BREATH

A Lifetime in the Rhythm of an Iron Lung

A Memoir

Martha Mason

Foreword by Anne Rivers Siddons

Introduction by Charles Cornwell

New York Berlin London

Copyright 2003 by the Estate of Martha Mason

Foreword copyright 2010 by Anne Rivers Siddons

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA HAS BEEN APPLIED FOR.

ISBN 978-1-60819-119-2 (paperback)

Originally published in hardcover, in slightly different form,

By Down Home Press in 2003

First published by Bloomsbury USA in 2010

This e-book edition published in 2010

E-book ISBN: 978-1-60819-320-2

www.bloomsburyusa.com

In Memory of

Willard Elmer Mason (1911-1977)

Euphra Ramsey Mason (1914-1998)

Gaston Oren Mason (1935-1948)

We do not see things as they are; we see things as we are.

T HE T ALMUD

CONTENTS

Living on the Edge When You Dont Know Tea from Turnips

My Fair Helper

A Thin White Curtain

My Best Friend

The Miracle of the Unwrapping

Rescued by Wonderful Wanda, Prozac, and a Dragon

Christmas Eve, 1945

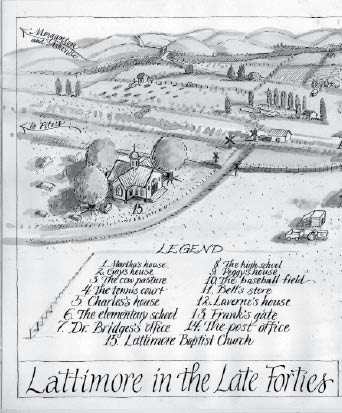

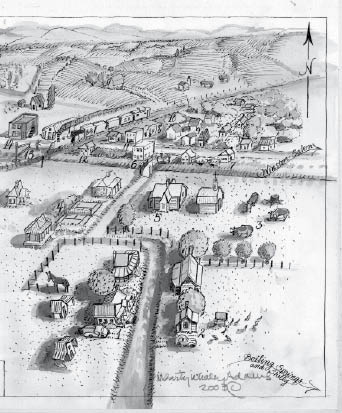

Lattimore in the Late Forties

A Farm of My Own

Boys

Pulling Another Brer Rabbit

A Spiders Web

The Long Yellow Barrel

Mrs. Lees Pythias

My Hometown Collectibles

From the Order of the Border to the Society of Phi Beta Kappa

You Can Go Home Again

Mothers Merry Twilight

April 15, 1998

The Old Girls Try Ostrich Burgers

S EVEN CYLINDRICAL FEET and eight hundred pounds of tempered steel, bright yellow. Air controlling pumps increase and decrease atmospheric pressure. Sometimes called a negative pressure ventilator. Medically considered noninvasive.

Iron lung.

To those of us who can remember when the sucking specter of polio prowled our summers, it is a fearsome word. It resonates in that most intimate of all places, the deepest one, where human flesh, human need, and blind technology collide. It is a cold lover, an inanimate womb, an indifferent savior.

To those who cant remember, it is likely to be an unknown word.

To Martha Mason of Lattimore, North Carolina, population 400-odd, it was, for sixty-one of her seventy-one years, the skin of her being.

But the essence of her heart, soul, spirit, wit lived in a vast, radiant world of friendships and books and music and vital, often clashing opinions and gusty joy, as well as the inescapable pain, sorrow, and rage that is given freely to all of us. She was never above the worlds woes. Spending the best part of her life in an iron lung just didnt happen to be one of them.

This book is her story, told in the rich words of a born writer. That she told it is a gift to everyone who will read it. That she told it is also as near to a miracle as most are likely to encounter.

After eleven years of a small-town Southern childhood sunny and free and lyrical as childhoods in those earlier times sometimes could be, she contracted the dreaded infantile paralysis that stalked those summers and was hospitalizedon the same day of her brother Gastons funeral. He died of the same virus that sickened her.

They put her into an iron lung and told her grief-stricken parents that she would not survive.

Incredibly, they told Martha that, too.

And from somewhere deep within, she pulled the words that would be her wings all her life: Yes, I will.

After a year in the hospital her parents brought her home to the old white house in Lattimore that would be home for the rest of her life.

She was quadriplegic. She could scarcely move her head on her pillow. Caretakers around the clock were necessary. She remembered thinking, on one of those first days at home, Where do I go from here?

The answer was words. She had always been a passionate reader; now her mother or caretaker turned pages for hours at a time. Later, she had an electronic page turner.

And she wrote. She dictated to her mother. Together, they made a writer out of a child who often forgot she was crippled.

She graduated first in her high school class. She and her mother attended Gardner-Webb College, and she was first in her class there, too. And later, at Wake Forest University, she was first, and also a member of Phi Beta Kappa. She and her mother did it together, in rented apartments, listening to classes on intercoms. Listening, listening.

The iron lung went with her everywhere.

Her selfless mother, Euphra Mason, was her linchpin and her true north. Marthas life became hers. They shared a world that might have been a strictured and sterile one, but was instead so full of friends and visitors and ideas and laughter and endless, endless talk that the old house fairly bubbled with it like a cauldron. Martha hosted a book club, a supper club, wrote newspaper and magazine articles.

There seemed no stopping the two Mason women, but then her beloved father suffered a stroke, and her mother, submerged in his care, no longer had time for dictation. Martha wrote for decades only in her head.

After her father died, Euphra Mason became someone her daughter had never known. Mini-strokes tipped her into a dementia. Once her greatest support, her mother now gave Martha rage, abuse, and physical pain. Inside her yellow submarine, Martha Mason became afraid for the first time in her life. Of her mother.

She also became, abruptly, the head of her household. She managed its affairs, handled all the transactions with the caretakers who were her constant companions, balanced budgets, ordered supplies and groceries. She also found, with the help of her beloved doctor, a medication that helped turn her angry mother into a biddable, sweet-tempered child. Now she cared not only for her home and herself, but for her mother, too.

It was a great effort, a dark time. Shouldering such loads without the catharsis of writing plunged her into a long night. And then friends led her to acquire a voice-activated computer with Internet access and e-mail capability. For Martha, it was rebirth. And when the words came pouring out again, they were about and for her mother. Martha began a love song to the most extraordinary woman she would ever know.

And along the way, other threads began to creep in the luminous childhood she wanted to recapture, the rhythm of her own life in the everlasting arms of the iron lung.

As a novelist, I know that there is no such thing as an ordinary life. All lives shimmer and pulse with particularity, with richness and texture. The life laid down in the pages of Breath is heart-stirring, transcendent, brimming with love and humor and intelligence and often what Martha called her sheer orneriness; with courage and an utter lack of self-pity and an earthy appetite for the joy that she wrested from her life. Her devotion to her friends and theirs to her sings on every page. Her loving, impatient, and wildly funny taming of some of her caretakers into heart-friends is the stuff of human comedy at its best. The breath of a fine writer stirs each page.

Next page