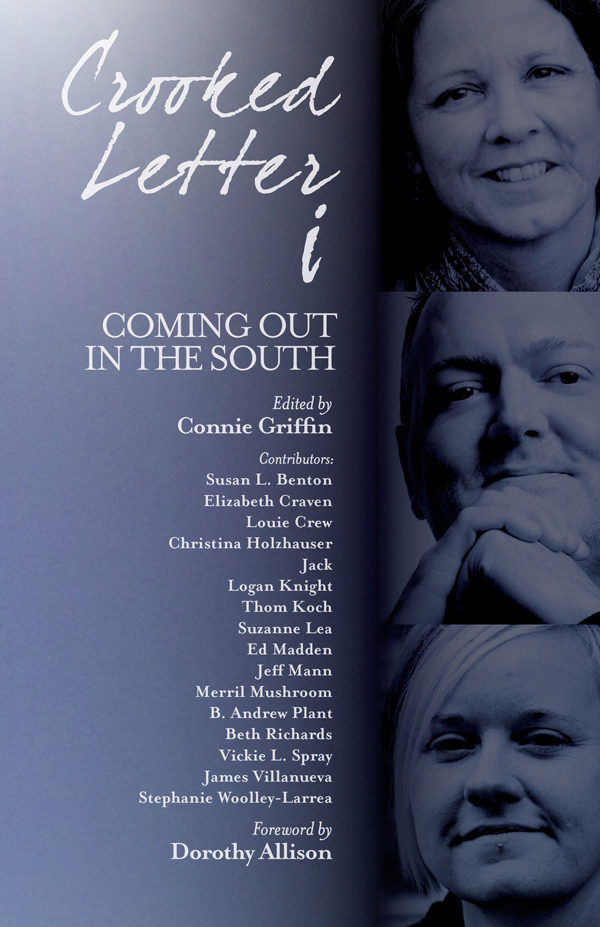

Crooked Letter i

Coming Out in the South

Connie Griffin, editor

Foreword by Dorothy Allison

Contributors

Susan L. Benton, Elizabeth Craven, Louie Crew, Christina Holzhauser, Jack, Logan Knight, Thom Koch, Suzanne Lea, Ed Madden, Jeff Mann, Merril Mushroom, B. Andrew Plant, Beth Richards, Vickie L. Spray, James Villanueva, Stephanie Woolley-Larrea

N EW S OUTH B OOKS

Montgomery

NewSouth Books

105 S. Court Street

Montgomery, AL 36104

Copyright 2015 by Connie Griffin. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by NewSouth Books, a division of NewSouth, Inc., Montgomery, Alabama.

ISBN: 978-1-58838-313-6

eBook ISBN: 978-1-60306-362-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015948356

Visit www.newsouthbooks.com

Acknowledgment of Permissions

Grateful acknowledgment is expressed to the following for permission to publish: Southern (LGBT) Living first appeared in Binding the God: Ursine Essays from the Mountain South (2010) and is reprinted with permission from Bear Bones Books/Lethe Press. An earlier version of Calling was published in The Emergence of Man into the 21st Century , a collection of essays about masculinity, edited by Patricia Munhall, Ed Madden, and Virginia Fitzsimons (Jones & Bartlett with the National League of Nursing, 2002).

All images courtesy of the authors except as otherwise listed: Susan Benton (Linda J. Nelson; B. Docktor), Connie Griffin (Shurong Wang), Christina Holzhauser (current, Ralph Horne), Ed Madden (current, Forrest Clonts), Jeff Mann (current, John D. Ross), B. Andrew Plant (current, Robin Henson), Vickie L. Spray (current, Sahra Humes), Stephanie Woolley-Larrea (Amy Duffing).

How do you spell Mississippi?

M - i - crooked letter - crooked letter - i

crooked letter - crooked letter - i

humpback - humpback - i.

And thats how you spell Mississippi!

Contents

Foreword

Dorothy Allison

When I was a girl I understood that my life, my true life, what I really thought about, dreamed and hoped forall that was a secret, indeed had to be a secret. I feared most of all losing my mothers love, or of shaming her, or even adding to the difficulty of her life by telling her something that would frighten her or make her see me as more endangered than I was.

The larger world outside my somewhat embattled family was another thing altogether. I feared it, of course. I knew that my family in particular was held in contempt for being poor, disreputable, and minorly famous for uncles who occasionally went to jail but more frequently simply engaged in acts of public drunkenness or sudden unexplained violencemostly visited on other members of my family. Then there were all my female cousins and aunts notorious for invariably arriving at their own weddings with bellies swollen with the babies that would arrive shortly after their minimal honeymoons. We were the disreputable poor, rednecks with bad attitude, crooked by definition, outlaws by declaration. Even I, the high-achieving good student hid a caustic attitude behind my relatively respectable demeanor. But that was a secret like almost everything important about me.

When I was twenty, away at college full of hope and terror, I confronted the fact that if I revealed too much about my real life, my stepfathers sexual and physical abuse, or my deep attraction to other young women, I could lose the life I was trying to build. I could be cast outliterally expelled from college or sent off to a mental institution. I had seen another young woman, a gender outcast who so far as I could tell was not really a lesbian, but dressed like one and was in continual revolt against the gender expectations for young women at our nominally Presbyterian private college. Her family appeared in the middle of the night to arrange to have her taken away by force to a facility where, it was expected, she would be fixed.

How would she be fixed? I dreaded the answer to that question and learned with great terror that she had been subjected to electric shock therapy, insulin injections, and continual meetings with determined therapists who led her to renounce all she had been and become what the family wanted her to be. She reappeared a year later, a shadow of whom she had been, head down and hands trembling. She had been vibrant, outspoken, whip-smart, and fearless. This new version of that girl was none of those things and she did not remain long in the dorm, disappearing on another terrible night after trying to take her own life.

I remember thinking that it was all terrible. I left my dorm and climbed up on the roof of the library. I stayed up there all night worrying and grieving. I had barely known that girl but I had known her all too wellher anger and her hopes.

She thought her life was her own.

I had never truly believed that. I had always known I was in some terrible way propertythat I belonged to my family in both wonderful ways and terrible ones. My mothers hopes and dreams for me were as heavy as my stepfathers contempt and lust. I was the one who escaped, but who really escapes? Would someone come for me in the night? Would my tentative feminism and carefully concealed lesbian desires doom me before I had done anything I hoped to do?

In this new wondrous age with Supreme Court decisions affirming gay and lesbian marriages, and gender being redefined as nowhere near as rigid as it has previously been defined, I sometimes wonder if anyone knows what our lives were like at the time when I was a young woman, trying to figure out how to live my life honestly in the face of so much hatred and danger. Who are we if we cannot speak truthfully about our lives?

How did we come to this new age in which we can take our lovers home or to church or walk hand in hand down the street without lies or pretense or a carefully crafted fictional stance to protect us?

Speaking truth to power was a tenet of the early womens movement. We would change the world by the simple act of declaring our truth and refusing to back down or lie no matter how virulent the response.

How virulent was the response? Take a look at some of the essays in this book and you will see. But more importantly, you will see the internal evolution of people who wanted simply to be themselves. It was not easy or simple or even a matter of confronting prejudice. Most of these peoples deepest struggles were with themselves, their families, and their faith, their most personal convictions.

Confronting the enforced silence of manners and social expectations, we claimed our lives for ourselves. Was it heroic? Was it audacious, marvelous, scary and day by day painful? Of course. Did we change the world? Look around you and marvel.

Dorothy Allison grew up in Greenville, South Carolina. Her novel Bastard Out of Carolina (1992), which became a national bestseller, was a finalist for the National Book Award.

Introduction

Connie Griffin

The title of this collection, Crooked Letter i , derives from the chant that many Southerners will recall learning as youngsters as an aid to spelling that most difficult of states, Mississippi. Like the Sthe crooked letterwe were considered the crooked ones in our families, schools, churches, and communities. We believe that having survived as outsiders entitles us to take back the chant, as we have taken back so many other epithets thrown our way over the years. Having earned the right to embrace our crookedness, we celebrate itno straightening out needed!

Crooked Letter i: Coming Out in the South is a collection of first-person narratives by lesbian, gay, transgender, and queer-identified individuals who grew up and came out in the South. (I also sought submissions addressing bisexual Southern lives, but unfortunately received none. And I am saddened that the only account from an African American perspective is Louie Crews piece, telling the story of his partner, Ernest Clay.) The experiences represented here pivot around a central themefinally finding language to express unnamed feelings, and then discovering, contrary to what we had always thought, we were never the only ones. Revealing a vibrant cross-section of Southerners, the writers of these narratives have in common the experience of being Southern and different, but determined against all odds.