P.O. Box 1588

Copyright 2002 by NewSouth, Inc. Foreword copyright 2002 by William L. Andrews. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by NewSouth Books, a division of NewSouth, Inc., Montgomery, Alabama.

by William L. Andrews

The autobiographical narratives of former slaves comprise one of the most influential and inspiring traditions in all of American literature. We know not where one who wished to write a modern Odyssey could find a better subject than in the adventures of a fugitive slave, wrote one literary critic in 1849 after reviewing such classic antebellum texts as Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (1845) and Narrative of William W. Brown, A Fugitive Slave (1847), both of which were international best-sellers. The narratives of famous fugitives from bondage, epitomized by Douglass, William Wells Brown, Henry Box Brown, who escaped from slavery by shipping himself in a wooden box to freedom, and Harriet Jacobs, who hid for seven years in a crawl space in her grandmothers attic before her flight, thrilled readers in the pre-Civil War era and continue to fascinate us today, as evidenced by the many current reprints of the autobiographies of these heroic individuals.

Scholars recognize that the antebellum slave narrative tradition provides the grounding, and often the actual subject matter, of some of the most widely read novels in American history, including Harriet Beecher Stowes Uncle Toms Cabin (1852), Mark Twains Huckleberry Finn (1883), William Styrons The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967), and Toni Morrisons Beloved (1987). Yet knowledge and appreciation of the African American slave narrative remains far from complete, primarily because so little attention has been paid to the many first-person narratives of slavery published after the formal abolition of slavery in the United States in 1865.

Few realize that almost as many narratives by former slaves were published after the Civil War as appeared before it. Part of the reason for the eclipse of the post-Civil War slave narrative, with the exception of Booker T. Washingtons Up From Slavery (1901), lies in the fact that, unlike Up From Slavery , the majority of slave narratives after 1865 were published by the people who wrote them, not by commercial publishing houses, religious denominations, or reform societies. Almost all of the famous antebellum slave narrators had the backing of antislavery societies and other reformers who, in the mid-nineteenth century, commanded various publishing enterprises that enabled them to advertise and circulate books and publicize the comings and goings of notables like Douglass, Wells Brown, and Box Brown both at home and abroad.

By contrast, very few authors of slave narratives after 1865 had access to the financial resources and the ready-made audiences that black autobiographers could attract before slaverys abolition. Once slavery was gone, stories about human bondage did not move Americas reading class as they had previously. In fact, by the 1880s the New Souths plantation school of fiction writers had so sanitized and sentimentalized the Old Souths peculiar institution that some critics wondered if northern readers, enchanted by the myth of the plantation as a realm of beneficent masters and grateful slaves, had forgotten what the war had been all about. By 1892, when Frederick Douglass saw the last version of his autobiography into print, his Boston publisher informed him that Life and Times of Frederick Douglass had been virtually stillborn, insofar as sales were concerned. If Frederick Douglass himself, backed by a distinguished Boston publishing house, could not interest American readers in his autobiography in the 1890s, what chance did less established, indeed unknown, African Americans who had once been enslaved have of achieving a readership for their stories?

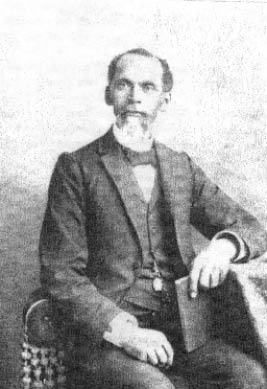

We know little about the origins or the reception of post-Civil War slave narratives such as Thirty Years a Slave; From Bondage to Freedom; The Institution of Slavery As Seen on the Plantation and in the Home of the Planter; Autobiography of Louis Hughes . We also know little about Hughes himself beyond what he tells us in his narrative. Nevertheless, the Autobiography of Louis Hughes deserves to be reread, for the very reason that its author was not a celebrated fugitive from slavery, nor was his memory of slavery one that would have seemed commercial to a white publisher. By paying a Milwaukee printer to publish the Autobiography of Louis Hughes , the former Deep South slave turned Wisconsin businessman was free to write about his experience in the South and the North in his own way. What he wrote identifies Hughes in several ways as more representative of the African American rank-and-file, both before and after slavery, than Douglass or most of the other celebrated fugitive slaves whose antebellum narratives have dominated our understanding of what slavery was like.

Hughess recollections of slavery stem from the point of view of a house slave, a relatively privileged figure who, because he did not have to endure the crushing routine of field work, had both time and opportunity to observe the workings of slavery as it affected virtually everyone on the plantation. Without stinting on the cruelties and mistreatment that he and others suffered at the hands of masters, mistresses, and overseers, Hughes also takes us into areas of slave life where few antebellum narratives go. From Hughes we learn in revealing detail how a slave cabin was furnished, how and what slaves cooked, how they made their clothes, cared for their children, worshiped, celebrated, mourned, and tried to flee their enslavement. While antebellum slave narratives tend to place larger-than-life individuals in the foreground, the better to exalt their heroic individualism, post-Civil War slave narratives like Hughess focus more on slave communities and the means by which they sustained black people until they eventually gained their freedom.

Like most post-Civil War slave narratives, Hughess Autobiography portrays slavery as a kind of crucible that tested his patience, forbearance, and tenacity of purpose but never succeeded in demoralizing him or degrading his sense of self-worth and his desire for freedom. Balancing his relative good fortune as a house servant are his trials at the hands of his ill-tempered, bullying mistress, Mrs. McGee, who seems to take perverse pleasure in daily physical abuse of her personal servants. Living in daily contact with whites gave Hughes the opportunity to portray slave holders with considerable insight. At a time when the plantation school of New South writing was idealizing the Old Souths slaveocracy, Hughes shows us men and women whose pretense of gentility and noblesse oblige masks a pathological self-centeredness that renders them maddeningly, and pathetically, dependent on their own delusions. As the Confederacys prospects worsen, the McGees, more childlike than adult, refuse to see that their power and prerogative to dictate to others are soon to end.