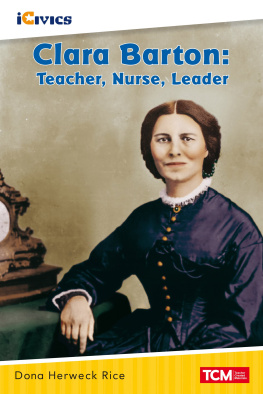

Facing title page: Clara Barton, c. 1865, photographed by Matthew Brady.

(Library of Congress)

2018 Donald C. Pfanz

Maps 2018 Hal Jespersen

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Produced in the United States of America.

My business is staunching blood, and feeding fainting menmy post, the open field, between bullet and hospital.

Preface

As a historian at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County Battlefields Memorial National Military Park, I first became interested in Clara Barton while reading Stephen Oatess A Woman of Valor, a book that describes her actions as a Civil War nurse. Oates portrays Barton as a heroine of mythical proportions, standing up to corrupt and incompetent officials, overcoming obstacles that would have defeated others, and saving countless lives by her resourcefulness and determination. At first, I accepted the stories he recounted at face value, but as their number multiplied I grew suspicious. There were too many coincidences, too much drama. Something wasnt quite right. Where did the author get his information? I began checking Oatess footnotes and to my astonishment discovered that the source for most of his heroic tales was Clara Barton herself. That set off alarm bells in my mind. Then and there, I decided to dig out the original sources, peel away the self-manufactured legend, and determine for myself what she really did during the war.

That was not as easy as it first appeared. As the parks staff historian, I had read thousands of letters and memoirs written by Union soldiers, and not one of them so much as mentioned Barton. I thought this odd given her heroic conduct and the fact that she was one of a very small number of women serving at the front. Surgeon J. Franklin Dyer was in charge of the Lacy House hospital inFredericksburg where Barton worked for more than two weeks in December 1862, yet his only comment about Barton came eight months later in a letter to his wife, and that reference was hardly flattering. General Marsena Patrick did not mention Barton at all. She encountered the Army of the Potomacs provost marshal in town on the day of the battle and gives a stirring account of their meeting. Yet in his diary Patrick is silent about the encounter. He obviously forgot about it or did not think it worth recording. Even more remarkable, Barton does not have a single reference in War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, the 128-volume set of official correspondence generated by the war, nor in the equally exhaustive Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Even the official history of the 21st Massachusetts, her pet regiment, mentions her just once and that in a very general sort of way. As one of just a few women working among thousands of men, Barton should have stood out. That she did not is remarkable and perhaps significant, for it suggests that her role on the battlefield may not have been as important as she later claimed.

Of the few accounts written by others about Clara Bartons experiences at Fredericksburg, most appear to be spurious. For instance, Miss H. P. Cleaves, in a speech delivered shortly after Bartons death, told the story of an episode that supposedly occurred near Fredericksburg in which a regiment of soldiers formed a line across a stream and knelt down on one knee forming a human bridge across which Barton walked. Cleaves insisted that Barton herself told her this story. While that may be true, it does not make it any less absurd.

Even Linus Brockett, in his otherwise admirable book Light and Shadows of the Great Rebellion, yielded to a measure of gullibility when he recorded that Union soldiers, in the midst of the battle, brought Barton a carpet for her quarters that they had stolen from a

Another source frequently quoted is an 1887 letter by Honora Connors, a woman seeking a government pension for her services as a Civil War nurse. Connors wrote to Barton on February 15, 1897, soliciting her assistance in obtaining the pension. In the letter, Connors recalled serving with Barton in 1864 at hospitals located in Fredericksburgs courthouse and Catholic church. I remember that you used to wear when you came in to visit the sick soldiers, a blue dress and a white cap; and that you used to sing Rally round the flag, boys! and that Gen. Barlows wife used to come down to the hospital sometimes with you. Unfortunately, Connors appears to have confused Barton with someone else. Barton was in Fredericksburg fewer than sixty hours in 1864, and thanks to her diary we know much about whom she met and what she did there. The diary says nothing about her meeting Arabella Barlow nor of her visiting either the courthouse or the Catholic church. While she might have made brief stops at those places, she could not have served alongside Connors for a significant period of time as the letter suggests.

Also open to question are some of the statements made about Bartons actions on other battlefields. A few are demonstrably false, such as surgeon James Dunns assertion that Barton visited his field hospitals at Cedar Mountain and Second Manassas or that she was still at Antietam when he left that place four days after the battle. Likewise without foundation is a statement that Barton supposedly made to Lenora B. Halsted that she helped administer chloroform in the operating room at the Poffenberger farm after all but one of the surgeons had fled. Other stories are merely improbable, such as that of a veteran who approached Barton after a postwar speech and

So how does a historian get at the truth when his subject is so firmly steeped in legend? The key is to revaluate the source material; in this case, primarily Bartons own writings. Were they written at the time or in later years? Was she writing for herself only or for an audience? When writing about her own deeds was she a reliable witness or prone to exaggeration? Can what she wrote be confirmed? If not, is it plausible? Such were the guideposts I used in pursuing my research for this book. The result, I hope, is a more realistic but no less remarkable account of Clara Bartons Civil War.

1

The Angel of the Battlefield

SINEWS OF STEEL AND NERVES OF IRON

Certain names in American history are recognized by virtually everyone: George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Abraham Lincoln, to name but a few. Clara Barton also falls into that category. Every schoolchild in America knows her nameor should. As a nurse, she was perhaps the most famous woman to emerge from the Civil War. But she did not stop there. Almost singlehandedly, she persuaded the United States Congress to ratify the Geneva Convention, an international treaty regulating the treatment of sick and wounded soldiers on the battlefield. At the same time, she founded the American Red Cross, an organization that to this day provides relief to victims of war and natural disaster. She is an American heroine and rightly so. But how much do we really know about her?