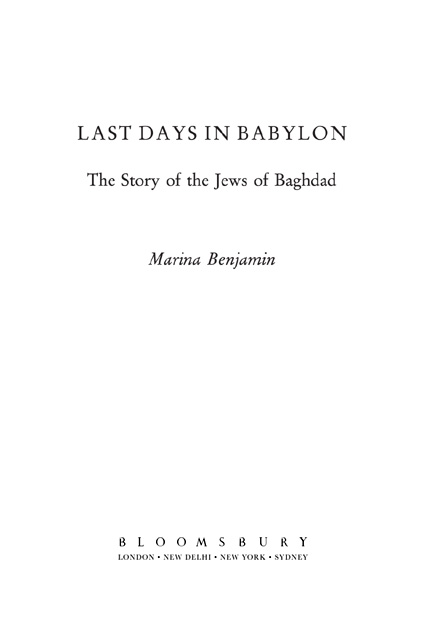

Rocket Dreams

Living at the End of the World

First published in Great Britain 2007

This electronic edition published in 2013 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright 2007 by Marina Benjamin

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN: 978-1-4088-5412-9

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books.

You will find extracts, author interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers

For Marcelle, Bertha and Soren

and in tribute to Regina Sehayek Levy (19051992)

Contents

I am Iraq, my tongue is her heart,

my blood her Euphrates,

my being from her branches formed.

Muhammed Mahdi Al-Jawahiri,

Fi dhikra al Maliki, 1957

At home in London during the cold spring of 2006 I try to summon up images of Baghdad. I want to remember peoples faces and voices, the traditional tilework I admired in their homes, the particular yellow of sunlight bouncing off sandy brick, the delicious skewered meat I ate in restaurants. Its an exercise I go through regularly, as an antidote to the litany of bad news that streams from my television screen.

The news, by now, has a numbing sameness to it. There has been another bombing and more innocent people are dead. Theres footage of cars burning at the roadside. Men in blood-stained clothing help other blood-smeared men to safety. Angry crowds remonstrate with shaven-scalped American soldiers. Women in chadors wail over lost husbands and sons. The city, I reflect for the umpteenth time, is lawless, unrelenting, and I feel a surge of relief that I live where I do, far away from all the violence and turmoil.

Two years earlier I witnessed similar scenes in Baghdad for myself from the safety of a hired car, in the company of a hired guide, and, more often than not, by peering through darkened glass. After the bombing of the Mount Lebanon hotel, an early civilian target of the postwar violence, I was among the crowds of Western journalists who had talked their way past the police cordons to commiserate with the locals and trade theories as to why that particular hotel had been targeted. Too many Westerners stayed there, said one journalist. Too many American Jews said another. No, said a third, the car bomb was intended for the Al Jazeera offices next door.

At the time I had been sickened by the purient flood of onlookers interest (of which I was part, straining as was everyone else for answers that put a rational gloss on the senseless) and by the metallic smell of death, and Id wanted to leave. But now, with my access to such information confined to second-hand relay, I think about how the television cameras do not lie.

First-hand, as on screen, much of Baghdad appears forsaken. It sprawls across a grid of lookalike suburbs built out of dustcoloured concrete with tatty high streets that are permanently snarled with traffic and sporadically patrolled by US tanks. Bomb damage is evident everywhere. Refuse and rubble litter the ground. Police checkpoints, flagged up by double rows of painted oil drums, block off numerous roads, and street fighting is rife after dark. Anywhere, at any time, something might explode.

And yet such images of a scarred city belie the fact that there exists another Baghdad where, even now, it remains possible to capture something of the fabled magic of the ancient city. You wont see Ali Baba thieves spring from earthenware jars brandishing giant scimitars, or stumble across walled gardens concealing tiled fountains. But you can lose yourself in a confusion of twisting streets and fill your lungs with the loamy, musty air of what feels like centuries past. In a small corner of north-eastern Baghdad, known locally as the Old City, all the odds have been defied, and something wondrous of the mythic past has come through the wars intact.

I feel as if Ive known this other Baghdad all my life. A Baghdad of history and cultural romance, consonant with my familys recollections of verdant palm and scented orange groves, of picnics by the Tigris, and sun-baked afternoons spent cooling ones heels indoors, sipping homemade lemonade. Its local characters are colourful, voluble and opinionated. Its politics are as labyrinthine as its streets. Its crumbling buildings creak under the weight of stories untold. It is a Baghdad I believed no longer existed, until I had seen it for myself. And it is the Baghdad that I want to remember beyond the firewall of current carnage, and of seemingly endless and irrevocable change.

The Old City is one of the few places in Baghdad where you wont see American soldiers, since most of the streets are too narrow to support armoured convoys. Western civilians are thin on the ground, deterred by the palpable lack of policing. Yet Westerners who do venture into this lively mercantile hub come to experience something of the real Baghdad. They come for the antique charms of its twisting streets and dusty alleyways, many of them so narrow you can practically span them with outstretched arms; for the smells of masgoof, the local fish speciality, smoking in open doorways; the sweaty clangour of artisans at work beating metal and scraping leather; and to rub shoulders with upright Bedouin chiefs dressed in impeccably starched dishdashas going about their everyday business.

Often they are hunting for hidden treasures. They know that there are medieval churches in the Old City, built by Armenian and Nestorian Christians, and elaborately carved twelfth-century gates tucked away in neglected corners, between the noisy souks and bustling coffeehouses. There are also imposing stone buildings dating, mainly, from Ottoman times. Occasionally, a dark street opens up onto the banks of the River Tigris, where an unexpected burst of sunlight flashes up off the water. But mostly the narrow streets fold in on themselves, hugging their secrets.

At midday, when the sun is blisteringly hot, these streets are thronged with people, dodging the wooden carts of goods pushed by small, barefoot boys and the donkeys laden with burlap bags, and lifting their robes to avoid being splattered by the filthy water that trickles down the middle of the street. The Western visitors mingle in, revelling in the places very survival, for while the rest of Baghdad seems to have been have been sucked into the prevailing chaos, in the Old City the rhythm of life carries on just as it has always done, undisturbed either by the occupation or the fierce resistance to it.

I, too, had come to the Old City in search of the past, my familys past, coloured by fond memory and the lasting echoes of overlapping personal histories that I had come to know well over the years. And yet the enduring mystery was this: why were my relatives still so eager to relive it all?

The date was March 2004, ten months after President George W. Bush announced the end of major combat operations in Iraq. Despite the presidential assurances, war was still raging across the country, as the Americans continued to root out Baathist sympathisers, largely comprised of the most hardened core of Saddam Husseins supporters whod lost their influence with his removal. For their part, the Baathists, along with other less readily identifiable resistance forces, continued to fight back, and with brutal consequences. Baghdad was extremely dangerous. Especially for Westerners whose value as collateral or PR was just beginning to be recognised: Nick Berg, the Jewish-American contractor whose videotaped beheading shocked the world, was executed only weeks after I left. His death, in retrospect, marked the end of one kind of war and the beginning of another, more intractable kind.

Next page