I have lived in far countries, abroad, or in the agitating world at home so that almost all I have written has been mere passionpassion, it is true, of different kinds, but always passion: for my indifference was a kind of passion, the result of experience, and not the philosophy of nature.

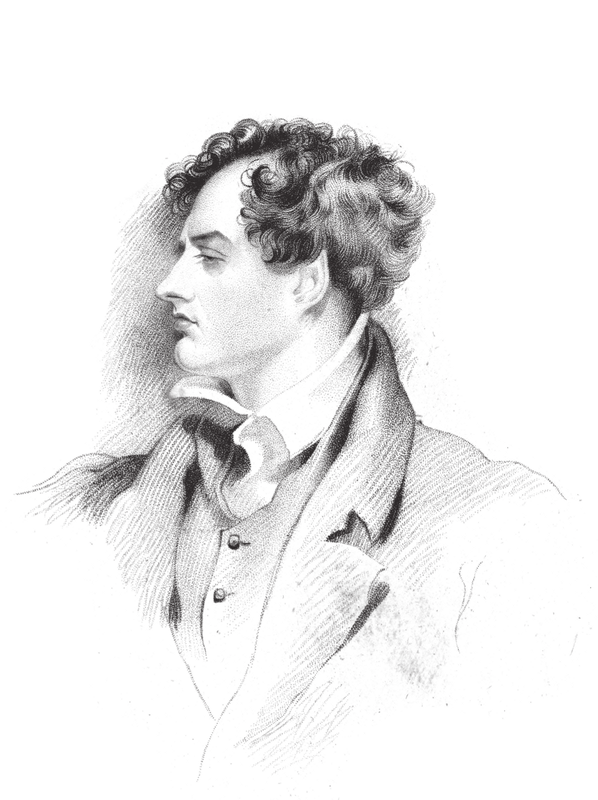

BYRON

T hree years after Byrons death, the Contessa Teresa Guicciolithe object of the poets last, longest and perhaps deepest attachmentwrote to Barry that his letters to her were a treasure of goodness, affection and genius, which for a hundred reasons I cannot now make public.

Since then seventy-five years have passed. And now, owing to the courtesy of Count Carlo Gamba, Teresas great-nephew,to whom she left her villa at Settimello and all its contentsTeresas papers and treasures have at last come to light. The treasuresByrons relics, as she called themstill lie in the carved mahogany box in which Teresa kept them. There is the locket containing her hair, and hung on a chain of her hair, which Byron was wearing when he died, and which Augusta Leigh sent back to her; there is another locket, containing Byrons hair, which he gave to Teresa when he sailed for Greece. There, too, carefully wrapped up by Teresa, with an inscription in her writing, lies a curious, moving assortment of objects: a piece of the wall-hangings of the room in Palazzo Gamba where Byron used to visit Teresa, Byrons handkerchief and a fragment of one of his shirts,and a crumbling rose-leaf, with the branch of a tree and a small acorn, from Newstead Abbey. Finally there is a fat little volume bound in purple plush: the copy of Corinne in which he wrote his famous love-letter to Teresa in Bologna.

The papers in this collection have proved to be as exciting and interesting a hoard as the most exacting biographer could hope for. They include, not only 149 of Byrons love-letters, mostly in Italian, to Teresa, and some of her answers, but Teresas Vie de Lord Byron,her unpublished account of his life in Italy, which she wrote in her old age and thought too intimate to be published during her lifetime. In addition there are the documents of the Guiccioli lawsuits, containing a complete account of the complicated circumstances which led to Teresas separation from her husband, and there are Pietro Gambas letters to his sister from Greece, besides many other letters to her from Shelley, Lady Blessington, Lamartine, John Murray and others. In short, we have at lastwith all the gaps filled in by information at which, until now, it was only possible to guessthe full story of Byron and Teresa Guiccioli.

It is notthis must be admitteda wholly pleasant story, and it is one which it is difficult to tell impartially. There is a temptation to take sides: either to portray Byron as an unscrupulous cad, seducing a pretty young woman who had fallen desperately in love with him, laughing at her in his letters to his friends, and gradually cooling off, to leave her abandoned and alone; or, alternatively, to depict Teresa as a designing minx, who, tired of her elderly husband and her dreary provincial life, flung herself at Byrons head until he was perforce obliged to turn a fugitive love-affair into a romance in the Anglo fashion. Or else the whole affair could be presented in the manner of the Goldonian Comedywith the audiences sympathy focused on the two lovers, and with Count Guiccioli (the avaricious, calculating husband) as the villain, Fanny Silvestrini as the obliging confidante, Count Ruggero as the noble father, and Pietro as the young gallant. Even the minor parts could be allottedthe venal priest, the maid, the Moorish page-boy,and, in the pine-forest of Ravenna, the chorus of conspirators.

But now, with these new papers before us, none of these simplified versions will do. The actors too often speak out of partand the story that emerges is too full of discrepancies and inconsistencies. Besides, there are a few minor points which, to my mind, even now remain obscure. I am still not quite certain about the motives of Count Guiccioli; I do not know what Byron meant by his letter on page ; I am not always sure when Teresa is, or is not, speaking the truth. The reader, too, must guess and draw his own conclusions. I have merely attempted to fill in the backgroundto complete the story with passages from Byrons other letters at the time or from the accounts of his contemporaries, and to give such information as seemed necessary about the people, the setting and the local history. But I have carefully refrained from adding any imaginary details or touches of local colour: any information that the book contains can be confirmed by some record.

For it is the papers themselvesthe scribbled, passionate love-letters, the painstaking police reports, the formal ecclesiastical decrees, the gossip of observant contemporariesthat must tell the story. They provide a singularly intimate and unvarnished account of the daily life of this little group of people, 130 years ago. Their passionate protestations, their jokes, their retractions and lies, their plans and disappointments, all that constituted the most private aspect of their livesthese are now laid before us in merciless detail. Now, after more than a century, we can follow the negro page carrying Teresas notes to Byron up the staircase of Palazzo Guiccioli, or stand with the groom Morelli, watching by the front door to warn the lovers of the Counts return. We can look out from Teresas balcony in Palazzo Lanfranchi in the moonlightand Mary Shelleys carriage is clattering up the Lungarno, and she is calling out, Sapete alcuna cosa di Shelley? We are in Teresas sitting-room in Casa Saluzzo, and Byron comes in, very cross, and gives her an unpleasant letter for Maryand when he has gone out again, she turns it over and over and peers at the seal, and does not dare to look inside. We are with Byronbored and flat and sadon the Hercules in Leghorn harbour, and Pietro Gamba is standing over him with a pen, to make him write to Teresa his last meagre note of farewell.

Here is the story of two passionate, unstable human beingsone of them a great poet, and a very odd manthe other a young woman of quite exceptional vitality and strength of will. They loved each other; they quarrelled; they trampled ruthlessly on whatever stood in their way. Of the two of them it was, curiously enough, Byron who occasionally played the moralist. Teresa, for all her convent-school training, appears to have been unaware throughout that any moral problem was involved. They committed themselves, and they drew back again. One of them was often disloyal, the other sometimes insincere. Each of them in turnByron in Ravenna, Teresa in the English circle in Pisahad to conform, for the others sake, to the ways of a bewildering and alien society. As time wore on, one of them became plaintive, the other exasperated. But at all times they were quite extraordinarily alive. They galvanized everyone who came near them. In these letters, they are living still.

Moreover, these papers light up a facet of Byrons character which, until now, has been unfamiliar: they show him living in an Italian setting. And the extent to which these new surroundings affected and changed him appears in a manner which is not only interesting, but sometimes disconcerting.

Byron himself, indeed, tried to tell his friends about it: Now I have lived among the Italians,not Florenced