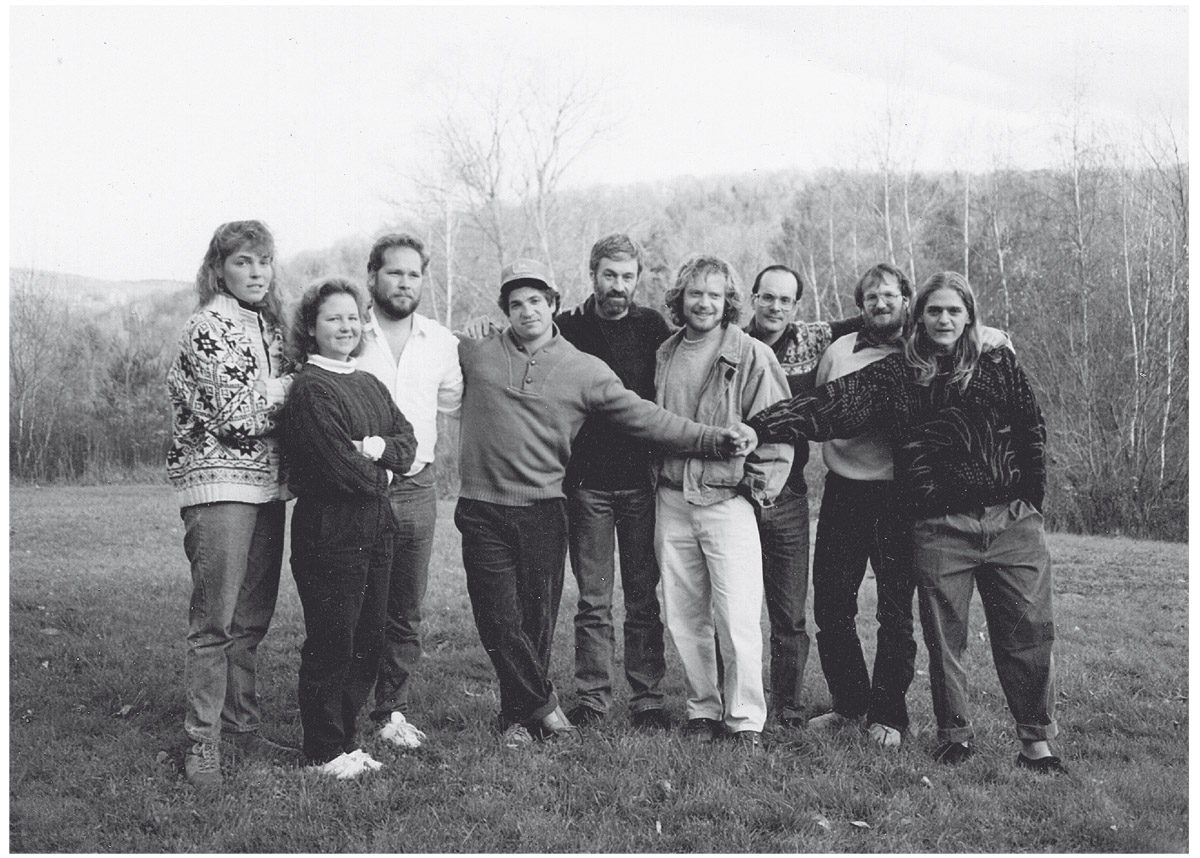

The crew of Anne Kristine. From left to right: Jen Irving, Barbara Treyz, Marty Hanks, Joey Gelband, Peter Abelman, John Nuciforo, Nelson Simon, Laingdon Schmitt, Damion Sailors. PHOTO BY MARY ANN BAKER

HURRICANE ALMA

Year: 1966

Category: 3

Highest Sustained Wind: 125 mph

M Y FIRST HURRICANE was the year I was seven.

My parents had been to Florida the year before with just my brother, Rob, to see relatives visiting from Bolivia, and they wanted to take me because Miami looked beautiful, as my mother put it. So, the four of usMami, Papi, Rob, and Ipacked our car and set off from our house in Adelphi, Maryland, made a quick loop halfway around the Beltway, and began the straight shot down I-95, 1,065 miles to Miami Beach.

It must have been a delicate time for our young family, trying, I suppose, to become more of a family. My parents had come to this country in 1961, bringing my grandfather to the DC area for treatment at Walter Reed, the military hospital. Papi, trying to establish his own medical residency, was essentially living at Prince Georges County Hospital, while my mother cared for her father in the tiny apartment the three of them shared. They had left my brother and me in La Paz with our grandmother, where we lived apart from them for almost a year.

One day our grandmother told us we were going to Wa-shing-ton, that sing-song place that had become a fairytale kingdom to me, the faraway land where my parents lived. Suddenly, we were on a plane, Rob and I crying the whole way, from La Paz to Miami then on to Washington National Airport. And then we were getting off in a place that was hot and muggy and strange, and nowhere did we see the aunties and uncles, cousins and nannies who populated the world we knew. That was over. I clung to my abuela as these two smiling, vaguely familiar people approached, their arms reaching for me. When you first saw me, you werent sure who I was, my mother would later say. Your abuela was the mother you knew.

I dont believe we planned to stay forever, but time passed, and we just never left. Soon the family pooled together enough money to buy the little house on Kirston Street that would be our home for the next several years. In 1966, still struggling financially but feeling more settled, Mami and Papi must have thought that our first family vacation would be just the thing. As Mami remembered it:

We just decided to drive to Miami Beach. We didnt know the names of hotels or prices of hotels. We didnt have that much money. I went into this hotel, I asked how much it would cost for us to stay. We were only going to be there a few days, and they gave me a price for a room with a kitchenette that would be sufficient for the four of us, and we could even make breakfast there if we wanted to.

The next day we came downstairs ready for a day at the beach only to find the staff boarding up the hotel windows. A hurricane was coming, they said, and we had to leave. I wasnt sure what a hurricane was, but this didnt seem the right time to ask. The beach was empty, and the police were directing a long line of cars away from the hotel. Our vacation, it seemed, was over. Papi decided we would drive straight home.

We started out. Looking out the back of the car I could see dark, swirly clouds in the distance, and everything around us had a strange, gray tint. The air had that quality it does just before a storm, the feeling that something is about to happen. I later learned this is because of the falling pressure that accompanies a hurricane. Inside the car everything felt... right. My father was at the wheel, my mother beside him. Rob and I knelt on the back seat looking back at where we had been, waiting.

When I remember this day, I picture my dear mother, a woman who has lived so much of her life with a heavy heart, for whom happiness has always seemed as far off as heat lightning in the distance. I see her in this moment, a young woman of twenty-six, not so far past her own childhood, alone with her two boys and her husband. Laughing, she seems to be enjoying our unexpected adventure. She is oblivious to the danger. I had never heard of a hurricane, Mami told me later, much less seen one. In Bolivia we lived in little towns, with a river or a pond, so we had nothing to compare it to. In my mind she is happy.

Soon the rain began. With every mile we drove, the rain got harder, the skies darker. My father drove slower and slower, until you could have trotted beside us. Rob and I were restless, so Mami entertained us the best way she knew howby telling us scary stories. Now, every raindrop brought a new monster, every lightning bolt revealed a new menace. Looking back, it does seem an odd way to calm young boys in a potentially dangerous situation, but it worked. Today I love a good fright, and even at that early age I was drawn to these stories, as if by picturing the bad things out there, beyond our windows, we could feel safer somehow.

Eventually, we realized we were the only car on the highway. And then, lightseerie flashing red and white lightsappeared behind us. My father pulled over to the shoulder, and the lights followed close behind. After a moment, a state trooper approached my fathers window, looking tired, exasperated, and incredulous all at once. You do realize theres a hurricane headed this way, right? he said. My father, in his halting English, explained that we did indeed realize this, and that we were trying to make it home to Maryland. Folks, you need to get off the road. Theres a motel six miles ahead. You need to go there and take shelter. Now. We crawled off, all of us feeling a little chastened, and for the first time I could sense something like fear from my parents.

We pulled into the motel and huddled together in our rooms one big bed, listening as the winds got louder and the whole place shook through the night. With each thunderclap I held my mother tighter. Eventually I fell asleep and dreamt that I was looking out the motel window. In my dream the hurricane looked a lot like the twister from The Wizard of Oz, which I had seen for the first time not long before.

The next morning the skies had calmed and cleared. We learned from the motel receptionist that the storm had made it impossible to go back to Maryland the way we had come, so at breakfast my parents pulled out a map and charted our course home.

We traveled on state highways and county roads, crisscrossing our way north through Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia. We stopped at gas stations, scenic overlooks, and, at my insistence, every little country cemetery we came upon. I loved cemeteries and found them oddly comforting. In the South they often consisted of small plots connected to a church or belonging to one family. The dates on the headstones were often over a hundred years old, and I was sure to check for families, to see how many generations were laid to rest together. Looking back, its difficult to fully understand this impulse, one that stayed with me into adulthood. Perhaps I wanted to imagine the lives of people who had been rooted in one place, families who had lived and died and buried their own in one location. I, who had lost my place, my people, and would live forever in a land that would never seem fully my own.