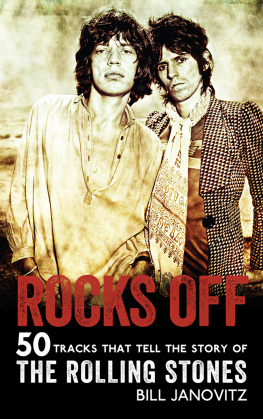

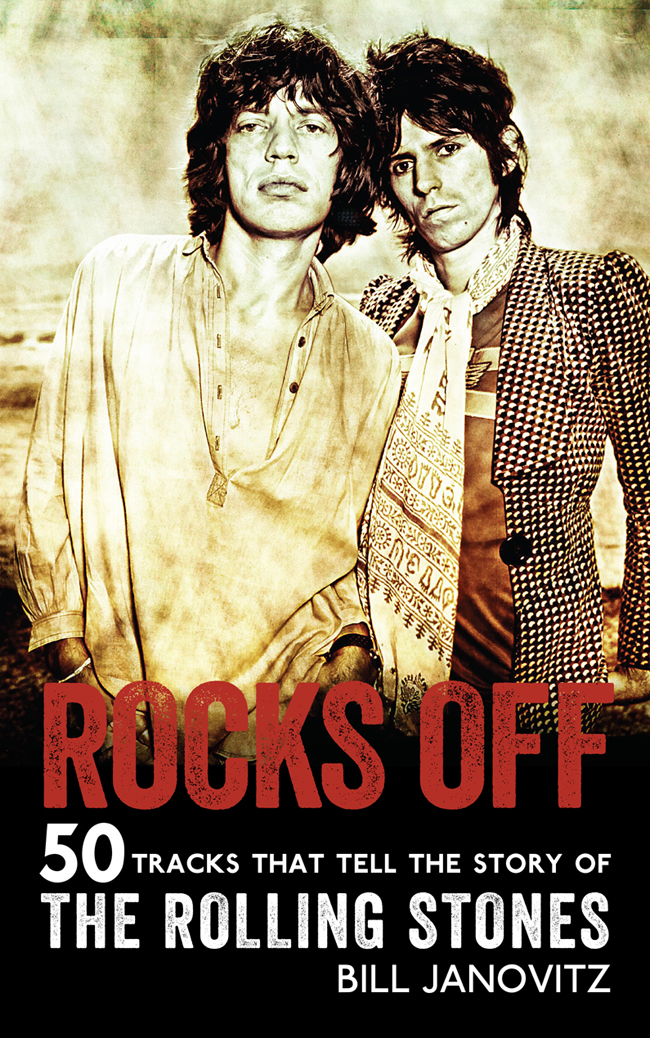

Bill Janovitz is a singer, guitarist and songwriter in the band Buffalo Tom. He has also released four solo albums. He wrote Exile on Main Street about the iconic Stones album and has written extensively for the All Music Guide online site. He lives in Massachusetts with his family.

First published in the United States of America in 2013 by St Martins Press. This edition

published in Great Britain in 2014 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

The moral right of Bill Janovitz to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted

by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in

any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise

without the express written permission of the publisher.

Introduction

Its the Singer, Not the Song

Ive worked out that Id be 50 in 1984. Id be dead! Horrible, isnt it. Halfway to a hundred. Ugh! I can see myself coming onstage in my black, windowed, invalid carriage with a stick. Then I turn around, wiggle my bottom at the audience and say something like, Now heres an old song you might remember called Satisfaction.

Mick Jagger, 1966

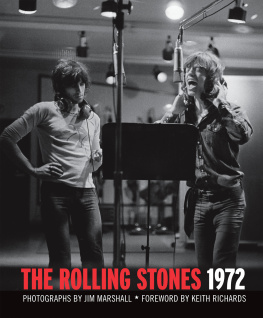

J ust as I was formulating the proposal for this bookI mean to the day I finally met a real live Rolling Stone. Not just any old Rolling Stone, but the man himself, rock n roll incarnate, Keith Richards. I happened to be fortunate enough to be attending the 2012 presentation of the first PEN New England Award for Song Lyrics of Literary Excellence, at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston. It was being presented to two of the greatest song lyricists of our time, Chuck Berry and Leonard Cohen. I was even luckier to be able to be in the green room prior to the ceremony. I was there with a friend who had been tapped to give the opening remarks and invited me to come along.

In the green room was an astounding assemblage of talent, artists who were taking part in the honoring of these songwriters: Chuck and Leonard, of course, along with Elvis Costello; Paul Simon; Shawn Colvin; Peter Wolf; and authors Salman Rushdie, Bill Flanagan, Peter Guralnick, and Tom Perotta.

Oh, and Keith Richards.

After the myriad of Mount Rushmorelike group shots so amazing that they should make the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame jealous, Keith slipped out to somehow procure the only adult beverage in the JFK Library. I was just there as a fan, trying to almost literally change into a fly on the wall, as to stay clear of possibly injuring one of the legends, all the while thinking such surreal thoughts as, I wish Paul Simon would move a little bit. He is blocking my way to Keith Richards. When Keith came back into the room, however, he sidled up next to me and placed his drink on the console table that was between us.

Now, I am not one to be impressed with celebrity or fame on its own. Ball players, actors, and local television meteorologists are all fun to meet, sure. But as an unreligious man, these musical artists are demigods to me: those who know, who have tapped into my consciousness. And none of them there had a more direct line into my soul than Keith. I have to say something, I thought. And so I did.

Hi, Keith. I just wanted to say hello, I said, shaking his hand as he smiled warmly. I mean, what do I say to Keith Richards?

His response immediately defused the tense and potentially awkward situation. Ah, hey, thank you, he growled. And in what came across as deeply sincere humility he quickly added, I feel the same way about Chuck Berry, man.

Yes, well, it is so great that he is being recognized for his lyrics in particular, I noted.

Exactly. I mean, some of the greatest songs, and some of the saddest, he explained. Like, Memphis Tennessee, one of the saddest of all time: hurry-home drops in her eye, I mean Here, he put his hand over his heart and opened his mouth, speechless with genuine awe.

I did not tell him I had written a book about Exile on Main Street, or that I was planning another book about what his body of work had meant to me. I had no agenda. I just wanted to speak with him as a fan, if not a fellow guitarist/songwriter.

And so that is how I present this book, as an unabashed fan who grew up with this music; whose career path was influenced by these records; and who, as a professional recording and touring musician, hopes to add some insight to the massive Stones canon.

The point of view of this book assumes readers are familiar with much of the bands history, and many of the songs, but I hope to dig into some underappreciated album gems. It hopefully also serves as a listening guide from the perspective of a professional recording musician (albeit one slightly more obscure than, say, the Rolling Stones), songwriter, and music writer. I hope to offer new insight and spur readers into dusting off and listening to the subject tracks. The songs are not all necessarily my favorites; they were chosen, in part, to tell the story of fifty years of the band. If the book had been selected only on the basis of my favorite tracks, it would have ended around Tattoo You (1981).

Asked once why his impressive library contained no books on music, Keith Richards replied that music is for listening, not reading about. Okay, lets listen together.

Prologue

19611963: The Run-up to Recording

I ts an almost apocryphal tale, and there might be as much mythology as sepia-toned documentation to how five pasty middle-class English kids found each other and discovered their lot in life in some obscure, scratchy American blues records. How two of these young men, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, boyhood friends who had lost touch during adolescence, bumped into each other on a Dartford train platform at the age of nineteen. It would have been just a quick, ello, howve you been? had Mick not been carrying an armful of hard-to-find records he had just ordered through the mail from Chess Records in Chicago. The artists Mick collected were magical names to the pair, who were venturing halfheartedly into universityMick at the London School of Economics (LSE), and Keith at Sidcup Art College. So instead, we have an origin story.

The fact that the two had independently stumbled across this uncommercial form of musicunknown to but a small portion of fanssignified to each that the other was hip. Their boyhood friendship was rekindled on the spot. Mick had been singing and learning to play blues harp (harmonica), and had played a gig or two sitting in with bands at so-called jazz clubs around London with a friend and other like-minded soul, Dick Taylor, another guitar player who attended Sidcup. Keith had embraced guitar as a boy after his mother bought one for him, teaching himself Chuck Berry numbers from records. The three of them started to jam, with Taylor switching to bass, and named themselves Little Boy Blue and the Blue Boys.