I dedicate this book to my beloved city of Liverpool.

CONTENTS

Postscript:

Appendix:

IN 1979, AS I was embarking on my Beatles biography Shout! , I asked Bill Harry, John Lennons fellow art student and founder of Mersey Beat , to suggest interviewees who might give me a fresh perspective on a story everyone thought they knew. Why dont you talk to Joe Flannery, he replied. A couple of weeks later, I knocked on the front door of a neat 1920s house in Aigburth, Liverpool, and was greeted by a tall, quietly spoken man whose name appeared in none of the Beatles reference books then available. Biographers, especially in the rock music area, depend greatly on luck: that was one of my luckiest days ever.

Joe Flannerys perspective was fresh indeed. His cabinet-maker father, Christopher, used to supply custom-built chests-of-drawers to Harry Epstein, the Liverpool furniture dealer, whose older son, Brian, would one day manage the most beloved pop band of all time. Joe had met Brian and already fallen more than a little in love with him when they were children. Both grew up to be gay in an era when homosexuality was outlawed in Britain and particularly anathematised in macho northern cities like Liverpool. With Joe, Brian had his only happy, stable relationship in a love life otherwise shadowed by fear, guilt, violence and disgrace.

The two lost touch for a few years, then met up again in 1962, by which time Brian was running the record department at his familys central Liverpool electrical store. As a side-line, he had decided to manage a black leather-clad beat group called the Beatles who, he insisted to general mockery would one day be bigger than Elvis. Dapper, well-spoken Brian, however, had no idea how to talk to the tough Merseyside dance promoters who were the Beatles main employers. So Joe volunteered to handle their bookings, and also made his house a base-camp for them after late-night gigs when it was too late to return to their respective homes. As a result, he could tell me Beatles stories that no one had ever heard before: of John (who always called him Flo Jannery) lying on the rug in front of his living-room fire, turning out endless drawings and poems; of Paul, asking him for guidance on social etiquette rather like Pip in Dickens Great Expectations ; of giving George driving lessons in his car in the dawn hours while the others were asleep.

He also proved fascinatingly authoritative about the bands mythic pre-Epstein period, with their pre-Ringo drummer Pete Best, playing drunken all-night shows among the strip-clubs and mud-wrestling pits of Hamburgs red-light district, the Reeperbahn. Hed later gone out to Hamburg himself, acting as a kind of den-mother to other Liverpool bands like Lee Curtis and the All Stars, whose vocalist was his younger brother. Under his tutelage, I spent a week on the Reeperbahn, drinking the same beer and eating the same German hotdogs that the Beatles once had, and popping the same uppers to be able to stay awake all night.

Brian had died of a drink-and-drugs overdose in 1967 prefiguring the Beatles drawn-out, messy collapse but to one person, at least, hed never been forgotten. Each year on his birthday, Liverpools Long Lane synagogue gave Catholic Joe special permission to break with Jewish custom and place flowers on his grave.

As we became friends, Joe told me about the hellishness of being gay in 1950s Liverpool, even if one didnt take the horrendous risks Brian did. He related blood-chilling stories of the queer-bashing gangs that used to roam the streets; of the eminent citizens who preyed on gay young men with impunity in the backs of their Rolls-Royces; of the homophobia of police, the judicial system and, worst of all, ones own family. His father never came to terms with Joes sexuality though his wonderful, doughty mother, Agnes, shielded him from the worst of Christophers brutality. At one heartbreaking moment, Joe tried to express his love for his father by buying him a record, Eddie Calverts O mein Papa . O mein Papa, the lyric runs, to me he was so wonderful/O Mein papa, to me he was so good ... Christopher took one look at the old-fashioned shellac disc, then broke it over Joes head.

There were other, happier stories, too, from the long ages before the world had heard of John, Paul, George and Ringo: of growing up in the next street to the crooner Frankie Vaughan; of working as a waiter at Liverpools Adelphi Hotel in its glory days, when Joe often found himself serving Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother: of his latter long, happy relationship with a sweet man named Kenny Meek, and his artists management partnership with Brian Epsteins younger brother, Clive, who bore just enough of a resemblance to Brian to ensure that Joes love never died.

There was the phone conversation he had with John Lennon in New York, shortly before the fateful night of 8 December 1980, when John talked about making a triumphal return to Liverpool and asked Flo Jannery to hire the QE2 to bring him up the Mersey. And there was always the Flannery humour, permeating even moments of greatest stress or sadness. After Johns murder, he wrote a tribute song entitled Much-Missed Man , which was to be recorded in Liverpool by one of his new young protgs, Phil Boardman. On the day of the session, typically, Joe drove to the studio with a red carnation for Phils buttonhole. As he told me at the time: You know how much my religion means to me but if a Catholic nun had been thumbing a lift into town, I wouldnt have stopped because itd have meant moving that carnation Id arranged so carefully on the seat beside me.

For years, Ive been urging this dear, modest man to claim his rightful niche in pop music with a book about the Beatles but not all about the Beatles. Im delighted hes now done so.

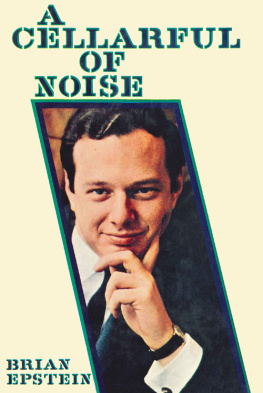

IT ISNT AN exaggeration to say that without Brian Epstein, the Beatles we know and love today wouldnt exist. The former Beatles manager helped shape the musical landscape of the city, guiding the Fab Four from being a popular cellar act to global superstardom.

As a city, we want to make sure the legacy of one of Liverpools greatest sons continues, and it was a real honour when Brians family gave us permission to rename the Neptune Theatre to The Epstein signalling a new chapter for the refurbished music venue which will hopefully discover the next generation of outstanding musical talent in the city.

This book by Joe Flannery sheds new light on the Epstein story, providing some previously unheard anecdotes about the man referred to as the Prince of Pop a man who changed the face of the music industry forever and, as a result, put Liverpool firmly on the map as a city overflowing with culture and creativity.

THE FLANNERYS CAME to Liverpool, via Cornwall, from Ireland. They were peasants from the rural area just west of Dublin and came to England to escape the potato famine of 1845. Land was in short supply in Ireland at this time and this family, like many others, grew what they could to sustain themselves on insufficient and meagre soil. My great-grandfather was one of nine children and his parents originally had about 2 acres of farmland; however, they had decided to let 1 acre of it go because a good potato crop could sustain even a large family on only 1 acre. There would always be spuds, it seemed, and it didnt give the impression that it was worth the rent to farm 2 acres. Potatoes were the staple crop in Ireland at this time and it has been estimated that at least 4 million out of a total population of 8.5 million could, like the Flannerys, afford little else. But by the summer of 1845 potato blight had already appeared in England and by the autumn it had spread to Ireland; catastrophe ensued. Thousands starved to death, and the Flannerys gave up all they had which was probably very little in the first place and, along with countless others, decided to leave Ireland once and for all. The rural working classes in Ireland were faced with a very simple choice: stay and starve or leave and begin again. The Flannery family chose the latter and after initially trying their luck in the south-west of England in tin mining and fishing, they eventually ended up, along with many others of their kind, in the seaport of Liverpool.

Next page