton Head Island, in the 1960s. Perry was a WWI veteran, retired U.S. Corps of Engineers dredge hand, and fish net knitter; Rosa was an expert fisher and homemaker. Collection of Emory S. Campbell

Contents

PART I. GULLAH HISTORY BEFORE THE BRIDGE

Planting watermelons, Hilton Head, 1904. American Museum of Natural History, Library: Julian Dimock Collection

Chapter One

FREEDOMS DOOR

N O CLOUDS DARKENED THE SKY, no winds whipped the sea, yet thunder shook Hilton Head Island on November 7, 1861. Or so it seemed.

On nearby Ladys Island, a young boy listened in wonder to what sounded like rolling thunder on a calm day.

Son, dat aint no tunder, his mother told him in her lilting African speech, dat yankee come to gib you Freedom.

The Day of the Big Gun Shoot had begun.

The roar of heavy guns resounded throughout the low-lying Sea Islands of South Carolina, carrying as far south as Fernandina, Florida, seventy miles away. To the young boy and thousands of other enslaved people within earshot, the gun roar heralded freedom. It was as if Moses had leapt straight from the pages of the Bible to part the Red Sea againthis time to lead the children of Africa out of bondage.

Seven months earlier, in April, Confederate batteries fired on Fort Sumter in the Charleston Harbor, triggering the Civil War. Within three days, President Abraham Lincoln ordered an extensive blockade of the southern coast in order to cut off Confederate commerce and thus much of the Confederacys wealth.

In July, planters on Hilton Head and neighboring islands sent their slaves to build two earthwork forts to guard the entrance to Port Royal Sound: Fort Walker on Hilton Head and Fort Beauregard at Bay Point on Phillips Island, located directly across from Hilton Head. As enslaved people built steep earth banks, cut palmetto logs for ramparts, erected powder magazines, and constructed gun emplacements, excitement seized them. Anticipating the end of slavery and slave rations, they made up a rhythmic work song:

No more peck of corn for me, no mo, no mo

No more pint of salt, no mo, no mo

No more drivers lash, no mo, no mo

No more mistress call, no mo, no mo.

With each drive of an axe into a palmetto log or shove of a log into the earthwork embankment, the men sang in unison: no mo (no more).

It was an upbeat song. They were hopeful.

Masters and slaves on Hilton Head and other islands had been on constant alert ever since those hot summer days. Masters feared the Union might invade. Slaves knew if the Union soldiers came, they would come to free them.

The day before the battle, headlines in the New York Times announced that South Carolinas Port Royal Sound appeared to be the likely site of a major battle.

For three weeks Northern readers had followed avidly news reports of a great Union fleet sailing south to wage war at an undisclosed location. When the colossal joint navyarmy expedition reached, and passed, Charlestonthe birthplace of secession, the