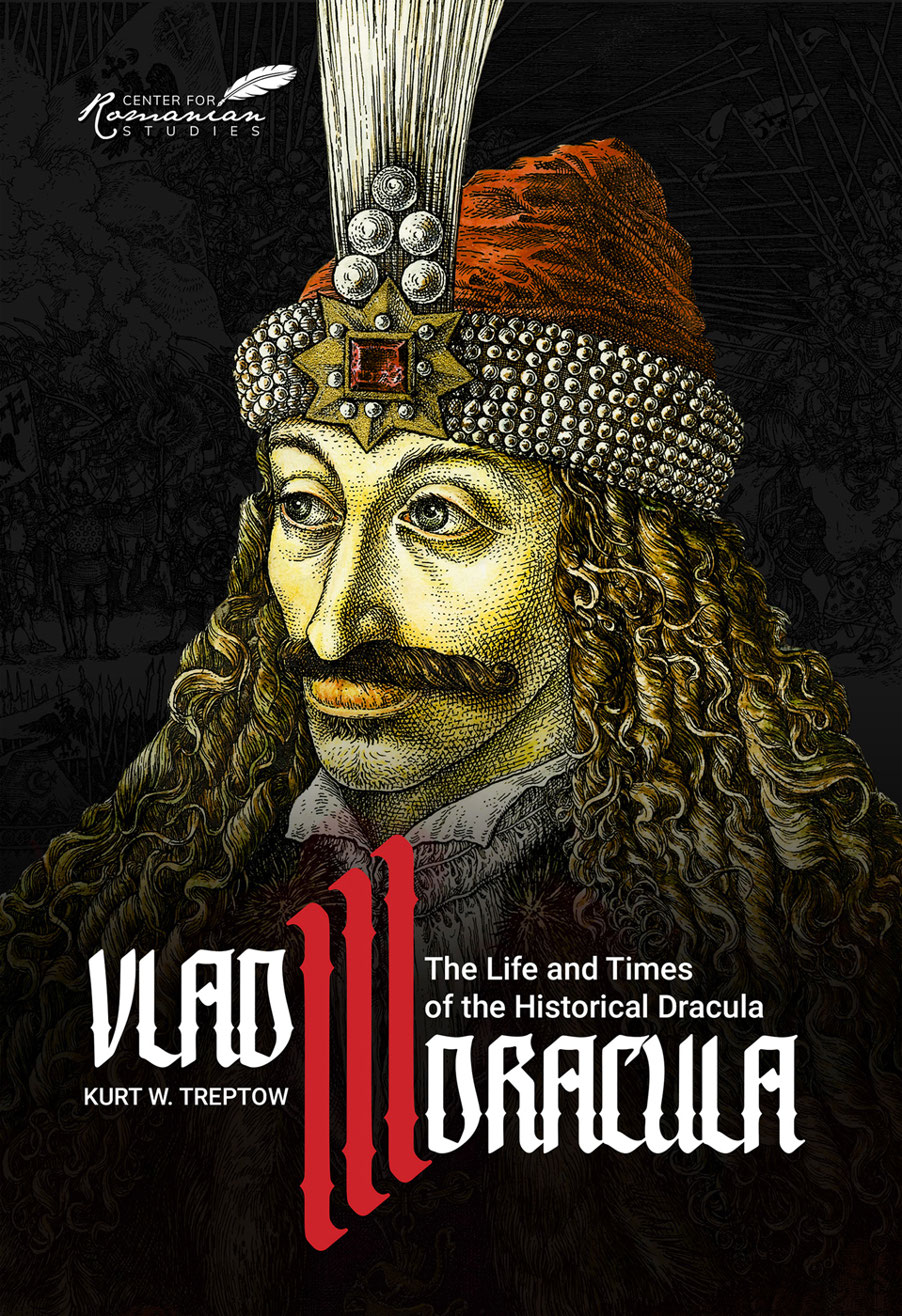

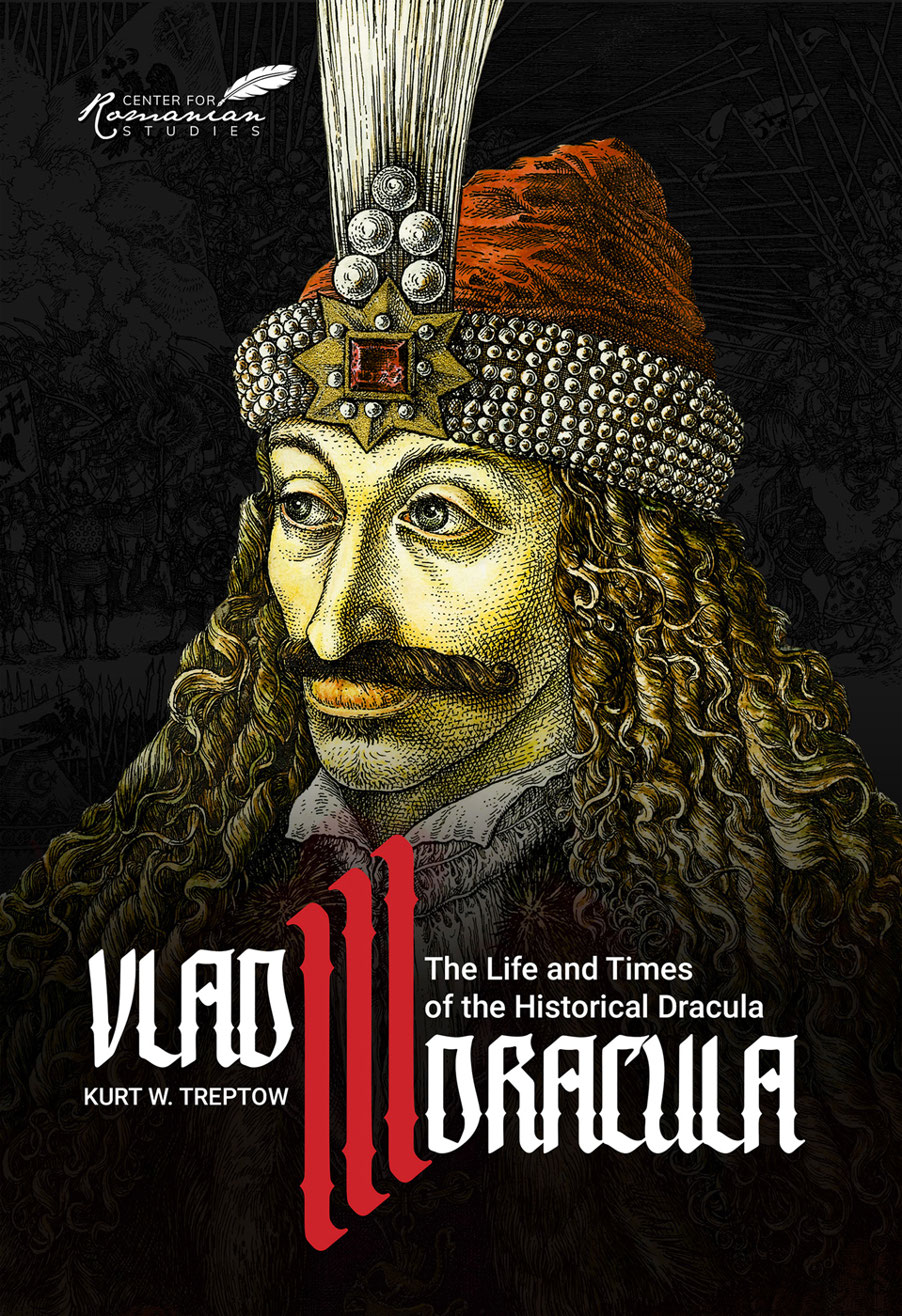

Vlad III Dracula

The Life and Times of the Historical Dracula

Kurt W. Treptow

Vlad III Dracula

The Life and Times of the Historical Dracula

With Original Illustrations by Octavian Ion Penda

The Center for Romanian Studies

Las Vegas Chicago Palm Beach

Published in the United States of America by

Histria Books, a division of Histria LLC

7181 N. Hualapai Way, Ste. 130-86

Las Vegas, NV 89166 USA

HistriaBooks.com

The Center for Romanian Studies is an independent academic and cultural institute with the mission to promote knowledge of the history, literature, and culture of Romania in the world. The publishing program of the Center is affiliated with Histria Books. Contributions from scholars from around the world are welcome. To support the work of the Center for Romanian Studies, contact us at info@centerforromanianstudies.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or repro-duced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photo-copying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020930220

ISBN 978-1-59211-028-5 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-59211-038-4 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-59211-214-2 (eBook)

Copyright 2022 by Histria Books

Contents

Preface

The earth is a nursery in which men and women play at being heroes and heroines, saints and sinners; but they are dragged down from their fools paradise by their bodies: hunger and cold and thirst, age and decay and disease, death above all, make them slaves of reality.

George Bernard Shaw, Man and Superman

The Middle Ages produced many legends and heroes that remain today very much a part of our contemporary culture; one need only refer to the tales of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, or of the outlaw Robin Hood, both familiar subjects of literary works and films, as examples. Amidst the struggle to halt the Ottoman onslaught in southeastern Europe, the historical figure of Vlad Dracula emerged to become a legend in his own time, and he has remained such throughout the centuries. At different times and in different places, he has been portrayed as either a saint or a sinner and, in one sense or another, continues to be viewed in this manner.

Vlad III Dracula, who at three different times (1448, 1456-1462, and again in 1476) occupied the throne of the small Romanian principality of Wallachia to the north of the Danube, opposed Turkish efforts to dominate his land, launching an offensive against Ottoman strongholds along the Danube during the winter of 1461-1462 and trying to withstand the massive invasion of Wallachia led by Mehmed the Conqueror during the following summer. Despite this, many sources portray Vlad as a man of demonic cruelty, the embodiment of all that is evil. For example, the German Stories tell how:

he invented frightening, terrible, unheard of tortures. He ordered that women be impaled together with their suckling babies on the same stake. The babies fought for their lives until they finally died. Then he had the womens breasts cut off and put the babies inside head first; thus, he had them impaled together.

Instead of a hero who defended Christendom against the Islamic onslaught, these stories speak of a man who, on St. Bartholomews Day, ordered that two churches be burned down and plundered of their riches and holy vessels. Likewise, the Slavic Stories about Dracula speak of a devil, so evil, as was his name so was his life.

The controversy surrounding the origin of his very name Dracula underlines the problem of the two contradictory images of the man. Vlad was called Dracula and signed his name as such in documents issued from his chancellery because he inherited the name from his father, who Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg had made a member of the Order of the Dragon, a crusading order founded to halt the advance of Islam into Europe. While in modern Romanian the name Dracula means devil, in the fifteenth century it also had the meaning of dragon. Dracula meant son of the Dragon, referring to his father Vlad II Dracul, while the etymological evolution of the word and the creation of the legend has transformed it to mean son of the devil, a name that has become synonymous with vampire in Western culture. While many Romanian scholars and others object to using the name Dracula because of its unfortunate evolution and prefer to refer to the prince as Vlad epe or the Impaler, I prefer to retain the name Dracula, the name which Vlad himself used and the name by which he, as well as the other sons of Vlad II, is referred to in fifteenth century chronicles. Despite its later evolution, Dracula was a prestigious name, part of the distinguished heritage of which Vlad took pride. The name Impaler, by contrast, stresses his cruelty and plays into the myth of the demonic tyrant from which the vampire stories evolved.

The contradictory images of Vlad III Dracula present a paradox. How could the same man at once be seen as a hero fighting for the cause of Christianity, while simultaneously being viewed as a villainous agent of the Devil? The answer, of course, must be sought in the specific political, social, and economic contexts within which Vlad lived and pursued his policies. By looking at the problem in this manner, it is possible to understand how these different images came into being and to have a better understanding of the historical Dracula.

As we shall see, one of the critical aspects of Vlads career, and the one which provides us with the richest documentation, is his conflict with the Turks. Vlad lived in the age when the Ottomans were establishing themselves in southeastern Europe, spreading the banner of Islam, and threatening to expand into Central Europe and Italy. The question of resistance to Ottoman expansion has usually been studied from two distinct viewpoints: either as part of a general effort by Christian states to stop the Ottoman advance into Europe or as an important moment in the national histories of the various peoples of southeastern Europe. Neither approach is adequate. In the former case, there is a tendency to underestimate the importance of the particular movement, and no effort is made to understand its internal dynamics and the specific social and economic factors behind it. Most often, the causes and motivations of these movements are merely ascribed to the desire to defend Christendom against the advance of Islam. On the other hand, in the latter instance, there is a tendency to overestimate the importance of the local movements, as well as to ascribe to them ideals that they did not possess, as defenders of a national idea, precursors of the nineteenth century national movements in their respective lands.

This book presents the life and times of Vlad III Dracula, prince of Wallachia. His motivations and goals will be analyzed, and I will investigate the reasons for his successes and failures. At the same time, I will study the context within which Vlad acted and investigate the situation of Wallachia in particular and southeastern Europe in general during the fifteenth century, as well as to present the structure of the Romanian principality at this critical moment in history. All of these elements limited Vlads course of action and influenced the decisions he made.

Next page