For Vic, with my love

CONTENTS

I am hugely indebted, in all manner of ways, to:

Chris Yates, Simon Benham, Mathew Clayton, Abbie Wood, Jeff Barrett, Ian Spicer, Edward Barder, Simon Legg, Trevor King, Ron Greer, Mark Hassell, Teddy Morgan, Patrick Molloy, Ian Garrett, Les Darlington, Kate Davidson, Anna Jones, the Alness boys and the old man of Loch Shin. Thank you to Stephanie Turner for her picture, Trout.

Above all, special thanks are owed to the clan Mum, Dad, Vic, Chris, Edward and Ricky, who is as much my hero now as he was when we were boys.

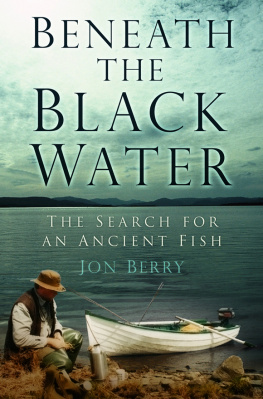

When we were boys, my brother Chris and I fished the loch below Kildermorie Lodge every summer. If we suspended worms beneath plastic bubble floats and cast as far as we were able, small trout would seize the bait and come cartwheeling to the shore as we wound in our lines. Cousin Ricky our older, wiser guide on these holiday adventures was always on hand to untangle knots or keep the midgies away with clouds of cigarette smoke. When spared these duties, he caught the most trout and usually the biggest too. The three of us fished and camped and built fires, revelling in the knowledge that our parents were 10 miles away down a slow road. It was the kind of freedom that only young boys could fully understand.

The fish we caught were magnificent and, at 10 inches or less, were perfect for the blackened frying pan that came with us. On the back of our permits, somewhere in the small print, it said that no trout of less than 12 inches was to be taken, but local size limits dont apply when you are still some distance from your teens and we were green enough to believe that trout grew no bigger.

One afternoon, as we sheltered in the boathouse from the rain, Ricky told us about the old fishing lodge further down the valley, beyond the point where the loch became the River Averon, which had a stuffed fish in the entrance hall. This giant brown trout, heavily spotted with a hooked kypey jaw and black head, weighed close to 15lb and was nearer 3ft in length than 2. It was almost too spectacular to believe. Trout were small, something we held in one hand, but Ricky had been to the lodge once and had seen the monster for himself. He told us it was a ferox trout, a rare survivor from the Ice Age primitive, predatory and almost uncatchable. When the weather relented we left the sanctuary of the boathouse and fished on, catching more small trout, but I was distracted. A bigger fish had swum into my head.

It left as suddenly as it had arrived. We were young and lived in Hampshire; giant Scottish trout and ancient ones at that had no legitimate place in the imagination. They may as well have been dinosaurs. Eels and perch and tench were real and could be caught from the farm ponds near home, and my brother and I pursued them with vigour. Family holidays still took us to Scotland and to Cousin Ricky, but rarely back to the old boathouse at Kildermorie. The story of the stuffed fish in the lodge was never repeated.

Inevitably, the time came when Chris and I began to stay at home and our parents drove north to Alness without us; we were teenagers now and there were other adventures to be enjoyed. Some of these involved chasing large carp in an old monastery pond. Others took place away from the water in another reality populated by girls, guitars and cars. At 16 and 17 the visceral present was everything and we found little that resonated in unlikely monster stories. Life found its momentum in the next fish, the next chord and the next Youth Club fumble. Northern Soul, crafty fags and the onerous demands of O Levels were real and could not easily be ignored. The old ferox trout and its Victorian captor were forgotten and a decade would pass before I would think of them again.

In 1997 I had to return to Scotland. My friend Martin, a London cameraman who spent much of his working life making pop videos, was with me. My own circumstances then were less glamorous; I was Head of History at an unremarkable comprehensive school, a fanatical carp angler and an unreliable boyfriend to Roo.

The road trip with Martin, above all else, was an attempt to put some space between me and an increasingly fractured relationship. Roo and I had been together for over four years and until that summer it had been special and tender, the best either of us had known. We had fished together, drunk together, grown into our twenties together. We shared a love of the same music and films, of the countryside and its wildlife, but busy lives had led us to take each other for granted and our relationship evolved into a friendship, and a sometimes distant one at that.

I was working too hard and escaping to the pond at every spare moment and our lives had marched on separately. Roo had friends whose names I barely knew; I had debts of which she was blissfully unaware. We shared a bed and an old VW Beetle, but little else of substance. Tellingly, when I had suggested that Martin and I might head north for a while, she had helped me pack and hadnt asked how long I would be gone.

Martin collected me late on a May evening, in a newly acquired but much-abused Honda saloon. It was cream with coarse tweed upholstery, high mileage and a capricious cruise control system that seemed to function entirely of its own accord. However, the stereo worked well and the road north was empty and we took turns at driving and sleeping. My partner had brought a few worries of his own and neither of us glanced in the rear-view mirror until we were well past the Scottish border. By sunrise we were pulling over for breakfast in Aviemore. Roo and work were hundreds of miles away and so were our problems.

It felt good to be with Ricky again. Much had happened since we had last fished together; diabetes had claimed his sight and necessitated a kidney transplant. He had married and become a father and acquired a reputation as the best ghillie on the river. The skinny teenager in the boathouse had become a thick-set man with full beard and sanguine complexion, but was still unmistakably my favourite cousin. His fly-casting was as effortless as I remembered and it was only when the light fell each evening that Martin or I would need to take his arm and guide him from pool to pool. He didnt ask why I had left it so long to come back he just led me to the fish, as he always had.

Rickys home town of Alness half an hour north of Inverness on the Cromarty Firth between Dingwall and Invergordon looked like I remembered. No neon signs or architectural behemoths had sprung up in my absence. The River Averon still ran through the heart of the town and the two-room Butt and Ben cottage where my mother had been born was still at the bottom of Coul Hill; fishing tackle and permits came from Pattersons Hardware as they always had, the academy kids still got their ice-cream from Italian Tony and the highlands of Easter Ross and the Black Isle owned the horizon. Martin loved the place immediately.

Not everything in Alness was the same and to most of its people I was now a stranger. As boys, my brother and I had often been accosted by ageing spinsters as we walked down the high street. They would pinch our cheeks and squawk about us being Val Frasers boys whilst stuffing coins in our pockets for sweets and chip suppers. Some would shuffle off recalling the handsome man in uniform who had whisked our mother away.

Next page