RIVERHEAD BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2022 by Jennifer Quilter

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint lines from A Wave by John Ashbery. Copyright 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984 by John Ashbery. Reprinted by permission of Georges Borchardt, Inc., on behalf of the author. All rights reserved.

Riverhead and the R colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Quilter, Jenni, 1980- author.

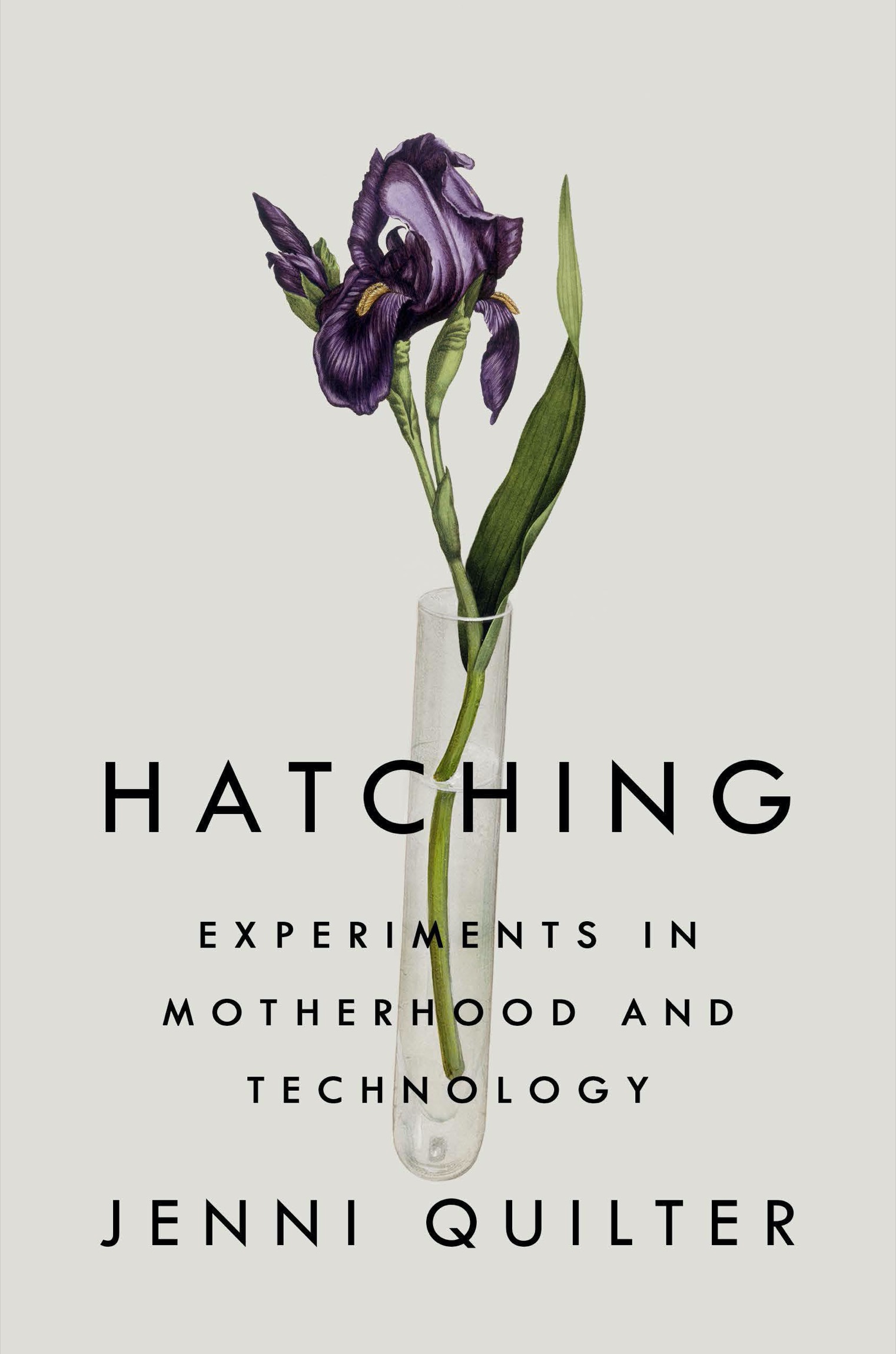

Title: Hatching : experiments in motherhood and technology / Jenni Quilter.

Description: New York : Riverhead Books, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022001714 (print) | LCCN 2022001715 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735213203 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780735213227 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Quilter, Jenni, 1980- | InfertilityPatientsUnited StatesBiography | Women college teachersUnited StatesBiography | Fertilization in vitro, Human | Pregnancy | Reproductive technologyHistory

Classification: LCC RG135 .Q855 2022 (print) | LCC RG135 (ebook) | DDC 362.1981/780092 [B]--dc23/eng/20221013

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022001714

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022001715

Cover design: Grace Han

Cover images: (flower) Photo Leonard de Selva / Bridgeman Images; (leaf) Photo Bridgeman Images; (test tube) Trish OHare / Bridgeman Images

Book design by Lucia Bernard, adapted for ebook by Maggie Hunt

pid_prh_6.0_141971234_c0_r0

For Stephanie

Contents

1

GRAFT

Occasionally there are books that you encounter like arrows: they arrive with velocity and a distinct whump. Naomi Mitchisons Memoirs of a Spacewoman was like that for me. It was published in 1962, and I picked it up around 2017. Its not widely known. The book collects the expedition notes of a spacewoman called Mary and her visits to various planets, and it is the ventriloquized voice of the future, a way for Mitchison to imagine the fantasies and freedoms she thought the future might afford a woman like her.

Its not that Mitchison hadnt already carved out for herself an extraordinarily rich and varied life. By the time Memoirs came out, she was sixty-five years old and living in Scotland. She had given birth to seven children, traveled extensively, and openly talked about her open marriage (her only regret, she said on her ninetieth birthday, were all the men with whom she didnt sleep). Then there were the political appointments, and numerous societies, commissions, and councils, many of them revolving around socialism, birth control, and Scottish economic development. She wrote, by her own account, compulsively, and though Memoirs of a Spacewoman was her first science-fiction novel, she had already published dozens of books by then: mostly novels, but also travel writing and autobiography. She would go on to write more than ninety books by her death, in 1999, at 101.

Mitchison was very matter-of-fact about all this in her memoirs, and Mary, the narrator, is similarly prosaic: in the novel, the extraordinary isnt ordinary, but it shouldnt be considered any kind of rare or bizarre exception; for all we know, there could be hundreds of Marys in space, and we just happen to be reading about this one.

Mary has six children. Four of the children are human, and two are alien. One child, Ariel, is a tentacle-like creature with whom Mary communicates through number theory (the tentacle can tap out number sequences on her leg). Another, Viola, is described as half-human, half-Martian. Mary conceives a few of these children back on Earth, and a few in space. Some, but not all, have biological fathers. Mary does not raise all of them together. In this new world, her age has nothing to do with her reproductive clock. Because time moves more slowly away from Earth, and because she embarks on a number of space missions to different worlds and solar systems, each time Mary returns to Earth she returns to a different world: there is no one who ages contiguously with her, no lover, no family, not even her own children, who are infants when she embarks on one trip, then teenagers when she returnsand she has only aged a year. The work of child-rearing, all the dinners and washing and endless negotiations, can be excised in one hyperspace leap. Mary mentions feeling guilty only once.

For anyone who has felt the queasiness of pregnancy, the sudden conviction that your body is not your own, the inner roiling and the splitting open, the endless days and nights of cleaning and feeding, Mitchisons freedoms are fascinating. For anyone who has not fallen pregnant or raised a child, but who has been caught between the fearing and the yearning, Mitchisons recasting of the obligations of parenthood is also irresistible. Mary has a biologists eye in her attention to cause and effect, and is obviously interested in how our physiological structure directs our cognitive and moral frameworks. Her tone is professional, even impassive: she sees no disconnect between scientific exploration and reproduction, and is not surprised that her expeditions involve physiological experiments of more than one kind. Her pregnancies defamiliarize two discoursesone of scientific knowledge, the other of motherhoodat the same time. Her acts of conceiving are not something you balance with work: it is the work. This conceptual reorganization is akin to a shift from ptolemaic to heliocentric conceptions of the universe. The baby is no longer the thing around which everything revolves. Rather, its the womans body, and her decision to experiment with it. How one feelscramps, blood, cell growth and death, hormone swingsis a site of analysis rather than a vaguely taboo topic.

The first time I read Memoirs of a Spacewoman, I felt relief so strongly that it registered as a kind of digestive ache. Here was a woman who had thought about birth in terms I instinctively understood but rarely recognized in the world around me.

Mitchison grew up in Oxford, England, the daughter of a scientist, and was educated at the well-regarded Dragon School, the only girl in a classroom of boys. She was regularly allowed into her fathers laboratory. With her brother, J. B. S. Haldane, she carried out a number of experiments exploring Mendelian inheritance patterns in guinea pigs. These were all good augurs for her intellectual independence, but when she turned fourteen, her parents decided to homeschool her rather than send her away to boarding school as they did with her brother. Although she later studied at the University of Oxford, she was a day student, enrolled in a womens college that had a different course of instruction than her brothers college, barely a mile away. Mitchison knew what she was missing out on because her brother allowed her to pal around with his friends in his college rooms. It was Haldane, not Mitchison, who published their early genetic experiments with guinea pigs, and it was her brother who, in 1924, published a small pamphlet titled