With thanks to Cynthia Watters, Bill Grisham,

and Anne-Marie Schaaf for encouraging us to visit

the Orkneys and to David Lea for his enthusiastic and

informative tour of the islands.

C. A. and A. A.

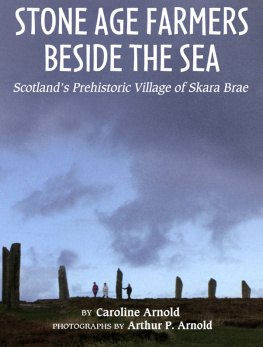

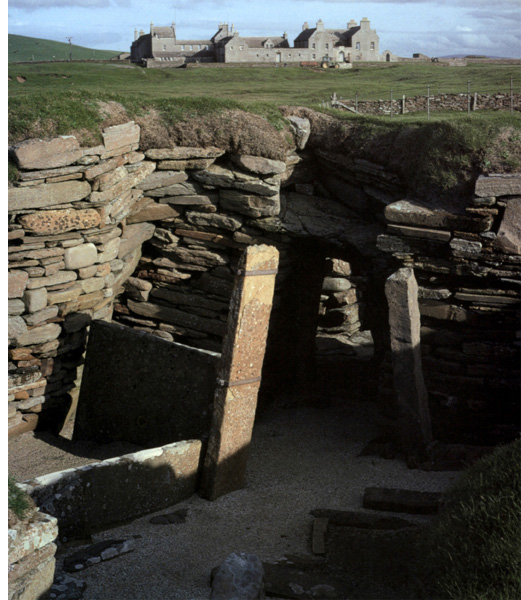

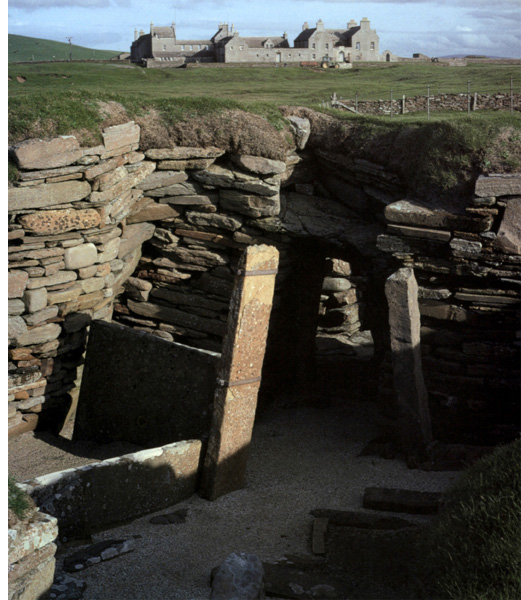

Title page: View of Skaill House from Skara Brae

Page 2: The Old Man of Hoy (on the Orkney coast)

Photo credits: AnneMarie Schaaf, , left;

Caroline Arnold, , bottom right.

Text copyright 2013, 1997 by Caroline Arnold

Photographs copyright 2013, 1997 by Arthur P. Arnold

All rights reserved.

Published by StarWalk Kids Media

Except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and

articles, no part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner

whatsoever without written permission from the publisher. Contact:

StarWalk Kids Media, 15 Cutter Mill Road, Suite 242, Great Neck, NY 11021

www.StarWalkKids.com

ISBN 978-1-623348-07-6

CONTENTS

Guide

A wide embankment surrounding Skara Brae provides views into the ancient dwellings.

O n a windswept island at the northern tip of Scotland, thick stone walls lie half buried by the edge of the sea. They are the remains of Skara Brae (pronounced Scar-a Bray), one of Europes oldest known and best preserved prehistoric villages. Five thousand years ago ancient farmers tended livestock and tilled the earth on land surrounding the village. They also hunted wildlife and fished along the coast. Their houses, built of sturdy stone, were clustered in a compact unit and joined along an inner passageway. They were the heart of a close-knit agricultural community and may have been home to as many as twenty families at one time.

People lived at Skara Brae for about six hundred years, from 3100 to 2500 B.C. After they left, wind blew sand from the surrounding dunes over the village and buried it. For thousands of years Skara Brae was forgotten. It was not until its discovery almost 150 years ago that the life of its inhabitants became known once again.

Today visitors to Skara Brae can explore the remains of the village and see many of the ancient objects found during its excavation. No other place in northern Europe provides such a complete picture of life in the Neolithic, or New Stone Age, a period of human history when people made tools with stone or bone and began to live in settled communities.

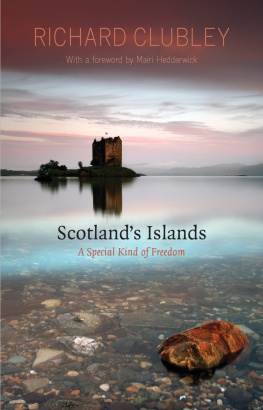

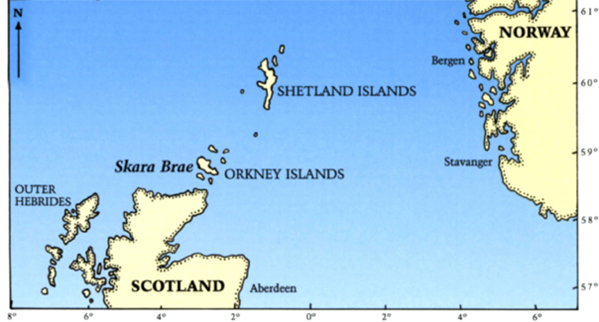

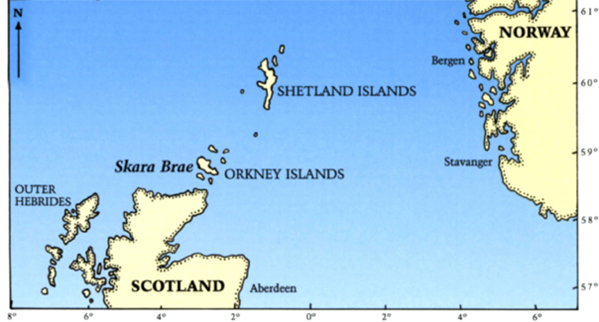

Skara Brae is in the Orkneys, a group of more than seventy islands at the northern tip of Scotland. The islands have been continuously inhabited for more than five thousand years, and the landscape, which is dotted with the remains of ancient dwellings, tombs, and other structures from the past, is an archeologists paradise. Prehistoric sites in the Orkneys range from the giant standing stones of Neolithic times to the ruins of Viking settlements built in the eleventh century A.D.

The village of Skara Brae was built near the shore of a bay on the west side of one of the largest Orkney islands called Mainland. Five thousand years ago the shoreline was more distant and separated from the houses by sand. Wind and erosion have destroyed the dunes, increasing the size of the bay, so its shore is now nearly at the edge of the village. The name Skara Brae comes from Scottish words meaning hilly dunes.

The ruins of Skara Brae face the Bay of Skaill.

The standing stones of the Ring of Brodgar were erected during the same period that people were living at Skara Brae.

The weather in the Orkneys is often wet and windy, and in the winter of 1850, a series of violent storms battered the islands, pounding them with fierce waves and gale force winds. One of these storms was so severe that it blew away the grass and sand from a high dune on land owned by William Watt, the Laird of Skaill. (Laird is the Scottish word for lord, a British hereditary title.) When the storm subsided, William Watt went out to inspect the damage to his property. As he crossed the land that separated his fields from the sea, he saw that the wind and waves had exposed the remains of an ancient village, which had been buried beneath the sand. For the first time in more than forty centuries, the dwellings of Skara Brae were exposed to the open air. As William Watt uncovered the ruins he discovered more stone walls, furniture, stone and bone tools, pottery, beads, and other objects. The sand and surrounding embankment had protected the houses and the items in them so well that many were in almost perfect condition.

Between 1850 and 1868 William Watt excavated four of the houses at Skara Brae and collected a large number of stone tools and other objects that are now in the collection of the British Museum. Even though he was not a trained archeologist, William Watt knew that the ruins on his property were unusual and provided important clues to how some of the earliest inhabitants of the islands once lived.

The manor house of the Laird of Skaill stands about a quarter of a mile (0.4 kilometers) from the ruins of Skara Brae.