Guardian, 8 January 2010.

My Boy Butch

The heart-warming true story of a little dog who made life worth living again

Jenni Murray

For David, thanks for finally saying, Yes. J.

Contents

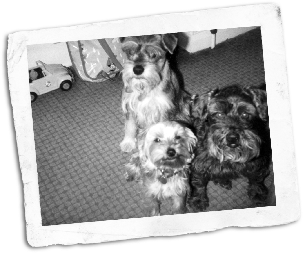

As I sit here writing, he is curled up amidst a pile of cushions behind me on the bed. He appears to be asleep but he isnt. He is alive to my every sound and movement. If I make as if to get up, one eye will open, peer out from inside his cocoon and hell leap into instant wakefulness and energy. He will follow me everywhere. He is, the family jokes, my shadow.

This book is about the dog who changed my life. Its about a Chihuahua, the smallest of dogs with the biggest of hearts, who came into my life at its lowest ebb.

A diagnosis of breast cancer had been confirmed on 20 December 2006. It was the day my mother died after a long battle with the cruelly debilitating effects of Parkinsons Disease. Quite how we struggled through Christmas I shall never know. My father suffered the immeasurable grief of a man who had adored the same woman for almost 60 years and had no desire to go on without her. He needed every ounce of energy I could muster. I had to face a mastectomy between Christmas and New Year, organise my mothers funeral and then begin a course of chemotherapy which would last for half the year.

In the midst of the exhausting effects of the treatment as I tried to keep the rest of the family, my two sons, Edward and Charlie, and my partner, David, in some semblance of normality and sanity my father succumbed to lung cancer in June. Thus, within a few short months, I, an only child, lost the parents who had always been a reliable rock throughout my life, faced the possibility of my own demise, had to accept that my children were now grown up and becoming increasingly independent, and that my partner was in as great a state of shock as I was.

He and I would rattle around the family home, which now seemed over-large and silent. I grieved for my parents and my health. He too was full of sadness. We had been together for almost thirty years, so my parents were family to him as they were to me and my children. But the greatest pressure, in the aftermath of all this sorrow, was a doom-laden sense that we were now the older generation; that we would be next to face the draining deterioration that ageing brings, and we were uncertain that doctors who predicted a good prognosis for me were telling us the truth.

It seemed that any plans for a fulfilling and energetic middle to old age might be scuppered by my illness; and David, who had never known me to be anything but a cheery livewire, constantly occupied by home, children, work and friends, suffered an unspoken terror that he, like my father, might be consigned early in the middle years of his life to caring for a sick woman or, even worse, might lose her altogether. The days passed heavily.

And then came Butch. His name is not altogether incongruous. He may be a mere Chihuahua, but he has the heart and stomach of the fiercest Rottweiler, and when we stay in the Wuthering Depths of my London basement flat on the days Im in the capital for work I no longer fear the night-time intruder, knowing he will warn me of any impending danger.

Butch began to replace tales of my children in the weekly newsletter that I write online for the BBC. He has become the star of the show, receiving presents he always wears his gift of a black leather collar with the diamante inscription bad boy, confirming that hes joined his mistress as a gay icon and regular enquiries as to his health and his latest antics.

At the literary festivals I have attended over the past months to publicise my last book, Memoirs of a Not So Dutiful Daughter, the first question is frequently, Hows Butch? Why didnt you bring him with you?

I am, I fear, upstaged, even in his absence!

His youth, verve and uncritical, unconditional devotion have made me look forward to getting up in the morning food, a walk, a game in the garden and to coming home no longer to an empty house, but to a smiling and enthusiastic welcome.

He is an affectionate, devoted and sometimes hilarious companion. He has made life worth living.

Chapter One

A Dog Is for Life

There was always a dog. If not real, then imagined. I dont precisely recall at what stage it began to dawn on me that the most powerless creatures on the planet seemed to be little girls, but I cant have been much more than a toddler when I developed a deep resentment of being bossed about. It had quickly become apparent that I was considered fair game for parents, grandparents, disapproving aunts and the gang of local big boys who tittered at any valiant attempt to join in with climbing a tree, kicking a ball or steering a tricycle. They made it quite plain they would as soon drown in the dirty duckpond as be seen actually playing with a creature that jabbered incessantly and sported (generally unwillingly) a ribbon in its hair.

But a dog, I knew partly by instinct, partly from the books my mother read to me would never snigger or criticise or make demands. It would revel in your company and obey the most peremptory of barked orders. Sit, heel, stay, roll over would be music to its ears. It would fetch the ball you were doomed to play with alone. Should you find yourself being beaten up by the biggest bully on the street a not uncommon occurrence it would tear out his throat in your defence. Should burglars dare to enter at the dead of night, it would rip out the seat of their pants and hold them, terrified, until the constabulary turned up.

In my vivid, infantile imagination I dubbed myself the mistress and ceased to be some pathetic, undersized weakling, expected to sit nicely, knees demurely together with neatly brushed hair and scrubbed apple cheeks.

At night, after the bedtime story, I dreamt that a heroic Shadow the Sheepdog lay snoring at the end of my bed as I slept or Lassie traversed the known universe to be at my side or Timmy and I strode about solving crimes and saving damsels in distress.

I begged and pleaded with my mother for a dog of my own. She was adamant that she had quite enough to do, thank you very much, with a house, a child and a husband to run around after. Why would she need the responsibility of a dog?

I know full well, shed say, that youll tell me youll look after it. But you wont. Ill be left to walk it, feed it, and Ill be hoovering all day to get rid of its hairs.

My mother was obsessively houseproud and, although I doubt she realised it at the time, had indeed articulated one of the first lessons in the canon of feminist commandments:

Thou shalt not buy any animal you are not prepared to clean up after. Men and small children have a tendency to lie about their readiness to attend to such matters.

Thus the lonely existence of an only child continued until the happy coincidence of two not entirely unconnected events. The first involved my disappearance. I was four. This was the 1950s and, apart from reading, listening to the wireless and being helpful around the house, there was not much to keep a child entertained at home.

Parents were relatively unconcerned about their youngsters playing out. In fact, for a mother whose work was staying home, cooking, cleaning, washing and ironing, it was something of a relief to have her offspring out from under her feet for an hour or two. There was none of todays dire warnings of stranger danger, nor were there enough cars on the road for incessant traffic to be seen as much of a threat. There must have been a degree of parental concern as I was frequently warned not to go off . Stay in the garden or the fields or the street where I can keep an eye on you.