Please visit our website, www.garethstevens.com.

For a free color catalog of all our high-quality books,

call toll-free 1-800-542-2595 or fax 1-877-542-2596.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Brereton, Catherine.

Title: Women scientists in physics and engineering / Catherine Brereton.

Description: New York : Gareth Stevens Publishing, 2018. | Series: Superwomen in STEM | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN ISBN 9781538214657 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781538214121 (library bound) | ISBN 9781538214664 (6 pack)

Subjects: LCSH: Women in engineering--Juvenile literature. | Women in science--Juvenile literature. | Women scientists--Juvenile literature. Classification: LCC TA157.5 B74 2018 | DDC 620.0082--dc23

Published in 2018 by

Gareth Stevens Publishing

111 East 14th Street, Suite 349

New York, NY 10003

Copyright 2018 Brown Bear Books Ltd

For Brown Bear Books Ltd:

Text and Editor: Nancy Dickmann

Designer and Illustrator: Supriya Sahai

Editorial Director: Lindsey Lowe

Childrens Publisher: Anne ODaly

Design Manager: Keith Davis

Picture Manager: Sophie Mortimer

Concept development: Square and Circus / Brown Bear Books Ltd

Picture Credits: Cover: Illustrations of women: Supriya Sahai. All icons Shutterstock. Alamy: Science History Images .

Character artwork Supriya Sahai

All other artwork Brown Bear Books Ltd

Brown Bear Books has made every attempt to contact the copyright holders.

If anyone has any information please contact licensing@brownbearbooks.co.uk

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright holder, except by a reviewer.

Manufactured in the United States of America

CPSIA compliance information: Batch #CW18GS. For further information contact Gareth Stevens, New York, New York at 1-800-542-2595.

Contents

The Study of Matter

Hertha Ayrton

Lise Meitner

Maria Goeppert Mayer

Lillian Gilbreth

Hedy Lamarr

The Ladies Bridge and Rosie the Riveter

Timeline

Gallery

Science Now

Glossary

Further Resources

Index

The Study of Matter

Physics is a curiosity about the world and a desire to understand what makes it tick. It is also a drive to invent: to create tools, machines, and feats of engineering.

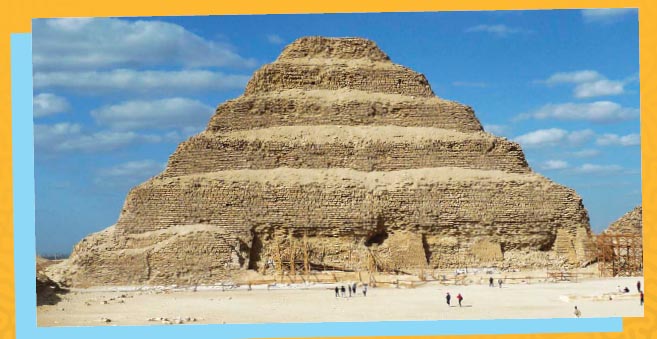

F rom ancient times, people have studied the universe and everything in it. This is physics the study of matter (the stuff everything is made of) energy, and the relationships between them. Also from the earliest times, people have put their minds to work as engineers, devising inventions to allow them to carry out tasks from ploughing fields, to bridging rivers, to firing weapons.

The first engineer we know of by name is Imhotep, engineer of this pyramid at Saqarra, Egypt.

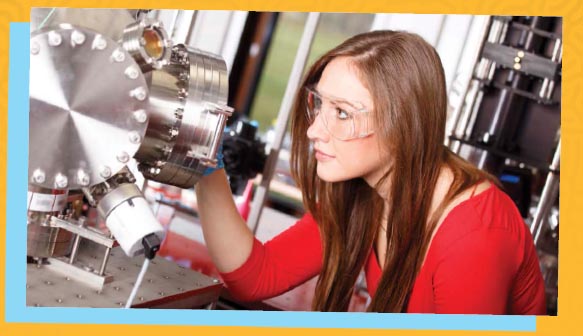

Physicists today continue the search to uncover the secrets of the universe.

MAKING SEnse OF MATtER

The ancient Greek thinker Aristotle was the first to use the term physics, writing about motion, gravity, and the planets. In the 1500s, Galileo Galilei made new discoveries about how the planets move. He is sometimes called the father of physics, although the title is also given to Isaac Newton, who came up with a theory of gravity, or Albert Einstein, whose theory of relativity is one of the greatest scientific achievements.

EXAMINinG ATOMS

From the late 1700s, scientists made advances in the study of atoms the tiny particles that are the basic units of matter and women have played a vital role. Lise Meitner and Maria Goeppert Mayer made discoveries crucial to the understanding of atoms. Much of physics today is about unlocking the secrets of how atoms behave. And just as exciting as scientific theory are the practical applications of physics electrical engineering, construction, communications, and inventions for the home. Despite facing huge obstacles, women have had a crucial part in the development of the study of physics and engineering.

Hertha Ayrton

British physicist Hertha Ayrton invented a new kind of electric streetlight and blazed a trail for women electrical engineers and inventors.

British physicist Hertha Ayrton invented a new kind of electric streetlight and blazed a trail for women electrical engineers and inventors.

H ertha Ayrton was born Phoebe Sarah Marks on April 28, 1854, near Portsmouth in southern England. She was one of eight children her father was a Polish Jewish immigrant watchmaker and her mother was a seamstress. The family struggled to make a living, but Hertha was lucky enough to get an education. At age nine she moved to London to become a pupil at her aunts school. She had lessons in French and music, and learned math and Latin from her cousins. At age 16, she started work as a governess.

Errors are notoriously hard to kill, but an error that ascribes to a man what was actually the work of a woman has more lives than a cat.

MATH MENTOR

While working as a governess, Hertha met Barbara Bodichon, a wealthy woman who supported womens education. Madame Bodichon was impressed with Herthas ability at math, so she paid for her to have advanced math lessons, and later for her to go to Girton College, Cambridge. This was the first womens university in England, cofounded by Madame Boudichon herself.

SPARKs OF SCIENCe

Hertha was studying math, but soon found the sparks of the interest that would drive her science and invention. She devised a line divider that could be used to mark out a line into any number of equal parts. This was useful for engineers and architects. The invention received a lot of press attention.

Hertha had to struggle to get her work recognized. She was friends with Marie Curie, also a star woman physicist with Polish roots.

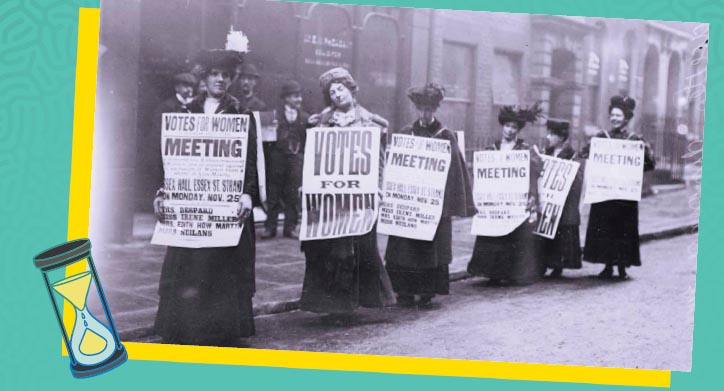

Hertha supported Madame Bodichons work for the suffragette movement, which campaigned for women to get the right to vote.

In 1884, Hertha began attending a technical college in London, to learn about electricity. The teacher was Professor William Ayrton, a pioneer of electrical engineering and a Fellow of the Royal Society. William became Herthas husband and inventing partner.

A QUIEt, BRIGHT LIGHT

In the 1890s, electric streetlights made a hissing sound. Hertha and William wanted to improve the technology, but it was Hertha who made the breakthrough. One day she was going through Williams research papers and trying to repeat some of his experiments when she made an important discovery. She realized that the hissing noise was from a type of chemical reaction called oxidation. This discovery meant that she was able to invent a new arc that made a quiet, bright light.