First published by Pitch Publishing, 2016

Pitch Publishing

A2 Yeoman Gate

Yeoman Way

Durrington

BN13 3QZ

www.pitchpublishing.co.uk

Rod Gilmour, 2016

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the Publisher.

A CIP catalogue record is available for this book from the British Library

Print ISBN 978-1-78531-218-2

eBook ISBN 978-1-78531-278-6

--

Ebook Conversion by www.eBookPartnership.com

Contents

Acknowledgements

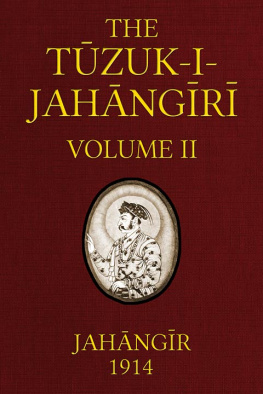

The authors would like to thank the following for their invaluable help in this project: Jahangir Khan for the interview. Ross Norman, Geoff Hunt, Hiddy Jahan, Rahmat Khan, Brian Townsend, Andrew Shelley, Howard Harding/squashinfo.com, Richard Eaton, James Zug, Ian McKenzie, Steven Line/squashpics.com, Rob Dinerman, Danny Lee, Adrian Wizard Davies, Phil Kenyon, Gawain Briars, Rob Owen, Chris Dittmar, Maqsood Ahmed, Bradley Hindle, Ian Robinson, Graham Dixon, Malcolm Willstrop, Allistair McCaw, Tony Griffin, Lisa Opie and Adam Donoghue.

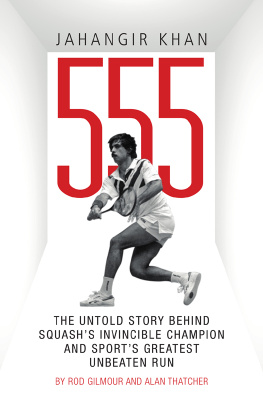

Introduction

J UST imagine if Jahangir Khan had been a boxer, or a golfer. Jahangir was more successful than both Muhammad Ali and Tiger Woods, but his chosen sport was squash. The game is not unlike the other two. It mirrors boxing for the sheer gladiatorial brutality of the big matches, where two protagonists are locked inside a glass box, trying to inflict maximum physical damage on each other, and simulating a golfers skills with the need to master the technique required in a variety of swing patterns that can make the ball go where you want it to (although in squash you are hitting a ball often moving at astonishing speeds and obviously dont have the luxury of the time afforded golfers to tee up their shots).

Squash players, of course, do not gain the phenomenal financial rewards accrued by the worlds top golfers, boxers, soccer players and the star names in a variety of other sports, ones who attract a mass of television coverage and generate millions of dollars from the sponsorship that goes with it.

Having said that, Jahangir did very nicely, thank you, for a squash player. Despite the limited financial returns available to the most successful players of his sport, his global domination of squash meant that several companies were willing to parade his name on rackets, shoes and clothing in product endorsements on both sides of the Atlantic.

Those fees may fade in comparison to the worlds most lucrative sports, but Jahangir was one of the greatest athletes the world has ever seen. Sports fans of a certain age will know his name, but few will appreciate the impact Jahangir had on squash.

Grainy television footage from most of Jahangirs successes rarely see the light of day. There were a host of rights holders during squashs boom time in the Eighties the BBC regularly screened major tournaments live but the current world tour body, the Professional Squash Association (PSA), doesnt hold rights to the archive of Jahangirs stellar five-year period at the start of the decade.

For that, we must turn to YouTube. With squash struggling to really shine in the public spotlight in the modern era, despite the PSA working tirelessly to make the excitement and drama of top-class squash translate to the small screen with its high-definition coverage, Jahangirs name has largely been consigned to history and the internet.

At the time, though, he was incredibly popular. Adored in Pakistan and revered across the globe by all those connected with the game, Jahangir changed the landscape of squash. He was on a different plateau to every professional of the time.

Little wonder, then, that he was to meet Ali several times, sharing championship successes together. There is a famous image from a meeting at newspaper offices in Saudi Arabia of Ali ducking and weaving, and Jahangir swatting a racket at the great boxer. It paints a powerful picture of the Pakistanis status at the time.

Newspapers covered his rise and sports editors gave squash decent space when big tournaments were being reported on.

For that we can be thankful, too. The British Library newspaper archives proved a welcome tonic when compared to the treatment handed out to the sport in the current media landscape.

In November 1986, as Jahangir moved towards six years unbeaten in the sport no one knew then exactly how many matches he was unbeaten, only that it was in the hundreds the worlds best players travelled to Toulouse for the mens world championship.

In the same week, tabloids and broadsheets were reporting on Scot Alex Fergusons new role as Manchester United manager; Allan Border, the Australian cricket captain, was dismissing the soon-to-be triumphant England side ahead of the first Ashes Test in Brisbane; and, later in the month, Mike Tyson was to become the youngest world heavyweight boxing champion, aged 20 years, four months and 22 days.

Squash had rightful billing alongside these stories and that is down to Jahangirs status even if his continued winning hardly created dynamic subplots for the media to write about. Toulouse changed all that. So it is, in the 30th anniversary year of Jahangirs unprecedented winning streak, that we can now bring his unique career to life: from two hernia operations as a young boy to the sports first superstar and winner of multiple world and British Open crowns.

We are thankful to those who contributed to his story, to those former players who were fortunate, or unfortunate enough, to play against him during the Pakistanis grand heights. These were skilled professionals, consigned to regular beatings.

Jahangirs career blossomed as the world tour took shape. He was there at the beginning of a global circuit as the Eighties dawned. It was an era of great change for the sport. From four walls of traditional plaster to the introduction of see-through courts. From small, wooden rackets to the new, bigger graphite models. Plus changes in the scoring, designed to make the sport more attractive to television. With each passing year, Jahangir adapted to the changes and still conquered.

Jahangirs peers describe in detail too the aura behind him and how difficult it was to play against the Pakistani when those glass court doors were closed in the fish tank. They were on their own then and it was up to them to save face. Many left the court drained, unable to speak and with few points to show for their efforts.

His gentlemanly conduct and unbeaten streak continued unabated, as bludgeoning success in the early Eighties turned him into a one-man brand marketing machine. Jahangir endorsed countless products and he became the sports first and only squash millionaire. Tellingly, his quiet, humble manner remained the same.

Some may differ but many players of the time paint Jahangir, or JK as he is also known by friends and former professionals throughout the book, as the best squash player of all time. Perhaps sportsperson, too. His record, his story and the history he created go some way towards reflecting this.