CONTENTS

There are a number of people who have contributed to this book being brought to fruition and I should like to thank them here:

Mum, Christine, Barry, Diane and Mark for their consent, trust and assistance; Chris Ford, my creative writing tutor, for his encouragement to begin this project; Rob Atherton, the older brother I never had, for invaluable feedback on early drafts; Doris Sumner and Inez Ashworth, the Golden Girls, for laughing their way through the final draft; Rita, for taking the time to read my manuscript and for her kind words; to the team at The History Press, for giving me the opportunity; and last but not least, Jean, the girl from the launderette who became my wife and best friend, for her unwavering love, support and patience.

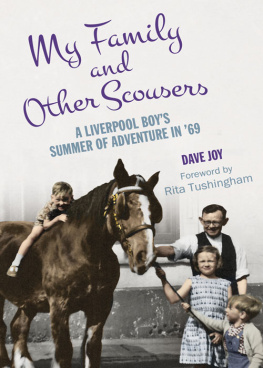

My Family and Other Scousers has such charm and innocence. It tells of a young boys summer of adventure, when children had the freedom to play outside and use their imagination, taking them on great daredevil adventures where nothing was impossible.

We see how important family is, and how much they support and love each other. Young Deejay spends precious time with his beloved father on his milk round and revels in his familys great affinity with their working horses.

We are taken on wonderful journeys through the district of Garston, described with such clarity and affection that, as a reader, you are transported there too. Being from Garston myself, it brought back many childhood memories for me.

My Family and Other Scousers is a pleasure to read, and you will feel privileged to have spent the summer of 1969 with the Joy family.

Rita Tushingham, 2014

Youre a dirty old man, Eck Joy, said me mum.

Im not old! laughed me dad.

Some things never change.

The end of the 1960s was an exciting time to be an eleven-year-old. Liverpool born and bred, I had lived through a decade of social change, technological advancement and human achievement. Gone were the days of austerity and hardship that my mother would complain about every time she lectured us kids that we had never had it so good. On the cusp of what we expected to be an even more exciting decade, my friends and I looked to the future with huge doses of youthful optimism.

We already had first-class stamps on our letters and decimal coins in our pockets; the pill was available on prescription; Francis Chichester had sailed single handed around the world; the first human heart had been transplanted; a few of us had colour television; and, of course, we all had the World Cup and Thunderbirds. If you lived in Liverpool you were particularly proud, because us Scousers had the Beatles and Cilla Black and Rita Tushingham. Now, jumbo jets were set to fill the skies, Concorde was ready to fly faster than the speed of sound and, most exciting of all, Apollo 11 was speeding its way to the Rocky Raccoon, one step away from winning the space race.

Despite all of this, and even though the swinging changes of the Sixties really were fab, it was nice to know that some things, good things, did not change. From my earliest memory, Mum had always scolded Dad for being old in some way or another: a dirty old man, a miserable old bugger or a silly old fool. Dad always laughed when he gave his ritual denial. His laugh was reassuring. It meant that everything was okay F.A.B. It meant that there was nothing going on in the world that we could not cope with, nothing bad enough to stop the laughter.

Dad had just walked out of the dock office after seeing someone on business. Lately, he had been seeing a lot of people on business. When adults used that phrase I knew it meant: none of your business. Nevertheless, I stood below the office window trying to earwig what was being said. I heard Dad laughing, but that was nothing out of the ordinary. Most of what I heard was just mumbling, though I had made out the word cheque being used repeatedly. I presumed that this was something to do with paying for the sawdust.

He called thank you to the half a dozen dock workers who had just helped carry the huge sacks of sawdust from the quayside saw mill and loaded them into the back of the milk van. They did not need to help; we could have managed by ourselves. They came out to look at the horse.

Now that my earwigging was done, I raced Dad back to the van, climbed in and sat myself on top of the sawdust sacks like the King of the Castle. I breathed in the warm scent of freshly cut timber. With two clicks of his tongue and a shake of the reins, Uncle George urged Danny to walk on.

Danny was the oldest of our three horses and he no longer did the milk rounds as often as Rupert and Peggy. It was a long haul up Dock Road and it was best for him to take his time. And time was something I felt we had in abundance: this was the first weekend of the six weeks that would make up the school summer holidays. Dad and I had risen at six oclock and then cycled down Chapel Road to the dairy him on the road and me on the pavement. We had done the bottom round with Rupert and the top round with Peggy. Then, Dad and Uncle George had decided to squeeze in a sawdust run before lunch and take the opportunity to give Danny a bit of exercise.

I had done the rounds and the sawdust run on many occasions before, either at weekends or during school holidays. They were regular events for me, for my older sister, Ann, and for my younger brother, Billy. But this summer was going to be different. This was going to be the summer for which I had waited years. In the past, Ann had slept over at the dairy and spent whole days working with Dad. When I had asked for the same privilege I was told Youre too young; you can when youre older. That became Mum and Dads stock answer, but I would not let the matter rest. Then, after what must have been two years of moithering, I applied a dose of logic to my argument. I pointed out that it was at the age of eleven that Ann was allowed to stay at the dairy. That was it, I had them I could not possibly be too young any more.

Even so, it had taken them yonks to come to a decision. I could not understand why. Mum and Dad seemed to spend a ridiculous amount of time discussing it and what was more, they would go into the front room to discuss it; we only used the front room at Christmas or when we had guests. If I walked in, they would immediately cease their conversation, so I knew they were talking about it. Why the big debate? This was not exactly a life-changing event and quite frankly I thought it was taking favouritism a bit too far. But finally, my request was acceded to and arrangements were put in place for the coming summer: I would accompany Dad to work whenever I liked (within reason) and in the middle of the holidays I would sleep over at the dairy. This was my first day working at the dairy. One day I would do this for a living, but for now this was one small step in that direction.

I took great delight in being there, working with the horses and spending time with the adults, especially with my dad. He was one of those people who had been vaccinated with a gramophone needle he loved to talk and I loved to listen. He seemed to know so much and seemed to take pride in letting you know how much he knew. Mum called him the Encyclopedia Eck-tannica full of useless information, she said. I did not think it was useless, though I thought it was fascinating, even though I had heard most of his stories many times before. I was already well practiced at getting him started. I just had to ask him a question. It was like switching on the radiogram, generating a constant stream of verbal information. On this particular morning, these question-and-answer exchanges between the two of us made up for Uncle Georges usual abstinence from conversation. Dad described Uncle George as being a backbencher, which meant he did not say much. He would say just enough to communicate his meaning no more and no less. For most of the time, this consisted of the word Aye. But somehow, Uncle George was able to make that one word mean different things, depending on the context: an affirmation, a question, a complaint, a criticism, a request, a lament even an expletive!