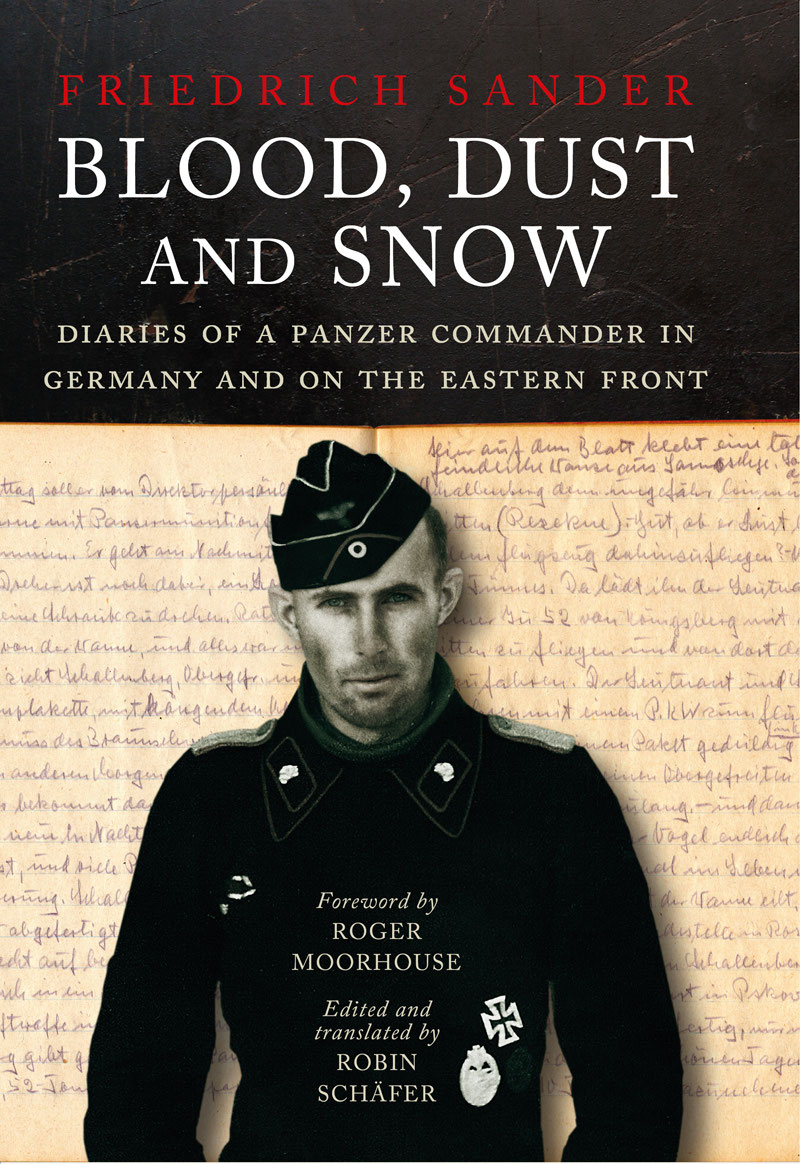

BLOOD, DUST

AND SNOW

Diaries of a Panzer Commander

in Germany and on the Eastern Front

19381943

FRIEDRICH SANDER

Edited and translated by Robin Schfer

Foreword by Roger Moorhouse

Blood, Dust and Snow: Diaries of a Panzer Commander in Germany and on the Eastern Front, 19381943

First published by Greenhill Books, 2022

Greenhill Books, c/o Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

For more information on our books, please visit

www.greenhillbooks.com, email contact@greenhillbooks.com

or write to us at the above address.

Copyright Robin Schfer, 2022

Foreword Roger Moorhouse 2022

The right of Robin Schfer to be identified as the author of this Work has been asserted by him/her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Image credits: Wehrkundearchiv Kwasny, Michael Schadewitz, Paul Sander, Caraktre Presse et Edition

Map credit: Paul Hewitt, Battlefield-Design

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78438-830-0

EPUB ISBN 978-1-78438-827-0

MOBI ISBN 978-1-78438-827-0

Contents

The Diary of Friedrich Sander

Acknowledgements

The Editor would like to thank Dawn Monks, Joe Greenway, Oberstleutnant (ret.) Michael Schadewitz, Paul Sander, Jessica Aitken, and David Ulke for their invaluable help and assistance.

Foreword

What follows is a quite remarkable historical document. Its author, Lieutenant Friedrich Sander, was a tank commander in the Wehrmacht 11th Panzer Regiment, a unit that would fight in the Polish Campaign in 1939, in the invasion of France and the Low Countries the following year, and as part of Army Group North in the invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941. Seeing action both in the German advances on Leningrad and Moscow, that year it experienced some of the heaviest fighting that the new Eastern Front had to offer.

Lieutenant Sander, for his part, was in many ways rather unremarkable. Born during the First World War in what became the Polish Corridor, he moved west with his family during the post-war chaos and was brought up in the comparative comfort of Osnabrck. Perhaps because of those early experiences, he shared the nationalist zeitgeist, and was a member of various patriotic organisations, before joining the Nazi Party and SS in 1934, during the first rush of enthusiasm for Hitler and the Third Reich. Conscripted in 1937, he was evidently sufficiently gifted at soldiering to be made an officer two years later, on the eve of war.

So far, so ominously familiar. Yet a couple of aspects of Sanders character set him apart: he was not only an acute observer of his surroundings the situations in which he found himself and the people with whom he mixed he was also a gifted writer, who set down his experiences with clarity and no little humour. It is these qualities, I suggest, that raise Sanders diary to the status of a document of genuine historical interest.

Apart from a short prelude in the camp at Sennelager, near Paderborn, most of Sanders diary is concerned with Operation Barbarossa, the German attack on Stalins Soviet Union, which commenced on 22 June 1941. To a large extent, Barbarossa named after the twelfth-century German king, Frederick Barbarossa was the defining conflict of the Second World War in Europe, particularly when one recalls that fully four out of every five German soldiers who died in the Second World War were killed by Stalins Red Army. Barbarossa certainly represented a step-up in scale from all that had gone before, dwarfing the French, Polish and Scandinavian campaigns in the number of men and machines engaged, with over 3 million Axis troops and 6,000 armoured vehicles advancing along a 1,500-mile frontier, which stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea.

One of those armoured vehicles was the Panzer 35(t), commanded by Friedrich Sander. Built in pre-war Czechoslovakia by Skoda Sander referred to his tank affectionately as a Skoda Super Sport the 35(t) was a light tank that shared some developmental DNA with the ubiquitous Vickers 6-ton tank of 1928. More than 200 35(t) tanks had been purloined by the Germans following their invasion of Bohemia and Moravia in the spring of 1939, and they had been pressed into service in Poland and in France, despite being obsolete.

That obsolescence was not unusual Wehrmacht ranks in 1941 also featured numerous Panzer Is and IIs, which were similarly out of date but it could be perilous for the men that crewed them. Not only did the 35(t)s of Sanders regiment suffer from higher attrition rates, due to frequent breakdowns and a lack of spare parts, they were also easily mistaken for the Vickers-derived Soviet T-26s. More seriously than that, the 35(t) was greviously undergunned when faced with the new generation of Soviet tanks, particularly the T-34. It was little surprise, perhaps, that Sander would complain already in November 1941 that his company did not possess a single operational tank; all of them had fallen foul of enemy action, mines and mechanical breakdowns. Thereafter, in the assault on Moscow, Sander and his men would be deployed as humble infantrymen; what one might call a Panzer-Regiment zu Fuss.

Just as Germanys military might was tested to destruction that year, so the ideological assumptions that travelled with its soldiers were increasingly tested too. It is often assumed out of ignorance, or an extrapolation from the comparative civility of the French campaign that the atrocities committed during the GermanSoviet war were the result of some sort of cumulative barbarisation; a spiralling of tit-for-tat crimes. Yet, as Sanders diary demonstrates, many German soldiers were already fully formed in their Nazi world view before they even set foot on Soviet soil. Sander himself is a good example of this. Whether he was observing the local peasantry or assessing the fighting resolve of his enemies, he saw the world unequivocally through the distorting lens of Nazi race theory. Even in his lighter moments, race intruded, such as when he saw a pretty girl and then chastised himself for falling in love with a Russian.

This might appear trivial, but it shows the penetration of racialised thinking. Other, more sinister, examples abound. Red Army soldiers were routinely derided by Sander as primitive or uncivilised, criticised for their cowardice in playing dead to attack from the rear, and earned only grudging respect for their tenacity under fire and their unwillingness to surrender lightly. And, one should remember, such underhand tactics feigning death or pretending to surrender often served the Germans as the justification for massacres of enemy prisoners, spurred by a moral and racial righteousness.