ALSO BY JEAN EDWARD SMITH

John Marshall: Definer of a Nation

George Bushs War

Lucius D. Clay: An American Life

The Conduct of American Foreign Policy Debated

(ed., with Herbert M. Levine)

The Constitution and American Foreign Policy

Civil Liberties and Civil Rights Debated

(ed., with Herbert M. Levine)

The Papers of General Lucius D. Clay (ed.)

Germany Beyond the Wall

Der Weg ins Dilemma

The Defense of Berlin

| SIMON & SCHUSTER

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

|

Copyright 2001 by Jean Edward Smith

All rights reserved,

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form.

SIMON & SCHUSTER PAPERBACKSand colophon are

registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Designed by Edith Fowler

Maps by Jeffery L. Ward

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Smith, Jean Edward.

Grant / Jean Edward Smith.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Grant, Ulysses S. (Ulysses Simpson), 18221885.

2. PresidentsUnited StatesBiography. 3. Generals

United StatesBiography. I. Title.

E672.S627 2001

973.8'2'092dc21 00-053794

[B]

ISBN-13: 978-0-684-84926-3

ISBN-10: 0-684-84926-7

ISBN-13: 978-0-684-84927-0 (Pbk)

ISBN-10: 0-684-84927-5 (Pbk)

eISBN-13: 978-0-74321-701-9

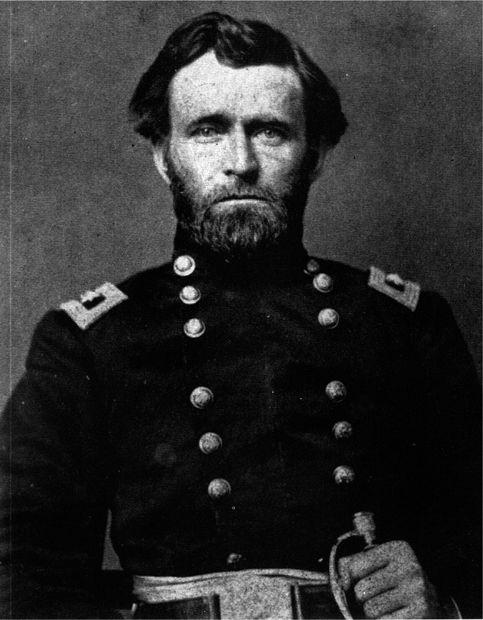

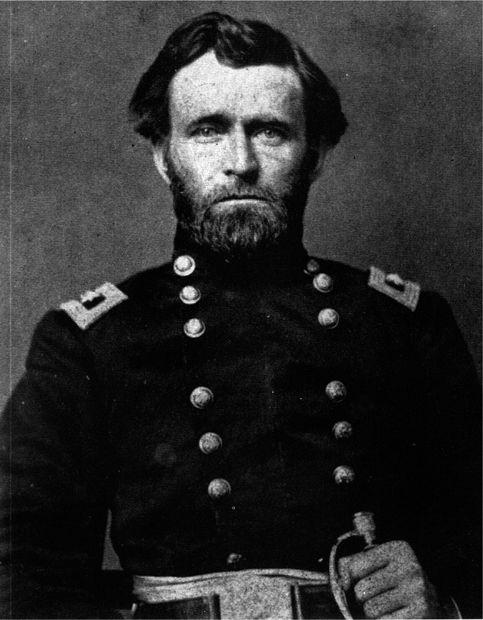

Frontispiece: Grant in 1863. Photograph by James Bishop, courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society.

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

Library of Congress: 1, 2, 59, 1114, 1621, 2329, 3133, 3537, 3947, 4952, 54

United States Military Academy: 3

Ulysses S. Grant Papers: 4

Galena-Jo Daviess County Museum: 10

National Archives: 15, 22, 30, 34, 38, 48

National Portrait Gallery: 53

To John and Elizabeth Drinko,

for their long and continued support

of American education

Contents

He was so pervaded by greatness that he seemed not to be conscious that he was great.

RICHMOND DISPATCH

July 26, 1885

Preface

WHEN I WAS TEN OR SO, my father took me and several of my cousins to Shiloh battlefield. We toured the site and as young Southern boys are wont to do, speculated enthusiastically how the Confederates could have won if only they had done this or that. My father, who was not an educated man, listened attentively and then in his soft Mississippi drawl cautioned us about what we were saying. It was bad for us to have lost, he admitted, but it would have been worse if we had won. The United States would not exist if the South had prevailed, and we should thank our lucky stars General Grant was in command that terrible Sunday in 1862. Grant never lost a battle, my father said, and he never ran from a fight. He held his surprised and battered army together at Shiloh, and when the smoke cleared it was the rebels who withdrew, leaving Mississippi open to the Unions advance. Grant saved the United States, my father said, and we should be damn glad he did. I had scarcely heard of General Grant before then, but from that day on I was hooked.

Ulysses S. Grant is one of the most complex figures in American history. He is an enigma, a paradox, and the challenge for a biographer is to reconcile the extraordinary disparities in his status and reputation. The story of his life combines abject failure and world fame. He demonstrated superb mastery of the worlds most powerful army, and was twice elected president with overwhelming majorities. Yet he was incompetent in personal financial matters, excessively generous toward old friends, and overly loyal to those who had served him. He was a withdrawn, seemingly inarticulate man whose writing sparkled with clarity. Lees army will be your objective point, he instructed Meade in the spring of 1864. Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also. No subordinate ever doubted what Grant intended, and no military action ever miscarried for lack of direction.

In the White House, he dominated the countrys political scene for eight years, providing the stability that steadied the nation after years of war and upheaval. Yet his presidency has been denounced by most historians, who rank it marginally above those of James Buchanan and Warren G. Harding. After leaving the White House, he failed miserably, suffering a humiliating bankruptcy when a corrupt business partner brought down the investment firm of Grant & Ward in 1884. Dying of cancer, he rose above the pain of approaching death to write the Memoirs, which achieved deserved fame as the greatest military autobiography in the English language. Back and forth, he careened from poverty to riches, from triumph to failure, from humiliation to glorification.

History, as a great historian has observed, is not a science, for every mind and every age regards it from a different angle. Modern historians followed along. Grant did not look like a president any more than he looked like a general. Seedy, careworn, always slightly rumpled and reeking of cigar smoke, he was easy to put down. Those who saw Grant for the first time during the Civil War often made the same mistake. But it was difficult to dismiss Donelson, Vicksburg, and Appomattox. Presidential accomplishment is more ambiguous, and there is always room to disagree about what constitutes political success.

David Herbert Donald, Pulitzer Prizewinning biographer of Lincoln, called Grant the most underrated American in history. Not because of his generalship, but because of his political skill as president. It is easy to see why Grant is often belittled, wrote Donald. He was not well educated, was not articulate in arguments, was not flashy, had no connection with the Eastern world of intellect and power. Yet he was the only president between Abraham Lincoln and Woodrow Wilson to be elected to two consecutive terms of office. His enemies ridiculed him and belittled him, but he survived them all.

It was not just Grants appearance, or his manner, or the fact that his enemies wrote better than his friends. Grant was condemned because of what he stood for. As president, he fought for black equality long after his countrymen had tired of the Negro question. He defended the rights of African-Americans in the South with the same tenacity that held the Union line at Shiloh. For Grant, Reconstruction meant a new order, with the freedmen integrated into the social and political fabric of the South. By the late 1870s that view was no longer fashionable. And for almost a hundred years, mainstream historians, unsympathetic to black equality, brutalized Grants presidency.

Similarly, biographies written by academic historians who stressed the inhumanity of war during the Vietnam era denigrated Grants role in saving the Union.

Grant made victory look easy. The clarity of his conception and the simplicity of his execution imparted a new dimension to military strategy. Grant ignored Southern cities, rail junctions, and other strategic points and concentrated on destroying the enemy army. His systematic deployment of overwhelming force not only led to victory in 1865, but established the strategic doctrine that became the basis for American triumphs in two world wars and more recently in the Persian Gulf. Grants personal contribution demands recognition. Sheridan maintained he was the steadfast center about and on which everything else turned.