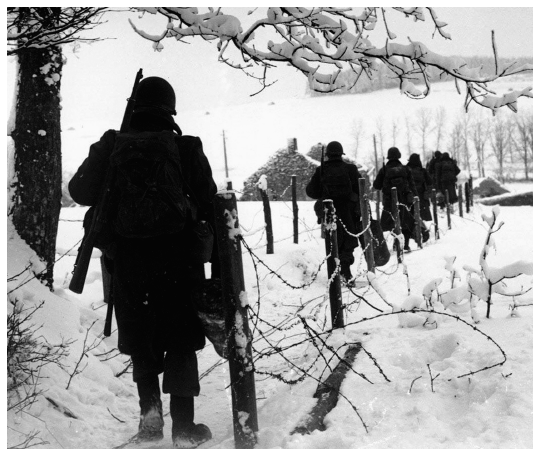

Facing title page: 3rd Infantry Division soldiers moving toward a Belgian village in January 1945 following the relief of Bastogne. (National Archives)

2019 Thomas S. Helling

Maps by Paul Dangel 2019 Westholme Publishing

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Printed in the United States of America.

Talk not thou to me of flight, for I deem thou wilt not persuade me. Not in my blood is it to fight a skulking fight or to cower down; still is my strength steadfast.

Preface

HISTORY IS WRITTEN NOT MERELY TO DESCRIBE BUT TO UNDERSTAND. And at its most granular, history portrays the range of human emotions that produced actionsgood or badthat shaped destiny. In that sense it is a study of behaviorindividual and collectivemotivated by deep-seated beliefs, desires, and social conscience in response to stresses internal and external. Most palpably, history defines a nobleness or wretchedness that brings forth the finest and vilest of mortal character. Endurance, perseverance, and survival are qualities repeatedly summoned for those caught up in whirlwinds of time, particularly in times of great conflict. Some embrace, others reject. They are stories of momentsindefinable stretchesthat assembled in total call forth again and again the immortal words of Charles Dickens: the best of times... the worst of times.

And at the extreme are the life-and-death struggles of armed human conflict. Warfare propels individuals into these most uncertain periods. We who examine from the safety of history will never fully appreciate men and women trapped in the dread of doom. But the finite spans of hours, days, or weeks that they bore register far into their moral fiber as if the rest of a lifetime was merely preparation and recovery. It is this we seek to milk from the pages of history, noble or ignoble passages and not just uninspiring recitations of chronology.

This book seeks to remember these heroesand understand. They are stories with beginnings and ends, but, more importantly, they are stories of images and feelings and commemorations. Graphic impressions seared into minds know not time and space; dates and hours and minutessoon melt awayonly instances remain. Huddled under jungle canopies or bullet-ridden tents or in icy shacks, men and women, devoted to caring only for others, found themselves beyond the boundaries of human tolerance, sometimes staring helplessly to watch unrequited suffering. Many, long dead, will never see these pages. But their memories inspire and reassure that we humans are all connected. That extensions of ourselves have existed before. That we would hope our actions could match heroics of those who came before. That this world continues to be a better place because of them.

It is the specific focus of this work to examine an ordinariness about the human condition that becomes extraordinarynot just the idea of combat itself, although enough of a traumatic event in its own right, but the immediate peril of annihilation, whether from sudden explosion, a snipers bullet, or capture and subjugation. These are circumstances of entrapment and siege, settings where hope and mercy have evaporated, and all face the inevitability of destruction. War has produced sieges for centuries as an effective form of brutal capitulation. One can imagine the tribulations of men at arms: surrounded, hungry, desperate. But what of the noncombatants? What of the mercy workers whose intent is to save and not destroy? Let us exam them in their valor and equal desperation. Of all the tragedies history might furnish, let us focus on five: Bataan, Anzio, Bastogne, Chosin, and Khe Sanh. Each presented different challenges: climate, geography, tactics, and resources that assailed the resiliency of its defenders. The Bataan Peninsula, a singularly unattractive locale for defense, was hot, humid, and disease ridden. The deprivations of all vital material were soon lacking. Besiegement was complete. Capitulation virtually assured. Anzio was a military blunder salvaged only by superhuman efforts at resistance and resilience, and by a uniquely robust supply chain seaward that kept the beachhead lifelines open. At Bastogne, encirclement by a rabid, fanatical enemy spelled disaster, aggravated by extremes of cold and demoralizing absence of casualty care. The Chosin retreat, fought in frigid temperatures, might have ended in complete annihilationand basically did so for many of the combatantswere it not for the sturdy leadership and dogged tenacity of Marine infantry. French capitulation at Dien Bien Phu a dozen years earlier loomed large for the Khe Sanh garrison, as Vietnamese regulars crept dangerously close to their perimeter, and their tenuous lifeline was a hazardous airborne journey into bullet-filled airspace. In those horrid places, American boys and girls bled real blood, endured endless bombardments,fought ravaging disease, followed familiar frigid footpaths, and vied for dwindling rations. In those tents and trenches and dugoutsbe they doughboy or jarhead, medic or corpsman, doctor or nursethey would wonder like the besieged from the times of Troy what minute what hour what day would be their last. What manner of brutality would usher in their demise? What ghastly miscalculation brought them this destiny? Could we rise to superhuman intensities as they had? Could we still exude compassion and caring and patience for those in extremis as they did? Immersed in their personal agony, could we be as noble as they?

FROM THE SECOND WORLD WAR ON, American combat casualty care involved early surgical intervention for those with life-threatening injuriesas close to the battlefield as prudent. Nontransportables they were calledmen so unstable that any attempt to evacuate would likely prove fatal. Drs. Edward Churchill and Michael DeBakey, army surgery consultants, devised teams with seasoned surgeons to link with field hospitals as mobile units following troops. By the Korean conflict they were called mobile Army surgical hospitals. A minority of wounded needed their services. Most wounds were mercifully not life threatening, even though urgent care was desirable. For those, delays could be toleratedto an extent. But inability to extract any woundedparticularly seriously woundedaffected all casualties sooner or later. Failure to stop hemorrhage, improper or negligent cleansing (debridement), and source control of sepsis took a toll, often leading to crippling complications and even mortality. This was the conundrum of siege: the dual needs for early surgical intervention and prompt evacuation. Logistics held the key. Supply and extraction ultimately meant the difference between life and death, between resistance and capitulation.

Heavy combat consumed medical material: blood, bandages, plasma, morphine. Resupply became a practical and psychological issue. Doctors and nurses needed fresh stocks, and the battle wounded needed hope. That wounds could be inspected, cleaned, and dressed in a timely fashion was paramount to surgeons and nurses, but also to patients. The illusion that doctors could resurrect the dying was key to maintaining a fighting spirit, key to necessary risk taking. Without it, when comrades were seen to suffer needlessly, when soldiers were surrounded by the dead, resolve weakened. For medical staff under fire, the focus on the wounded wastherapeutic, a welcome distraction from danger about which most could do little. Yet siege imposed limitations. Meatball surgerycarving away of devitalized tissuemight be sufficient for the majority of cases and might be possible under even the most austere of conditions, but complex repairs could be impossible. For these patients, the slow spiral to death was uniquely unsettlinga direct consequence of circumstances, not science or ability. And all became painfully aware of it.