Published by Punk Planet Books/Akashic Books

2005 Bee Lavender

Punk Planet Books is a project of Independents Day Media.

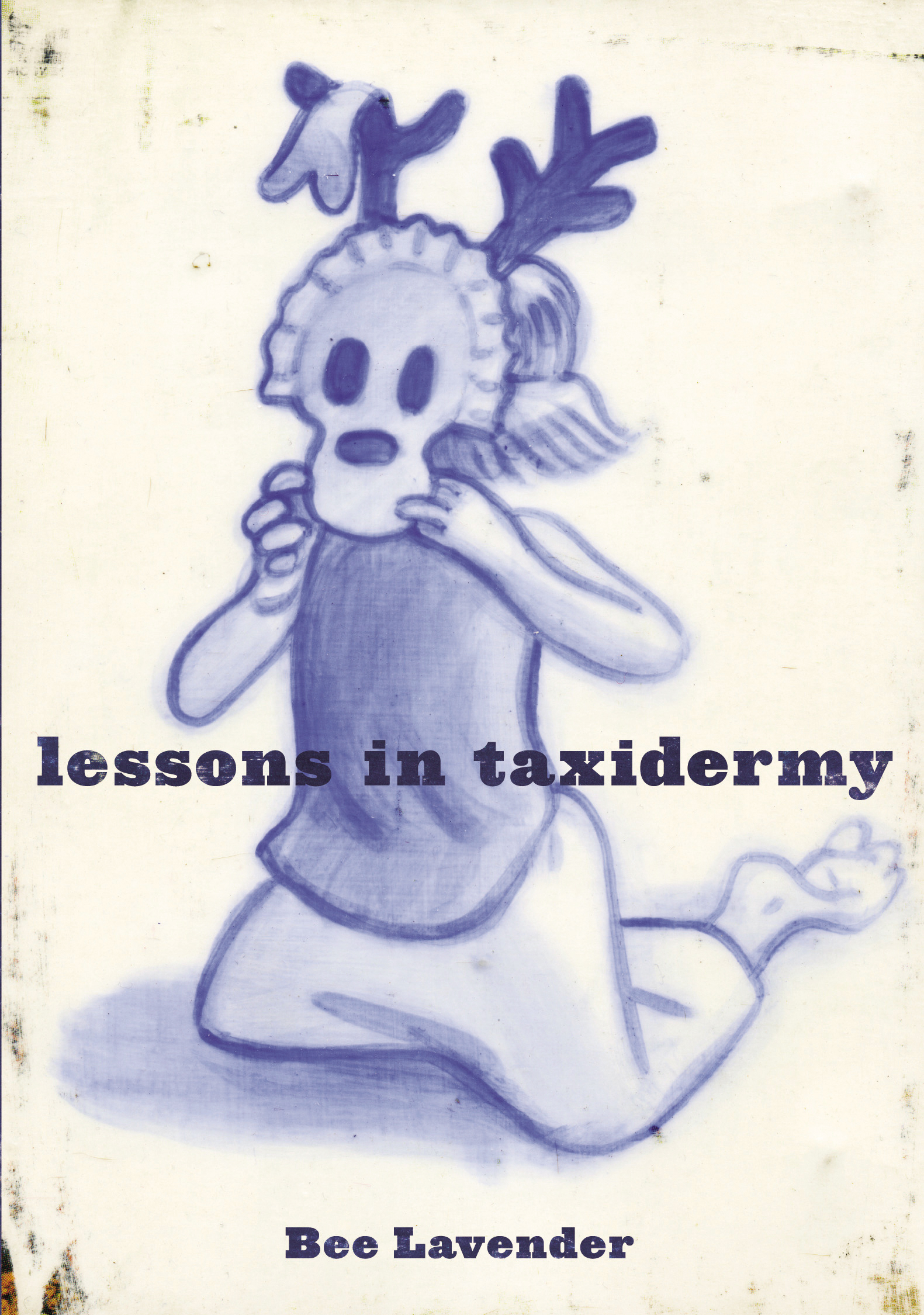

Cover illustration by Gabriel Liston

Book design by Pirate Signal International

The lyrics, Our lives shall not be sweated from birth until life closes / Hearts starve as well as bodies; give us bread, but give us roses, which appear on page 133, are from the song Bread and Roses by James Oppenheim, words, and Martha Coleman, music (Sing Out!, Volume 25, 1976).

The lyrics, All the agonies you suffer / You can end with one good whack / Stiffen up, you ornry duffer / And dump the bosses off your back! which appear on page 135, are from the song Dump the Bosses off Your Back by Utah Phillips.

ISBN-13: 978-1888451-79-5

eISBN-13: 978-1617750-52-6

ISBN-10: 1-888451-79-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2004115618

All rights reserved

First printing

Printed in Canada

Punk Planet Books

4229 N. Honore

Chicago, IL 60613

books@punkplanet.com

www.punkplanetbooks.com

Akashic Books

PO Box 1456

New York, NY 10009

Akashic7@aol.com

www.akashicbooks.com

for my mother

AUTHORS NOTE

Out of respect for the privacy of the people who appear in these pages, certain names and identifying details have been changed or withheld.

Table Of Contents

The wind was blowing across the Puget Sound and into Seattle, bringing with it a tang of salt in the air. I stood in the middle of a neglected garden and inhaled the odor of my childhood, thousands of languorous days and nights next to the water. Growing up, I played on the rocky beaches that hug the divide between the forests and the water, with mountains towering above.

It was midnight and everyone in the house was asleep, but I felt uneasy. Something off-kilter was keeping me awake; a physical sense of apprehension was building in my stomach. I walked down the front steps to the street, skirting the snails that crawl out of the rock wall at night, the stones of the stairs shifting under my feet. One part of me attended to the shadows in alleys, but there was nothing to fear there. Nobody would bother me; nobody would even look twice as I trudged along.

I walked four blocks over a steep hill to a bluff that stands high above industrial flats, a glittering grid of docks and warehouses far below. Standing on a patch of wet grass I looked west across the inlet toward the outline of the Kitsap Peninsula illuminated by the moonlight, about six miles away in geographical terms but requiring either a long ferry ride or a hundred-mile drive around the inlets. The peninsula is more populated now, but when I lived there it was mostly forest with a few small towns and military installations tucked away behind stands of trees. It was too dark to see the Olympic mountain range beyond.

I am descended from one of the first pioneer families that homesteaded land on the peninsula, and most of my relatives still live within thirty miles of the original farm. They work in the shipyard, on the ferries, in gas stations, or in wrecking yards. A few of my cousins have joined the military and traveled the world but they almost always move home again when their tour of duty is over. Growing up in our rural enclave, I was always jealous of their certainty, wounded by their casual convictions. My cousins had advantages; they could work with their hands, walk the fields, move forward with an easy familiarity. They knew exactly where they belonged, and I watched them with a hungry desperation. We grew up in the same place, we were connected by blood and history, but I was different, separate, strange. I looked across the water and sighed. My stomach did not feel better and I turned to walk back home.

Quietly wandering through the house, ignoring the pain, I touched the yellow Formica table in the kitchen for scratches, then checked that my old chipped bowls and plates were stacked correctly, with various colors alternating. The room is host to dozens of pictures of strangers children, small boys of a previous century smiling as they go on pony rides or pose in long forgotten studios, and I stopped at each one, adjusting the frame, wiping dust off the glass. There are no pictures of my family on the walls; the photographs of my own children are tucked away, hundreds of images hidden in boxes, as though it would be unseemly to boast about my great luck in knowing them. Instead there are these other children, rescued from rummage sales and piles of garbage, children presumably once loved by their own mothers but later discarded by uncaring hands. In the hallway I paused to straighten a panoramic print of an army troop standing in orderly rows, ready to depart for the trenches of World War I.

The feeling in my stomach was getting worse. I brushed my teeth, holding the edge of the sink, each upward thrust of the toothbrush a chore. Looking in the mirror I saw a pale face covered with heavy makeup; and then, as though my childhood double vision had been restored, I saw one face superimposed over another, the mask of daily life sliding out of focus as the dreaded ugliness of an earlier time came into view. The face in the mirror had a frowning mouth covered in dark red lipstick to conceal lips that are losing pigment. There were lines across a forehead, but not from agethe lines were there when I was seven, nine, thirteen, twenty, frowning in concentration. Beads of sweat melted the makeup applied to cover ancient facts: scars, or the risk of additional scars. The eyes looking back at me from the mirror were haunted, terrified, no matter what the grown-up self wanted to believe. I saw everything: the past and the present, the solutions and sorrow. I wanted to put my fist through the image in that mirror. Instead I turned away, looked down, found the hairbrush.

It can take twenty minutes to untangle my long unruly hair and sometimes I just tie it in a knot on top of my head. But the party I had attended earlier that night had been in a club, with people smoking and laughing; it was imperative to remove the stench of smoke from my hair. Sitting on the edge of the bathtub I separated sections, lifted a hand, and started to yank a wooden brush through the bramble.

At that precise moment I was undone by a formidable, ghastly pain radiating outward from the guts protected by my rib cage. This was not indigestion, food poisoning, or a virus; there was something seriously wrong. I gasped and doubled over, dropping the brush. No, this was impossible. It could not be happening.

I didnt want to disturb my sleeping family; I didnt want to cause any kind of scene. Im tough, capable of withstanding any sort of crisis. I do not need anyone to look after me, take care of me, cosset and soothe. The people who live in this house are my companions, not my caretakers.

Creeping into the bedroom, I pulled the shade against the light from a neighbors television shining through plate glass windows, lying down on top of the covers fully dressed, trying not to shift or twitch, but the pain intensified. After an hour of tormented stillness I stood up, moving unsteadily, and walked to the bathroom. I sat on the floor and pressed my forehead against the green tiled wall. Then the vomiting began.

The pain across my rib cage turned into a firestorm so overpowering I could barely breathe. It hurt to lie down. It hurt to sit up. Wiping my mouth with a washcloth, I wanted my mother, wanted to be a little child again, safe in her arms, face pressed against a strong shoulder.

Next page