This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 2004 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

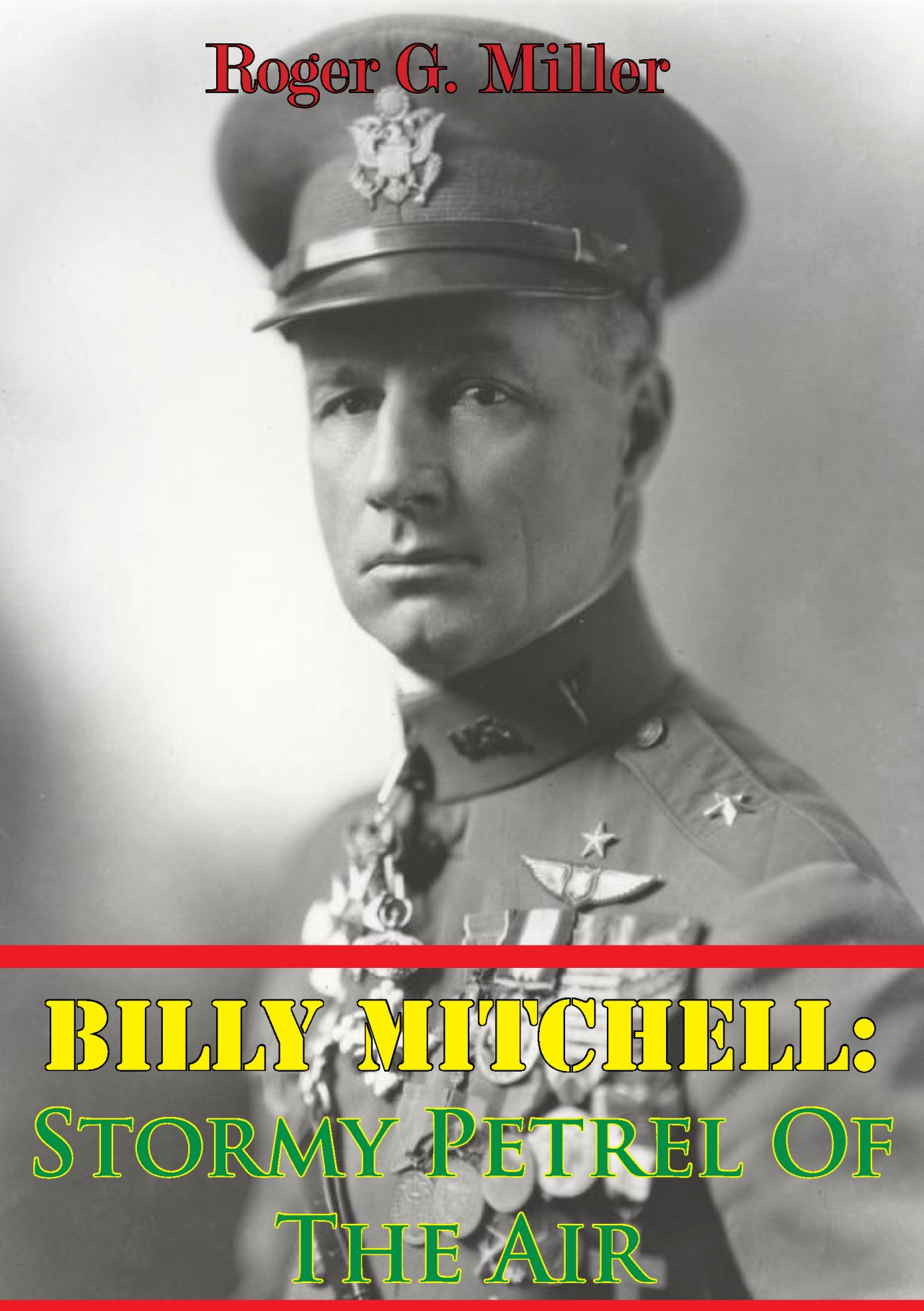

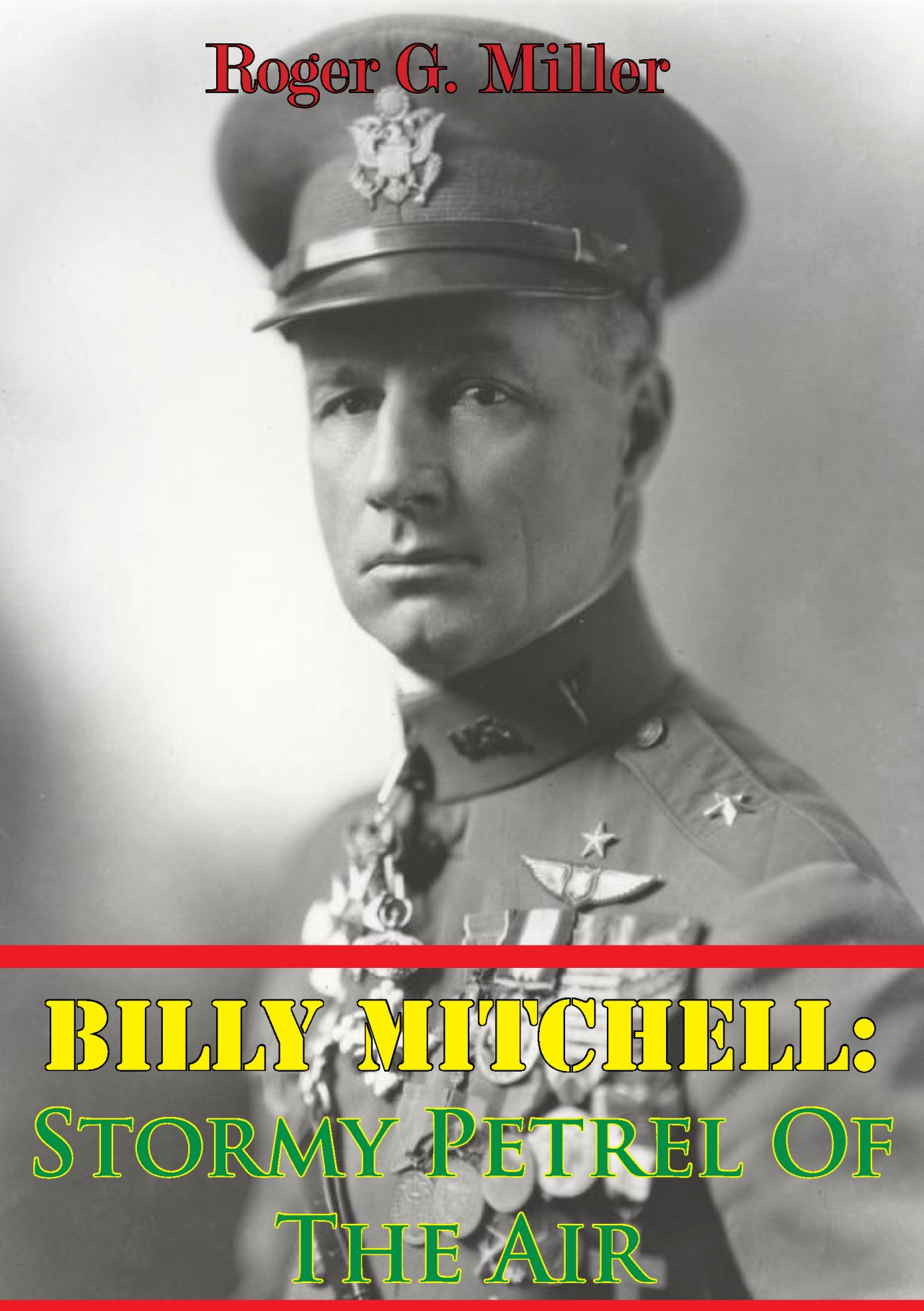

BILLY MITCHELL STORMY PETREL OF THE AIR

Roger G. Miller

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell personally led the attack on the Ostfriesland from his pennant-marked De Havilland DH4. (Courtesy U.S. Air Force Museum)

The Ostfriesland sinking, July 21, 1921. Escaping air from the hull seemed to some observers to be the sighs of a great beast dying.

BILLY MITCHELL STORMY PETREL OF THE AIR

petrel \pe- trel, p-\ [alternate of earlier pitteral ] : any of numerous seabirds; esp . : one of the smaller long-wing birds that fly far from land compare STORM PETREL.

Websters New Collegiate Dictionary .

He was known as the Stormy Petrel of the Airpetrel, a bird in flight. He was that, and he soared with eagles...

James J. Cooke, Billy Mitchell , p. 287.

On July 21, 1921, Brig. Gen. William Billy Mitchell circled high above the rough surface of the Chesapeake Bay, exultant witness to an event he had orchestrated and produced. Shortly after noon, the mortally wounded, former-German battleship Ostfriesland began to roll, turning completely over while air escaping from the huge hull gave sounds that some present interpreted as the sighs of a great beast dying. By one oclock it was over, and Ostfriesland had slipped below the surface. It was not the sinking that was unique, however. Modern battleships had sunk before. They had been lost in storms and split their hulls on reefs and rocks. They had been hit by torpedoes, crushed by shell fire, and even sunk by mines and scuttling charges. But no battleship had ever gone to the bottom as the direct result of aerial bombs dropped from the fragile airplane, a new invention then barely eighteen years old. Disbelieving observers aboard the nearby U.S.S. Henderson were shocked, appalled, and dismayed as the Ostfriesland disappeared. Among the naval officers were some with tears in their eyes. But for the outspoken, flamboyant Billy Mitchell it was fulfillment and vindication. He had prophesied that aircraft could sink battleships; had fought for the trials that had just taken place; and had selected, organized, and trained the airmen who had accomplished their mission. Sinking the Ostfriesland was in many ways the summit of his military career, and Billy was not about to let anyone ignore his victory. Command pennant streaming from his aircraft, Mitchell paraded past the Henderson waving his wings, rubbing salt into a deep Navy wound.

* * *

William Mitchellhe had no middle namewas born on December 29, 1879, into a wealthy and prominent Wisconsin family living at the time in Nice, France. Prior to the Civil War, his grandfather, Alexander Mitchell, had established the Marine Fire and Insurance Companya bank despite its nameand expanded it into a respected Milwaukee business. And during the war, he built and operated the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad. Alexander Mitchells business acumen had made him and his family wealthy by the time the war ended. His son, John Ledlum Mitchell, however, proved more interested in literature, languages, and travel, and would ultimately lose much of the family fortune. John enlisted in the 24th Wisconsin infantry during the Civil War and saw combat during several of the western campaigns. Following the war he traveled extensively, played a significant role in the Grand Army of the Republic, an organization of Union veterans, and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and later the Senate.

Billy grew up in Milwaukee, but his parents, especially his father, were often absent. Billy liked the outdoors. He hunted and fished and, especially, loved horses and horsemanship, an affection he would never lose. He was popular and charming, and as a youngster assimilated many of the characteristics that had made his grandfather successful, including self-confidence, drive, ambition, courage, competitiveness, and a certain ruthlessness common to nineteenth-century captains of industry. Though intelligent, Billy was not particularly studious. He received private tutoring at home and spent several years at Racine College of Wisconsin, an Episcopalian preparatory school. Tired of the strict discipline at Racine, however, he transferred in 1895 to Columbian Preparatory, later George Washington University, in Washington, D.C., where his parents resided while his father was in the Senate.

In April 1898, the United States declared war on Spain. Adventure called and eighteen-year- old Mitchell promptly abandoned his studies and enlisted as a private in the 1st Wisconsin infantry. It took Senator Mitchell a few days to catch up with his son, but within three weeks his influence was felt and the Army commissioned Mitchell as a second lieutenant in a volunteer signal company. Such influence would prove important to Billy, who actively cultivated individuals like Senator William Jennings Bryan, then serving with the volunteers, and Maj. Gen. Adolphus Greely, the Chief Signal Officer. Mitchell demonstrated considerable flair for soldiering from the first. He displayed energy and initiative and enjoyed the opportunity to lead small units. He suffered discomfort and hardship without complaint, and his skill with horses and guns impressed professional soldiers. Unfortunately for Billy, however, Spain sued for peace before his unit could get out of Florida. Mitchell then used his fathers leverage to join the occupation force in Cuba, which he reached in December 1898. He spent much of the next few months stringing miles of telegraph wire throughout Santiago Province. Mitchell liked the work, enjoyed the life, and began consider the military as a career. As an accomplished horseman, he preferred the cavalry, but the Signal Corps offered him the higher rank of first lieutenant. Despite opposition from his parentsas members of the upper class, they regarded the military as beneath their sonMitchell accepted the Signal Corps offer.

It proved a wise choice by Mitchell and a good one for by the U.S. Army; Mitchell proved himself an excellent officer. His first assignment, to the Philippines in October 1899, coincided with the beginning of a two-year campaign against Emilio Aguinaldo. Mitchell earned considerable distinction and warm praise during the campaign, reinforcing his personal belief that he could succeed in the military. On the other hand, recognition that his element was service in the field with troops, not stagnation in a peacetime garrison, made him cautious about committing to a career. Billys next assignments made all the difference. In the summer of 1901, General Greeley ordered him to Alaska to survey routes for a communications system across the territory. Mitchell spent two years leading small teams that erected over 500 miles of telegraph lines. The work in heavy snow and arctic conditions was brutal, but Mitchell thrived. This experience with individual responsibility and his unqualified success was critical. First, he gained tremendous confidence in his ability to accomplish major projects, a confidence reinforced by his belief in the natural superiority of his class. Second, and perhaps more important, instead of regimental duty under close supervision and the necessity of working in harness with other officers of equal rankthe rough-and-tumble school of the soldierMitchells experience was largely that of an independent commander operating on his own with little supervision.

Next page

![Roger G. Miller - Like A Thunderbolt: The Lafayette Escadrille And The Advent Of American Pursuit In World War I [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/book/291189/thumbs/roger-g-miller-like-a-thunderbolt-the-lafayette.jpg)