Table of Contents

For Danievie, Elliott, and Liam

The book sold well, we understand,

Although the cover itself would command

A buyers attention: a large, abstract bee

Crushing a butterfly with a typewriter key.

John Kennedy Toole, from The Arbiter (unpublished)

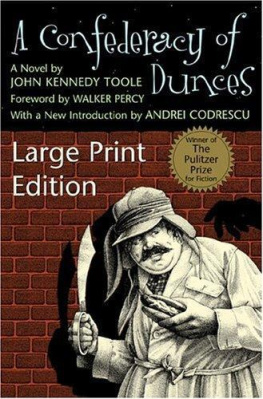

Introduction

The life and death of John Kennedy Toole is one of the most compelling stories of American literary biography. After writing A Confederacy of Dunces, Toole corresponded with Robert Gottlieb of Simon and Schuster for two years, exchanging edits and commentary. Unable to gain Gottliebs approval, Toole gave up on the novel, determining it a failure. Years later, he suffered a mental breakdown, took a two-month journey across the United States, and finally committed suicide on an inconspicuous road outside Biloxi, Mississippi. Years later, his mother found his manuscript in a shoebox and submitted it to various publishers. After many rejections, she cornered author Walker Percy, who found it a brilliant novel and facilitated its publication. It became an immediate sensation, winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1981, twelve years after Tooles death.

Since then, A Confederacy of Dunces has been hailed as the quintessential New Orleans novel. As many New Orleanians attest, no other writer has captured the essence of the city more accurately than Toole. And to this day the city celebrates its honored author. A statue of the protagonist, Ignatius Reilly, stands outside the old D. H. Holmes Department Store. Characters from the book make Mardi Gras appearances. And any reader of the novel who visits the French Quarter will certainly smile at the ubiquitous sight of a Lucky Dog cart.

But the novel exceeds the confines of regionalism. While Toole roots the characters and the plot in New Orleans, his narrative approach reflects influences from British novelists Evelyn Waugh, Kingsley Amis, and Charles Dickens. Within American literature Toole is closer to Joseph Heller and Bruce Jay Friedman than he is to iconic Southern writers Flannery OConnor and William Faulkner. In the scope of Southern literature, Confederacy seems an aberration. But within the scope of the modern novel, it is at home in its dark humor and acerbic wit.

Its continued success offers the most powerful testimony to its ability to reach past the bounds of that swath of land between Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River. To this day, it continues to garner readers. It has been translated into more than twenty-two languages and remains in print all over the world. Teachers and professors use the novel in their classes, from high school lessons on satire to graduate courses in creative writing. Plans for a film version of the book have been in development since its publication. And it recurrently appears on the best of lists periodically published in popular media. Notably, author Anthony Burgess places A Confederacy of Dunces alongside For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Catcher in the Rye in his New York Times article Modern Novels; the 99 Best. Clearly, A Confederacy of Dunces is more than a humorous romp through a Southern city; it is a classic of modern literature.

And its place is rightly earned. In the foreword to the novel, Walker Percy describes it as a compilation of Western thought and culture, from Thomas Aquinas to Don Quixote to Oliver Hardy. He considers the menagerie of characters a crowning achievement. And he recognizes it as a comedy that exceeds mere humor and ascends to the highest form of commedia. But as Percy celebrates the great accomplishments of the novel, he grapples with the detectable sadness in the book, one that is rooted in the biography of Toole. Percy writes, The tragedy of the book is the tragedy of the authorhis suicide in 1969 at the age of thirty two. Henceforth, readers of Confederacy have negotiated this intriguing paradox of the tragicomedy; the readers laughter is never far from the tinge of sadness in remembering Tooles tragic end. More so than most novels, A Confederacy of Dunces prompts the reader to ponder the life and death of the author. And while his suicide is well known, his personality, his struggles, and his triumphs, in essence, his life has hitherto remained an obscure entry within the collection of biographies of twentieth-century novelists.

Some critics may defend Tooles marginal place within the canon of American literature. Having only one novel of merit, he is easily dismissible as a one hit wonder. While talented, he does not provide scholars with a breadth of novels to dissect. But such criticism has rarely quelled biographical interest in Harper Lee, Emily Bront, or Margaret Mitchell. And if we base our measure on quality, then the prolific writer has no more value within the literary canon than the individual who composes a single masterpiece.

In fact, interest in Toole has never waned since the publication of

Confederacy. As early as 1981, writers and scholars recognized the remarkable story of his life and its place within literary history. Until her death in 1984, Tooles mother, Thelma Toole, received many requests of permission to write a biography of her son, and she patently declined them. But in her reply to the request of James Allsup, an acquaintance of Toole from his army days in Puerto Rico who had since become a professor of English, Thelma outlined the essential rigors required of any Toole biographer:

Dear Mr. Allsup:

Your qualifications to write a biography of my son are excellent, but, if I granted your request this is what it would imply: you would have to live in my home for several months, perhaps, a year, perhaps, more; then, you would have to read carefully a wealth of material, pertaining to my son; then, you and I would decide what to use, what not to use; then, we would begin collaboration.

After listing these stipulations, she politely declined his request.

To any established professor, Thelmas hypothetical expectations would be absurd. But she accurately portrays the difficult grounds a Toole biographer must navigate. Even for his mother, who usually appeared quite omniscient in regard to her son, composing the narrative of Tooles life was a daunting task. She attempted on one occasion but got no further than a few pages.

Such challenges became painfully evident in the first biography of Toole, Ignatius Rising: The Life of John Kennedy Toole, written by Ren Pol Nevils and Deborah George Hardy. While Nevils and Hardy provide readers with an unprecedented resource in that they published the correspondence between Gottlieb and Toole, albeit without Gottliebs permission, they also depict Toole as a man suffering from an Oedipal complex, suppressed homosexuality, alcoholism, madness, and an appetite for promiscuity. Toole becomes a caricature of the fatal artist. While some reviewers forgave Nevils and Hardy for their indiscretion, many friends of Toole found the book insidious. Tooles friend Joel Fletcher angrily observed, The authors have so carelessly written half-truths and untruths about a friend who is not here to defend himself.

Troubled by the sensationalism in Ignatius Rising