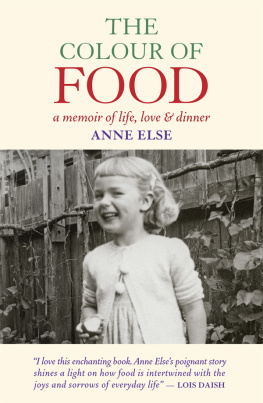

Contents

In loving memory of

Harvey McQueen,

who shared kitchens, tables and beds

with me for thirty years.

A note on recipes

Recipes for many of the dishes described in this book can be found at the end of this ebook, and on my blog Something Else to Eat .

First edition published in 2013 by Awa Press, Level Three, 11 Vivian Street, Wellington 6011, New Zealand.

epub ISBN 978-1-877551-92-5

mobi ISBN 978-1-877551-93-2

Copyright Anne Else 2013

The right of Anne Else to be identified as the author of this work in terms of Section 96 of the Copyright Act 1994 is hereby asserted.

Copyright in this book is held by the author. You have been granted the right to read this ebook on screen but no part may be copied, transmitted, reproduced, downloaded or stored or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system in any form and by any means now known or subsequently invented without the written consent of Awa Press Limited, acting as the authors authorised agent.

National Library of New Zealand Cataloguing-in-Publication DataElse, Anne.The colour of food : a memoir of life, love and dinner / Anne Else.ISBN 978-1-87755-192-5 (epub)ISBN 978-1-87755-193-2 (mobi)1. CookingSocial aspects. I. Else, Anne. II. Title.

Cover design by Pieta Brenton

Find more great books at awapress.com

To start with

Im three, and Im sitting in the sun on the grass beside the narrow strip of garden in our long skinny backyard. Before Mum sees me I reach out for a handful of rich dark soil and fill my mouth with its crunchy, crumbly, satisfying warmth.

Now Im four, watching Mum as she cuts a neat square plug out of an apple. She hides sugar in the hole for me to find and puts back the plug, the cut-lines invisible in the green skin.

When I think about my childhood its the food I remember most. Apart from that delicious dirt, what I ate was just the standard fare of thousands of 1950s New Zealand homes, yet I knew how much it mattered. Even more than the Everglaze summer dresses and knitted winter jumpers with matching skirts, food meant pleasure, love and safety. But it could also tip over into revulsion, rejection and danger.

The memories of food go far beyond childhood. Since the day I left home to get married at the age of nineteen, what I have eaten and cooked, and what has been cooked for me, have often seemed to hold the essence of who I thought I was or wanted to be, and how I lived with the people I loved. Food has also been a creative challenge and a daily source of sensual delight.

I havent tried to cover every aspect of my food experiences over the last sixty years. Instead I have lifted out what seem to me the most interesting and intensely flavoured morsels in the whole complex, many-layered casserole as it has slow-cooked its way through my life. Theres a strong emphasis on eating and cooking at home, where food and feelings are always so deeply blended but home has moved from Auckland to Albania to London to Wellington, with side trips into French territory, real and imagined.

The book doesnt conform strictly to the passing of time. It moves backwards and forwards through the years, so the people Ive shared my life with appear at various intervals. For example, Harvey McQueen, my second husband, turns up well before I write about meeting him in 1979.

Its never easy to turn and look intently into your past, then try to bring back what you find there. I hope these ten portions of my life, closely connected but each with its own distinctive character, will be as satisfying for you to read as cooking them up has been for me.

Anne Else

Chapter 1

More than enough

Its school holidays and Ive spent the morning with Mum while she gets on with the breakfast dishes and the downstairs cleaning, listening to Aunt Daisy, Doctor Paul and Portia Faces Life on the radio, while my little sister plays in the backyard. Just before lunchtime Mum gives me three shillings and I run up the lane and around the corner to Davenports Bakery for three ninepenny meat pies, hot from the oven. We eat them with soft white bread and butter, and tomato sauce from the red plastic tomato. With only the three of us, theres no need to hurry: Dad wont be home needing his dinner until half past five, and for the time being Mum seems to be on holiday too.

It took me years to recognise that it was my mother who sowed the seeds of the pleasure I get from food. She got profound satisfaction from producing a constant generous supply of meals for herself, her husband and her children. When she was a child, that reliable security had been mostly missing. Many of the stories she told me turned on how hard it had been for her mother, Harriet, to produce any kind of food at all. The stories were like a real-life version of my copy of Grimms Fairy Tales , an old small-print edition of a scary nineteenth-century translation never intended for children. Despite all the bread, cheese, cabbage and sausage in its pages, they were also full of hunger and want, often linked with making a foolish marriage to a stranger.

Harriet did this twice. Her own family was irreproachably respectable. Her father, Arthur, was a well-to-do hardware merchant who had sailed to Gisborne from Ireland in 1867 with his much younger bride, Frances Selina. Frances produced ten children and all of them lived. As my mother told it, Harriet was the youngest and most beautiful of four sisters, but she was painfully shy and sensitive, and when her family started taunting her for being an old maid she vowed shed let any man have her. At twenty-nine she met Hugo Korth, an exotic Polish exile, who fathered her three children Rurik, my mother Ryda, and their brother Raymond.

Korth turned out to be a shiftless drunkard. He used to steal vegetables from gardens to feed his family, running home with them at night through the dark streets.

In all the stories about not having enough to eat, someone is running. Harriet leaves her baby in the tent her husband has put up for them to live in, climbs barbed wire fences, and runs across paddocks to get milk from a farmer. She gets her three children to run around the dining table where she sits with one boiled egg, feeding each a small spoonful as they go past, turning it into a game. She borrows threepence from a neighbour and sends Ryda running to the butcher to buy bones for soup.

Harriet had to borrow the threepence because the funeral of her second husband had left her penniless. Korth had brought this man home after meeting him in prison; you would have thought that was warning enough. Mr Steele he was always Mr Steele in my mothers stories was handsome and well-educated, and he wooed Harriet by bringing her food for her children. In 1913 she managed to get a divorce from Korth on the grounds of habitual drunkenness and failure to support, and the next year she married Mr Steele. According to Mum he was a confirmed bachelor who should never have married a mother with children. He became jealous of Harriets love for them and showed it through food: he would buy good fruit for her and spotted fruit for them.

It didnt take Harriet long to discover that Mr Steele was a con man and a drug addict. As the money disappeared and his gentlemanly act fell apart, she came up with an idea. Sheets were always wearing out down the centre and having to be turned, sides to middle. Why not reinforce the centre with double weaving so the sheets would last longer? She paid a few shillings to protect her patent and the Scottish firm of Findlays agreed to pay her a royalty of one and a half percent on all Backbone sheeting sold. With the money, she managed to keep her family fed, paying the grocer every three months when she got her cheque.