Whats it made of? I heard an art dealer ask a businessman standing beside him, as they gazed at the extraordinary new sculpture by Anish Kapoor at Gibbs Farm.

The businessman laughed. Money, he said.

It is obvious to anyone that this artwork could not have been created without considerable financial resources. In truth, however, Dismemberment, Site 1 is made of a blood-red PVC skin, ribbed with Kevlar cables and stretched taut between two oval rings of steel, each weighing 45 tons. These rings sit on two concrete foundations that reach 25 metres into the earth.

Its form stirs the imagination: perhaps its a trumpet. The artist talks of the flayed skin of heroes in Greek mythology. Its unofficial title amongst guests that day, Pussy Galore, points to a more ribald interpretation. But it is not just its form that provokes powerful reactions; it is the combination of its size (25 metres high, 85 metres long), its position cutting through the top of a hillside and its colour, standing in sharp contrast to the green grass of a north Auckland farm.

As I walked around the February 2009 gathering to celebrate the completion of the Kapoor sculpture, everyone was talking, trying to decide whether Alan Gibbs was mad or a courageous genius, or a touch of both, for commissioning such works and pouring such resources into his sculpture park, Gibbs Farm. Theories abounded. Was Gibbs creating a great artistic monument? Was he thumbing his nose at society, delighting in his freedom to provoke reactions? Was he just having serious fun? One thing most of the guests agreed upon that hot summers day was that the world was a richer place because of him and of what hed done.

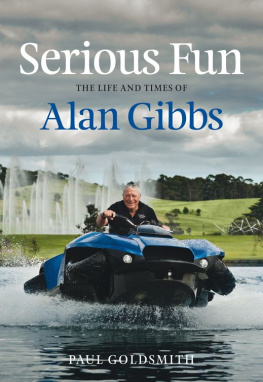

The idea that Gibbs could create one of the worlds great sculpture parks on a farm overlooking the Kaipara Harbour, a neglected and unvisited backwater north of Auckland, is outrageous. But no more outrageous than many of Alan Gibbs big ideas over the years: that in his mid-twenties he could build the first genuine New Zealand car, the Anziel Nova; that normal business disciplines and practices could be applied to the nations public health system; that the best way to make money in business is to persuade other people to give it to you; that he could double the utility of a car, extend human freedom and transform transport patterns around the world by creating the worlds first high-speed amphibious vehicles.

The scale of his ambition has been vast. Hes hurled his copious energy, enthusiasm, determination and resources and a powerful intellect into all his projects, and in his 72 years hes met with plenty of frustration and several reversals, as well as achieving many notable successes.

At the time of writing, Gibbs is going to market with the worlds first high-speed amphibious vehicles. Hes starting with three versions: the Phibian, a large amphi-truck designed, amongst other uses, for all-terrain search and rescue activities; the Gibbs Humdinga, a four-wheel-drive beast that can also skim across rivers and harbours; and the Gibbs Quadski, a cross between a high-speed quad bike and a jet ski, targeted at the recreational market, particularly in the United States. These are the first offerings from a series of amphibians that he plans to roll out over the next few years.

Until Gibbs launched the Aquada in 2003, there had never been a roadlegal amphibian capable of going fast on land and water. The best of the pre-Gibbs amphibians had managed just twice walking speed on water. His game-changing project stemmed from his simple desire to access the Kaipara Harbour across the tidal mudflats from his property.

It has extended into a 17-year quest that so far owes him US$200 million and has thrown up a seemingly inexhaustible supply of complex problems to solve. In the process his business, Gibbs Amphibians, has made stunning technological advances, registered dozens of patents and produced something in the Aquada that captured the publics imagination internationally when it appeared in 2003.

But much more effort has been required to achieve Gibbs ambition for the project, to create a revolutionary new technology. Fortunately for him, the stimulation that this and other challenges provide is his oxygen. The quest is nearly as rewarding as the resolution.

Gibbs has had a long and highly productive business career. By adopting a low-risk style of deal making, keeping his affairs simple and choosing good partners, he amassed one of New Zealands largest personal fortunes during the 1980s and 1990s. His early career was an exemplar of capitalisms creative destruction as he carried out the necessary restructuring of many inefficient companies and organisations so that either they could survive and add value in a world of open competition, or the resources invested in them could be put to better use elsewhere.

Since then hes used the wealth he has generated as a springboard for the entrepreneurial challenge of successfully taking to market the worlds first high-speed amphibians.

But business has only ever been part of his life; something on which to focus intensely at times, yet not all-consuming. Hes spent as many of his days reading history and travelling to the ends of the earth and everywhere in between, learning from experience, and thinking about the purpose of life and the nature of man. By his early forties, Gibbs had arrived at a set of strong views about the natural order of things, the central importance of free markets and the dangers of big governments, overly confident planners and arrogant intellectuals.

His thinking, naturally, was shaped first by his parents, but subsequently it has been greatly influenced by Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, especially Hayeks last book, The Fatal Conceit: The errors of socialism. One of Hayeks essential insights was to see the wisdom borne out of the millions of voluntary decisions made every day by people operating in free markets and the folly of socialists who supposed they could plan for better outcomes and use the modern states powers of coercion to bring those plans to fruition. In their conceit, the socialists and planners show no awareness that there are huge limits to our knowledge and reason.

Born of missionary stock, Gibbs has wanted to convince people, New Zealanders mainly, that their society would function much better with less government. Between 1984 and 1988, when Roger Douglas was Minister of Finance in the Fourth Labour Government, Gibbs influence on public policy was significant, contributing to a process of economic restructuring and reform that restored the country to a more sustainable economic path. As chairman of the board tasked with commercialising one of New Zealands first state-owned enterprises, he led opinion and provided a powerful example of how changes that previously seemed impossible could be achieved. He pushed further in the early 1990s, supporting think tanks, setting up a radio station and helping to establish a new political party.

These efforts earned him the title unofficial high priest of the New Right,

This book has had a long gestation. I first met Gibbs in February 1997, when I began researching and writing a history of his family in New Zealand and a biography of his father, TN Gibbs. When those tasks were completed, he asked me to write a book on Te Hemara Tauhia, a Maori chief from the nineteenth century who is buried in a small fenced grave on Gibbs Farm. Having been flung around the insides of various vehicles as Gibbs has attempted to climb crazy hillsides, and having watched the evolution of his sculpture collection and the amphibian project, while in the meantime writing about several of his contemporaries, I have long wanted to attempt the Gibbs story. Not just what hes done, but to try to convey what he is like to deal with.