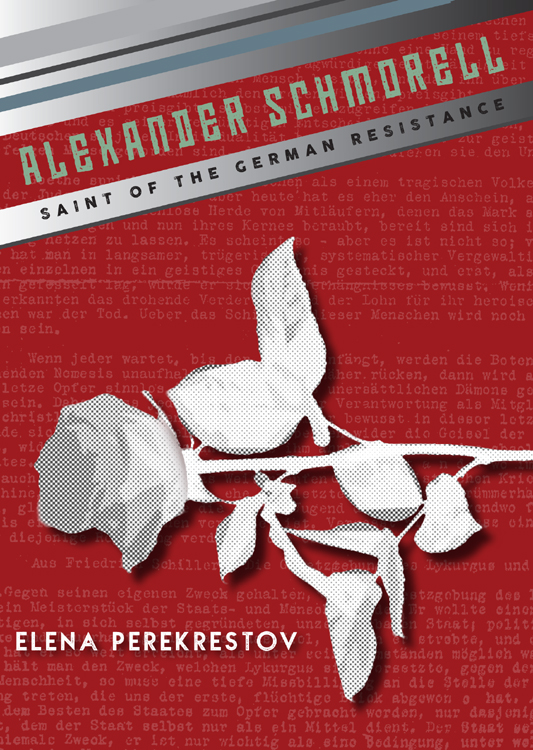

Printed with the blessing of His Eminence, Metropolitan Hilarion First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia

Alexander Schmorell: Saint of the German Resistance

2017 Elena Perekrestov

ISBN: 978-0-88465-421-6 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-0-88465-456-8 (ePub)

ISBN: 978-0-88465-457-5 (Mobipocket)

Library of Congress Control Number 2016962428

Cover Design: James Bozeman

Alexander Schmorells letters from prison, The Munich Student Group from DYING WE LIVE by Hellmut Gollwitzer, are copyright 1956 by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Scripture passages taken from the New King James Version.

Copyright 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission.

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America

He endured hatred who did not know how to hate; he was slain impiously who while dying did not fight back.

St Cyprian of Carthage on Abel, the first martyr

I leave this life with the knowledge that I have served my deepest conviction and the truth.

Alexander Schmorell

Letter to his parents on the day of his execution

July 13, 1943

CHAPTER 1

Resisting the Dictatorship of Evil

O ur twentieth century, observed Solzhenitsyn in his Nobel Lecture (1970), has turned out to be more cruel than those preceding it. It is not surprising, therefore, that the twentieth century contributed a great multitude of saints to the calendar of the Orthodox Church and that the majority of these saints were martyrs. Among these is a radiant soul whose story is as unique as it is inspiringSt Alexander of Munich, whose short but vibrant life came to a martyric end in 1943.

The fact that these twentieth-century martyrs lived at a time so close to ours is both a blessing and a challenge. On the one hand, the availability of letters, diaries, reminiscences, and official documents allows us to form a picture of a persons disposition and the circumstances of his or her life and death that is much more detailed and comprehensive than we can reconstruct for saints of earlier ages. On the other hand, we are challenged to come to terms with the fact that these saints are people who were much like ourselves, who lived lives so much like ours, and dressed in the familiar attire of the twentieth century instead of the robes more commonly seen in the saints depicted on our icons.

The perplexity that this evokes in us is echoed by a friend of St Alexander, who commented on the fact of his glorification by the Russian Orthodox Church in 2012 by saying, He would have laughed out loud if hed known. He wasnt a sainthe was just a normal person.

Just a normal person. How is it that this normal, life-loving young man chose to embark on a course of action that he knew would put his life in jeopardy, and then ultimately came to sacrifice his life? What prompted and, more important, what enabled him, together with a group of close friends (the circle of young students at the University of Munich known to the world now as the White Rose), to bear witness as profoundly believing Christians to their convictions and culture, which were being systematically and brutally annihilated by the Nazis? What gave Alexander and his friends the strength to exhort their fellow Germans to join them in opposing the Nazi regime, which had opposed itself to the Divine Order, and, in so doing, to be among the first to make the voice of resistance audible in Hitlers Germany?

Andcan a normal, ordinary person indeed be a saint?

Before attempting to answer these questions, we must first recall the backdrop against which the story of the noble and courageous quest of Alexander Schmorell and his circle of friends unfolded.

With Adolph Hitlers rise to power and subsequent imposition of National Socialism throughout all spheres of life in Germany, some people felt compelled (many of them by their Christian faith) to oppose the incursions into their lives and values of a system that sought to control, dominate, and ultimately destroy everything in which they believed. Germany had become a place where one could no longer speak as ones heart and mind dictated; in which wrong could no longer be called wrong, falsehood could no longer be called falsehood.

Although resistance to the Nazi regime within Germany was not a mass movement, opponents of National Socialism included people from all walks of life and of different convictions: monarchists, Communists, Protestant and Catholic clergy, farmers, aristocrats, students, and army generals. Resistance was based on political, moral, and religious principles.

For some, opposition meant an inner aversion and rejection of Nazism, which could spill over into overt gestures: using Grss Gott (may God greet you), the customary south German greeting, instead of the prescribed Heil Hitler, or criticism of the Fhrer voiced within a close circle of friends. Others were moved to express their opposition to the regime in a more consistent and definitive manner. Such resistance ranged from the actions of isolated individuals who defied Nazi laws and policies, and acted according to their consciences instead, to intricate conspiracies such as the unsuccessful coup dtat and attempt to assassinate Hitler on July 20, 1944, known as Operation Valkyrie.

In both passive and active resistance to Nazism, Christian ideals and idealism played a significant role.

Measures to subordinate and then eradicate Christianity included the closure of monasteries, convents, and religious schools; prohibitions against pilgrimages and religious processions; hate and slur campaigns against clergymen; arrests, incarceration, and execution of religious opponents of the regime; along with attempts to bring the Protestant and Roman Catholic Churches under the authority and influence of the state and to institute a Nazi-controlled Protestant state church, known colloquially as the Reich Church.

As part of their program to root out the influence of Christianity, the Nazis took steps to establish a new cult, a new form (in reality, a parody) of Christianity, called Positive Christianity. This was to be a more heroic religion than Christianity, with its enfeebling preoccupation with sin, mercy, and condescension for the weak. It would be purged of its Old Testament (Jewish) elements, just as German society would be purged of Jews. Christ was believed to be not a Semite, but an Aryan hero.

Alternativeessentially neopaganceremonies for weddings and burials were developed. Christmas festivities were transformed into celebrations of the winter solstice. The swastika (in GermanHakenkreuz, meaning hooked, broken, or twisted cross) was forcibly substituted for the crucifix and religious images in schools and public places.