First Published 2008

This revised and expanded edition published 2014

Transit Lounge Publishing

95 Stephen Street

Yarraville, Australia 3013

www.transitlounge.com.au

info@transitlounge.com.au

Copyright Carl Cleves 2008/2014

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher.

Every effort has been made to obtain permission for excerpts reproduced in this publication. In cases where these efforts were unsuccessful, the copyright holders are asked to contact the publisher directly.

Design by Peter Lo

Printed in China by Everbest

E-ISBN 9781921924637

A cataloguing record for this item is available from the National Library of Australia

For Tashi

Contents

A shotgun wedding

A Double-edged Sword

When I was in my final year of law studies at the University of Leuven in Belgium I discovered a double-edged sword hanging over my head: obligatory service in Belgiums military force, preceded or followed by an apprenticeship as a young lawyer with an older conservative barrister, a friend of my father. I had returned several months late to university after an extended journey as a young, on-the-road beat-poet, folk singer. I had played to drunken Swedes in the bars of Sitges, busked in Barcelona, slept in caves in Ibiza and under the bridges of Paris. Arriving in the bohemian London of the mid-sixties I was taken under the wing of Judith Piepe, a matriarchal social worker and a kind-hearted angel with a mission: to salvage wandering folk musicians and nurture them in times of need. Through her I had met Paul Simon before his days of fame, Al Year of the Cat Stewart, folksinger Jackson C. Frank, and legendary guitar players Bert Jansch, John Renbourn and the Reverend Gary Davis. I sang at Les Cousins in the heart of Soho. I was initiated. Coming back to Belgium, I was in no mood to serve my sentence: the army or the courts. I had to find a way out.

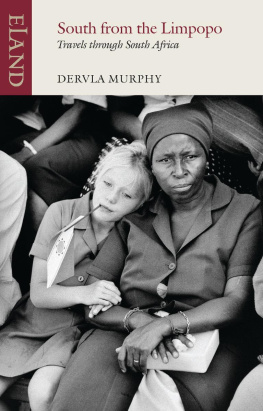

Scholarship applications are like buying lottery tickets: big dreams with few winners. A university in Thailand had been my first choice, my main criteria being the pictures of gorgeous girls in travel magazines. Since a good knowledge of the Thai language was required and the closing date for applications was only ten days away, it seemed a lost cause. Another option was South Africa. I knew little about the country except for the fact that it had a multicultural and multiracial society and that it was ruled by a harsh system called apartheid. Multicultural countries have always fascinated me. Traditions fertilise and cannibalise each other, and new hybrid forms of art, particularly music, are fostered. This had happened in the USA, in Brazil, in the south of the Sahara where Arab meets African, in India, along the Asian trade routes and West African ports, in the Caribbean, New Orleans, Tashkent and Salvador da Bahia. I decided to try my luck.

Within one week I somehow managed to obtain the necessary documents and references from my professors in time to meet the deadline. I had much catching up to do at university and over the next few months I forgot about it. There were one hundred and sixty applications and three places. It was a long shot. Even when the news came that I was amongst sixteen pre-selected students, I didnt rate my chances. But one autumn morning an official letter arrived in the mail informing me that I was selected to spend one year at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg to study international law. I couldnt believe my luck and Beatrice, my girlfriend at the time, and I got drunk on that same night.

Beatrice was seventeen, my first real passion. We had met as teenagers in the cafes and pubs of the Flemish town of Mechelen. I was a virgin young man, brought up in Catholic boys schools, entering university. My dad was a respectable judge. Beatrice came from a dysfunctional family and had left school. She was younger than me and had had lots of boyfriends. Wiry with an elegant femininity she gave the impression of a fallen angel. We, like most of our friends, drank a bit on the weekend. She could drink me under the table. Sparing of words, she was guarded with her thoughts. I was smitten with her mystery, attracted to her wildness. We had been having an on/off love affair for a year or so, hanging out together around the folk and jazz clubs, drinking and petting in the back of my dads car and in friends houses, both of us loners, heading for the wrong side of the tracks. My parents hardly communicated with me and disapproved of my musical wanderings and lifestyle. She couldnt handle the ambience at her home and spent afternoons and nights in bars.

When the scholarship offer came it seemed a perfect escape. Beatrice wanted to come along on this trip. Our indignant Catholic parents insisted on a marriage. To elope would result in scandal. Mechelen was a small town and the wedding of the oldest son had to do justice to the family honour. There would be many presents and, of course, a wedding feast. As part of the bride price her father Gustaf offered to pay her fare. It sounded like a good deal. My hair was cut short and my beard shorn. In the photographs we looked like two children in dress-up. We got married in a gothic church, the bride in white and me in tails and top hat, and left the country on that same night. The wedding presents remained unwrapped in the attics of our parents for years. I kissed the army and the drab circle of lawyers and black frocks goodbye. In the morning we sailed from Rotterdam. Destination: Africa.

South Africa

We left the cold and sombre North Sea and the gloom of the European winter behind without regrets. Steaming into Tenerife the sun broke over the Canary Islands. We were further south than wed ever been. From the bow of the ship we caught our first glimpse of the African continent, scanning the horizon through binoculars for the thin line of the Senegalese coast. Twenty-six days on an ocean liner. Around us nothing but the waters of the vast Atlantic, whales and dolphins. For someone used to hitchhiking and sleeping rough in the fields and underneath trucks, life was a cruise. Three-course meals, swimming pool and cinema; playing tennis, dancing at a nightclub and making love to the rocking of the ship. Who could complain? We both were sick as we sailed around Cape Horn. The ship visited Cape Town and stopped in Port Elizabeth and East London before we finally disembarked in Durban from where we took a train to Johannesburg.

My first visit to the Witwatersrand University was a disaster. Though it had the reputation of being the most progressive university in South Africa, my impression was one of extreme conservatism. Students sported crewcuts and blue blazers with yellow stripes. All were white. The sixties had not made it past South Africas strict censorship laws. Bob Dylan was banned and so were the Beatles after John Lennons off-the-cuff remark comparing their popularity to Jesus. There was no TV. It was considered dangerously subversive. I stood out like a sore thumb clambering my way up the steps of the Law Department to meet the Dean of the Faculty and introduce myself. I had grown Elvis-style sideburns on the trip over and was on crutches as I had broken three toes in an unfortunate misunderstanding with the ships officers during the baptism ceremony that traditionally takes place when one crosses the equator for the first time. I wore a Spanish boot on one foot, and the other was in plaster with the leg of my jeans cut off. The Dean studied my young wife and me from behind his tortoise-rimmed glasses.

Next page