Also by the same author:

From Past to Future Life

Solomoni; Times and Tales from Solomon Islands

Communicable Diseases; a Global Perspective

Copyright 2013 Roger Webber

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park

Kibworth Beauchamp

Leicestershire LE8 0RX, UK

Tel: (+44) 116 279 2299

Fax: (+44) 116 279 2277

Email:

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

ISBN 978-1783061-211

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in Perpetua by Troubador Publishing Ltd

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

For

Hugh Fredrick Webber

(1911-1957)

C OVER

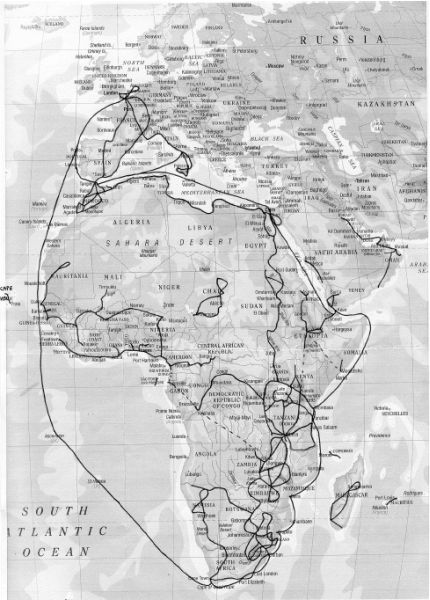

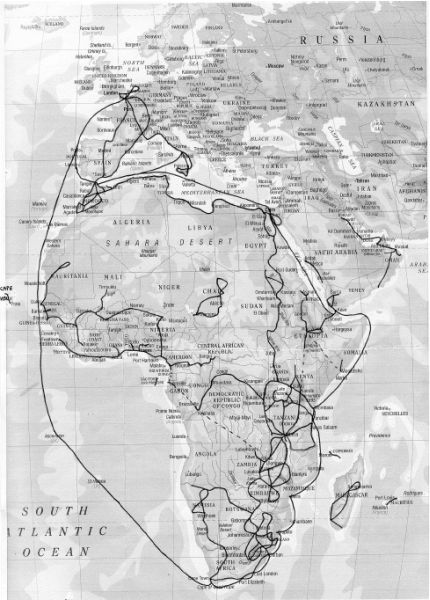

M APS

F IGURES

War had been declared and Britain was in a state of uncertainty. While in mainland Europe one country after another fell to the onslaught of the German fighting machine, we had bravely extricated the remnants of our army from Dunkerque and waited for the inevitable. We knew we were next but there was a strange sense of euphoria as the summer months of 1940 went by. They were glorious and it was hard to realise there was a war on, when the attacks started. The Luftwaffe bombed airfields in an effort to destroy the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the first stage of their intended invasion. The Battle of Britain was underway. It reached its culmination in mid-September when, due to the heroic action of the few, such heavy losses were inflicted on the Germans that they realised they could not defeat the RAF. This however led them to unleash a new reign of terror.

More as a propaganda raid than with any intention to inflict much damage, bomber command made a raid on Berlin to demonstrate that we could hit back. This so infuriated Hitler that he changed strategy from attacking airfields to bombing London. As he had said in one of his propaganda speeches, For every bomb they drop on us, we will drop a hundred on them. The Blitz had started, and my heavily pregnant mother had to contend with this as my time for delivery came ever closer. On the night of the 23rd of September there was an incendiary attack, and it was probably those thick tiles that were a feature of the houses in the Harrow part of north London, that saved the nursing home from destruction. The incendiary bounced off the roof, so I made it into the world without a baptism of fire.

It was the war that took my father to Africa, and when it was all over, where he decided he wanted to work. From being a schoolmaster in various parts of southern England, the prospect of a new life in Africa became an alternative attraction. He returned to Britain just long enough to tell my mother where he was going and set off once more for this land in the south. He had been posted to Zanzibar so not knowing where it was he bought a map and showing it to my bemused mother, pointed to this island off the coast of East Africa. Neither of them knew anything about the place and in a war-ravaged Britain, there was little chance of finding out any more.

I can almost hear my mother saying to him, What on earth are we going there for? Why can you not get a job here?

The reality was that people who had done war service had made a double sacrifice: firstly fighting for their country and then losing out in the job market to those who had stayed behind. He had tried to get work, but in frustration had joined the colonial service. It was hardly a calculated decision but one that was to change all our lives.

Zanzibar was to be a profound influence on my early life. It became home to me; this was the world I knew and the place I would always be naturally drawn back to. As we were soon to find out Zanzibar was one of those special places, with even the name evoking ideas of an enchanted land. I was fortunate to live there at a time when it was a peaceful autonomous island, spared from the revolution that later tore it apart, ignobly joining it to what was Tanganyika, to form Tanzania. There was no need for this union; it had everything it needed and at that time rivalled the mainland in importance.

Zanzibar was the start of my travels so the first part is a record of those times, set in a historical context. Then it was to Tanzania that I returned to work, to a unified country that now incorporated Zanzibar. This was my base from which I travelled far and wide in this intriguing continent.

Rather than thank individuals for helping me with this book, of which there are many, it is more the collective experience of a wonderful people and their beautiful island. When it was an island nation it was the island people that had been such an influence on my life, but even as they subsequently took their part in a larger country, it was still the people of Zanzibar that always seemed to shine through. They showed great respect for my father and what he had done for them and just to mention his name was enough to open any door. Many years later my professor and a group of visiting doctors from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine were marooned on Pemba trying to get a flight out. He casually remarked to one of the ministers who had commandeered the plane that a member of his staff was the son of Mr Webber. Suddenly seats were made available and they were all able to leave. It was this respect and good nature that I so admired in them and which I wish to acknowledge.

Many good books have been written about Zanzibar and the eastern part of Africa, some of which I have used as source material and are listed at the end. I am most grateful to all of their authors for adding greatly to my knowledge of Zanzibar and the rest of Africa.

As happened with so many children, my father had gone to war and I didnt know what he was like. I knew I had a father, but I had no memory of what he looked like and even less could I comprehend where he might be. He was in some remote land that I could not appreciate, when quite unexpectedly I received a parcel for my sixth birthday, which helped put things into place. With much excitement, the parcel was unwrapped to reveal a black ebony elephant, sent from Africa. This was where my father was and soon we would be going there as well.

In 1946, the war was barely over and everything was far from normal. Rationing was still in place and travelling around the country was difficult. International transport was even more of a problem and the only way we could go to East Africa was on a converted troop ship.

The MV Georgic, with its huge cabins for accommodating troops was hardly suitable for families that had just come through a war, but this was all there was available. They put all the children in one cabin and the mothers in another, which was a disastrous arrangement. Separating families, when they most needed to be together, was one of the most ill-conceived ideas of the wartime government, and even now when the war was over, it still persisted. So almost as revenge, the children of this immensely large cabin banded together to defy any intrusion into their domain. The favoured weapon was the water bomb, made by folding a piece of paper into a cube, filled with water and then thrown at the enemy. The noise in our cabin was normally so great that a steward would have to come in to shut us up, but he would be greeted by a barrage of water bombs. The poor man retired soaked and intimidated; we might have been young, but together we were a formidable force.

Next page