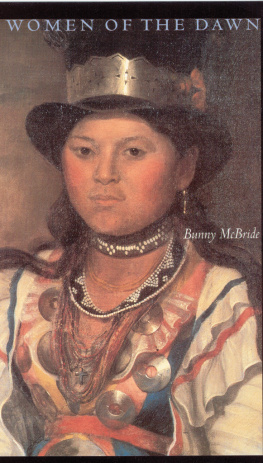

Rich in historic and visual detail, Women of the Dawn gives a poignant and compelling voice to long silent Native American women. The book evokes powerful and haunting emotions. Jill E. Shibles, president, National American Indian Court Judges Association

Penobscot women, like all Wabanaki women, have long been the guardians of their people. The four women profiled by McBride possessed energy and power that strengthened and sustained them. They changed the lives of those with whom they came in contact. A rare glimpse of these women can be seen within the pages of this book.-Donna M. Loring, Penobscot Nation tribal representative

I was enthralled by the passion and perseverance of the four Women of the Dawn whose courageous spirits ensured the survival of tribal lifestyles and values. Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve, author of Completing the Circle

An excellent portrayal of four Native American women. Hazel V. Jimerson Dean, Wolf Clan mother, Allegany Seneca Nation

1999 by Bunny McBride. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America

First Bison Books printing: 2001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McBride, Bunny. Women of the dawn /

Bunny McBride. p. em. Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8032-8277-3

1. Abenaki women -Biography. 2. Abenaki women History. 3. Abenaki women -Social life and customs. 4. New England -Biography.!. Title.

E 99. A 13 M 43 1999 305A88973-dc21 99-20617 CIP

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Dedicated to my American Indian women friends, who have taught me much about strength and resilience -especially

Dr. Eunice Bauman-Nelson

Dr. Hazel Jimerson John

sarah Lund

Jean Archambaud Moore

Elizabeth Phillips

Mary Sanipass

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My greatest debt of gratitude is to my husband, Harald Prins. Without him this book would never have made it to the finish line. I thank him for the sharing of ethnographic knowledge, for being a hawk on historical details, and for doggedly reminding me of my goal to write the stories of these remarkable women in a way that would embrace a wide audience. I also thank him for his steadfast enthusiasm and encouragement, evidenced in his willingness to critique numerous drafts of the manuscript, but most of all I thank him for his love and loyal friendship.

I wish to express my appreciation to the following people who read the manuscript at various stages and offered valuable input: Susan Els, my sister, fellow writer, and dear friend; Jean Archambaud Moore, Molly Delliss daughter and the most selfless informant I know; and Donna Loring, tribal representative to the Maine state legislature. I also wish to thank the scholars whose critical reviews of the manuscript fueled the writing of my final draft. Emerson Baker and an anonymous reviewer each drew attention to helpful references, Baker concerning Molly Mathilde and the other reviewer concerning Molly Ocketts childhood exile in Massachusetts. Colin Calloways comments prompted me to better address the needs of more traditional bread-and-butter historians by identifying for the readers the reconstructed scenes in the book.

Finally, I wish to acknowledge the many American Indian women and men who helped provide the foundation and purpose essential to the writing of this book. Through the years they have shared their knowledge, stories, and hospitality with me, and in numerous cases their friendship.

INTRODUCTION

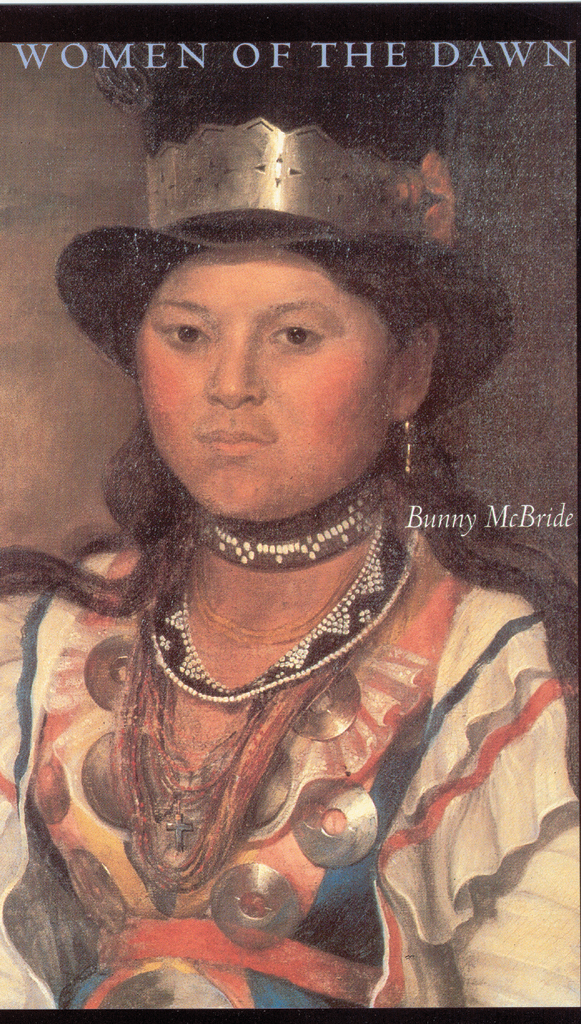

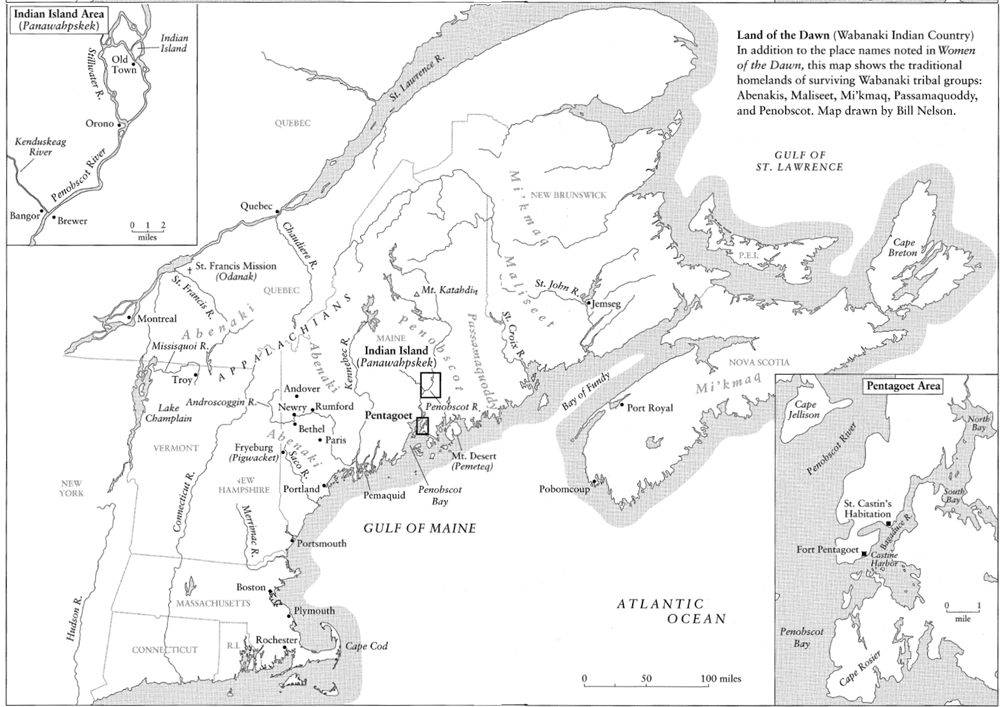

Women of the Dawn traces the lives of four Wabanaki Indian women. (Wabanaki means Dawnland, and it is the collective name given to Algonquian-speaking tribes living near the North Atlantic coast where the light of dawn first touches the American continent.) These women shared the same first name, Mary bestowed by Catholic missionaries, but distinctively pronounced by Wabanakis as Molly. Beyond a name, they shared a tragedy born of European contact. In the face of this tragedy, they all dared to bridge the gap between their own worlds and that of the European strangers who invaded their continent. Yet each woman possessed enough passion and perseverance to resist being swallowed up by the pervasive ways of the newcomers and to hold on to a vital core of herself and Wabanaki culture. As mothers, they bore seeds of continuity, rooted in the past, branching toward the future.

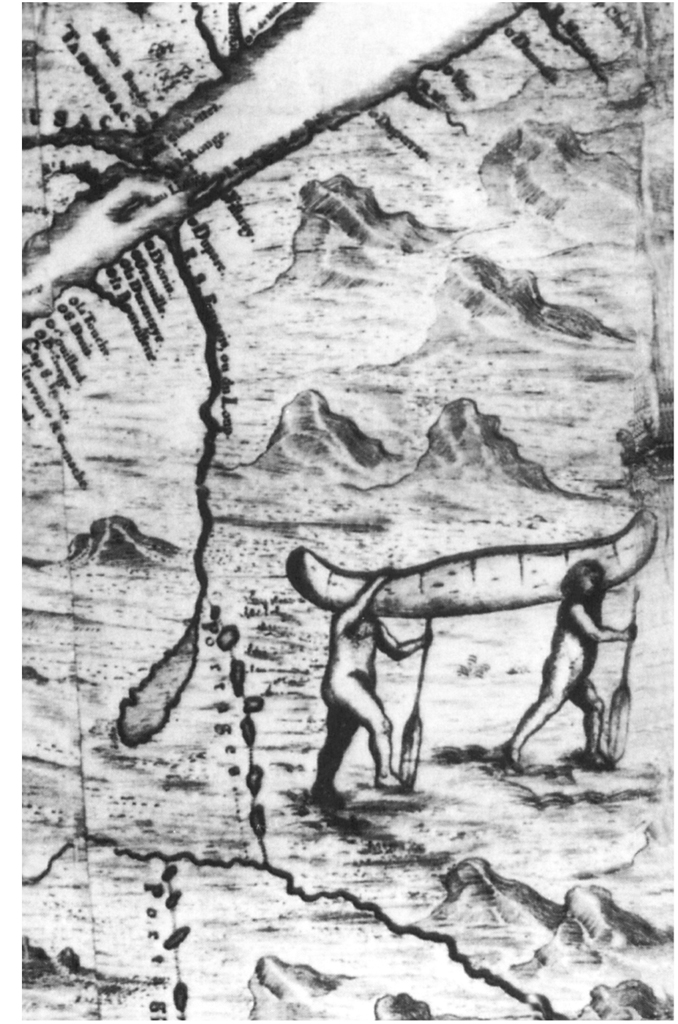

The book spans four centuries. It begins with Molly Mathilde, who was born on the eve of the Wabanakis disintegration, and ends with Molly Dellis, born at the dawn of their regeneration. Because Molly Dellis actually researched Molly Mathildes life, the stories form a circle, and Molly Dellis serves as narrator for each biography. Echoing the fact that all four women canoed the regions woodland rivers and moved from one stream to the next by way of foot-worn portage routes, the book carries readers from one profile to the next by way of brief portages. The portages are vignettes of Molly Dellis at critical passages in her personal life, moments when she contemplates the experiences of her female forebears in search of insight. Gazing into the distant mirror of their lives, Molly Dellis comes to know these women and brings them forward into her own life. Holding them in thought, she faces herself and gathers strength to carryon. Their stories become her story.

Combined, these brief biographies tell the long saga of colonization in northeastern America from the rare vantage point of women. They wed fact with feeling, and each story is a step in a spiritual pilgrimage from innocence to shrewdness to bitterness to wisdom. The journey is represented metaphorically by linking each life to a particular season the bountiful ease of summer, the foreboding of fall, the destitution of winter, the promise of spring.

Beyond biography, history, and spiritual journey, Women of the Dawn is a challenge to stereotypical views of American Indian women; the individuals in this quartet are gloriously distinct from one another. At the same time, the shared aspects of their lives especially motherhood and their struggle against colonialism show the vital roles that Native women play in the cultural survival of tribes. Each woman, in her own way and in her unique time and circumstances faced the question, What of the past will be carried into the future? The answer to that question lies not in this book, but in the lives of all of us, Indian and non-Indian alike.

Readers interested in this books theoretical orientation, research methodology, and writing strategy may refer to the Methodology and References section at the end of the book.

. Todays surviving Wabanaki communities include the Abenakis, Maliseet, Mikmaq, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot.