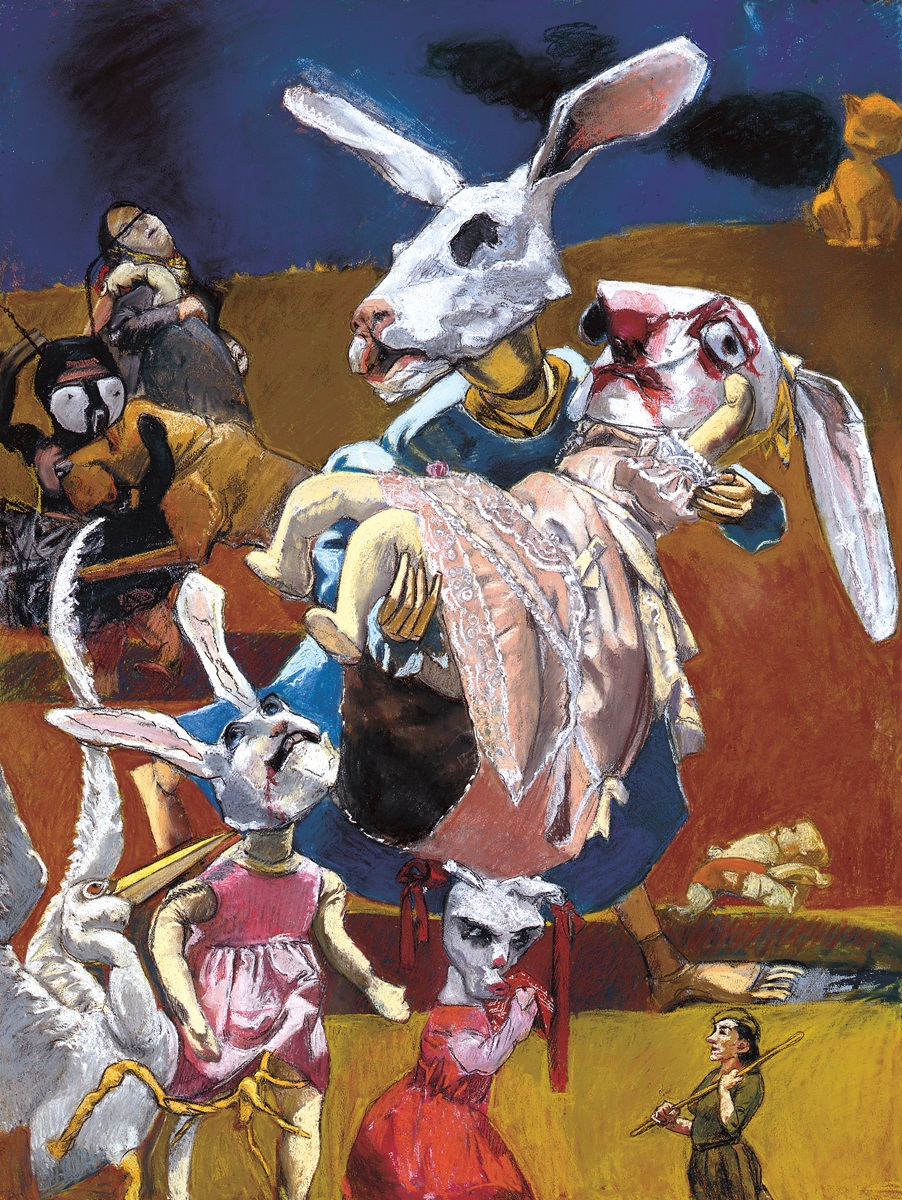

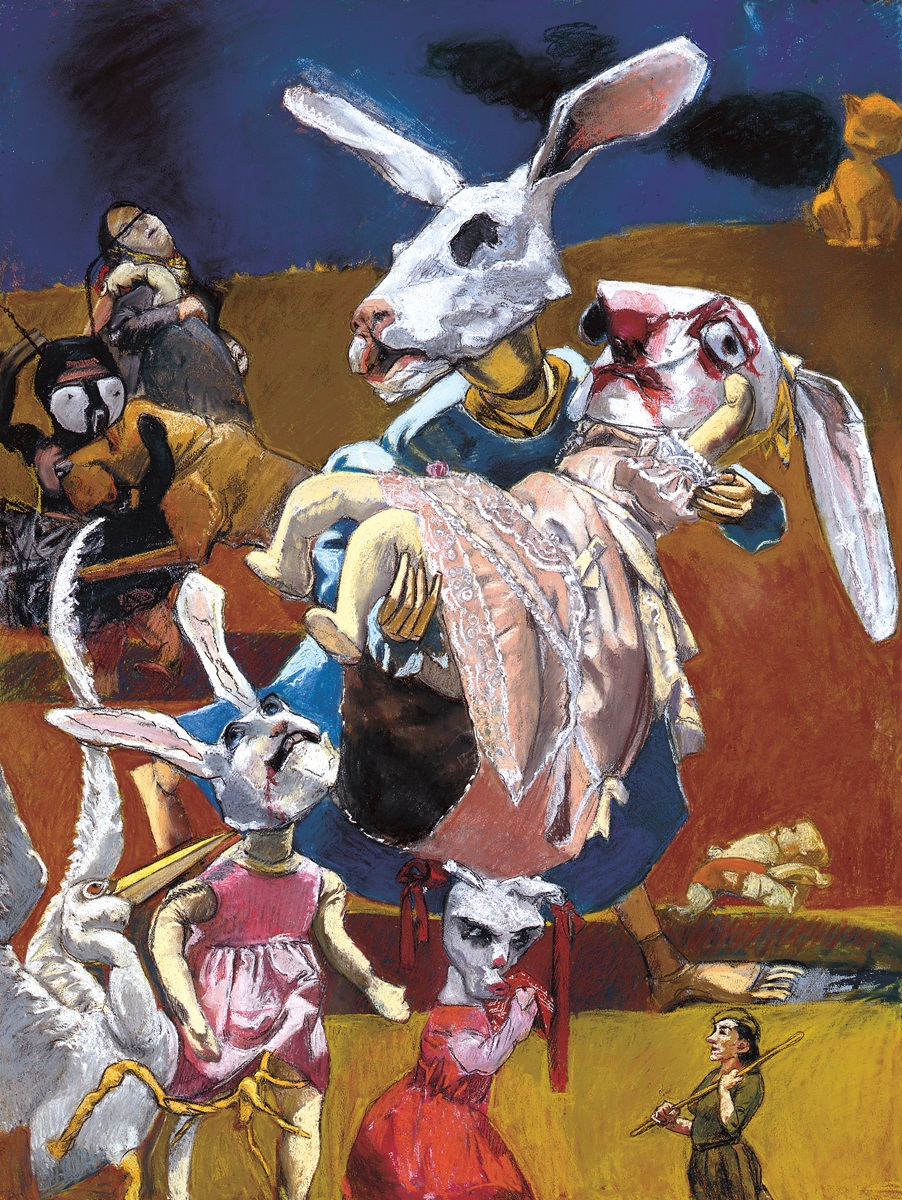

Paula Rego, War, 2003

To Beatrice, with love & gratitude

CONTENTS

Leonardo da Vinci, Sections of the Human Head and Eye 149093

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Paula Rego:

Nursery Rhymes

Seeing Ourselves:

Womens Self-Portraits

Mythomania:

Tales of Our Times, From Apple to Isis

Women Artists:

The Linda Nochlin Reader

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

A drawing Leonardo made of a section through the skull rejects the classical and medieval models of the faculties which allotted different sections of the brain to intellect and fantasy; instead, the artist connected empirical vision from the eye to reasoned judgment and imaginative recreation, along a continuum leading to memory.

Their intuitions have been corroborated by recent findings in cognitive psychology: the same synapses of the brain fire whether you are remembering something that has taken place in your own experience, recalling a scene that you once read or saw in a film, or dreaming up an event that has never taken place. In relation to art and artists, this research is especially significant. This new understanding of consciousness confirms a defining dynamic of creativity itself: that the combinatory imagination at work does not engage separate faculties, but demands similar activities from the brain visualizing, modelling, patterning, linking and building concepts and images. When making something, memories, empirical observation and make-believe continually overlap and interact.

My interest in art and artists arises from a lifelong commitment to understanding the imagination and the part it plays in acquiring knowledge and understanding, for good and ill. Artists have long occupied and planted this territory indeed, their involvement with the unseen and the unverifiable goes back to images of deities and monsters on cylinder seals and Greek pots, continues strongly with the Abrahamic religions and has reinvigorated contemporary image-making as well as stirring up fresh outbreaks of image-breaking.

My first taste of art as a marvellous and different realm was at Kettles Yard in Cambridge, in the early sixties. H. S. Jim Ede was still alive when I was growing up in a village five miles away, and he was legendary for his open house, his collection of artists including Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth and his vision of living with art, in the low-lying cottages he had turned into an intimate, personal museum. During my gap year (not yet known as such), I was enrolled in the Cours des trangers at the Sorbonne in Paris, a city where contemporary art was far more alive and sought-after than in London in those days. The Brancusi studio was still at the address where the sculptor had worked and was inspiringly rich in associations and dust; at the Atelier 17, S. W. Bill Hayter was teaching a stream of young artists from all over the world the original processes he had developed for printing in layers of colour; the city was packed with galleries, several of them specializing in various avant-gardes. Artists many from Greece and Latin America were bringing a different language of light and movement to contemporary sculpture (beside Calders mobiles, there were Takiss oscillating wands). These months in Paris, before I went up to Oxford in 1964, began my apprenticeship in modern and contemporary art. I had wide eyes and was finding out how fabulously, utterly involving it could be to spend time looking at things people made.

Several of the writers I most enjoy have engaged passionately with art and artists. Some were professional critics (Denis Diderot, Charles Baudelaire, John Ashbery), while for Marcel Proust, Edith Wharton, Wallace Stevens, Gertrude Stein, Czeslaw Milosz I could go on writing about art occupied their word-worlds more than has perhaps been acknowledged. The reasons for this oversight might include suspicions that a literary approach subordinates the artwork in question to another discipline and consequently denatures it, and also that writing about art is not proper criticism, but an accompaniment, as a pianist plays for a singer.

I dont want to make high claims for my own attempts, but I do wish to argue for writerly ways of exploring art, as developed in literary tradition. When I write about artworks and the artists who made them, I try to unite my imagination with theirs, in an act of absorption that corresponds to the intrinsic pleasure of looking at art. Since the Greeks, ekphrasis has offered a way of capturing visual experience in words but while I believe in close looking, description is not enough. I like to explore above all the range of allusions to stories and symbols; not to pin down the artwork as if it were a thesis or a piece of code, but to touch the springs of the works power. Art-writing at its most useful should share in the dynamism, fluidity and passions of the objects of its inquiry.

The inner lives of women have also fascinated me, and the book includes essays on several key figures in contemporary art and performance. The first artist to ask me to write for a catalogue was Helen Chadwick, for her show at Londons Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in 1986. The task involved many wonderful conversations at her studio, in our kitchens, at art galleries and science museums, listening to her flow of surprising, inspired ideas and rummaging through archives of her source material. I was used to being on my own, writing, and I found I really enjoyed the experience of communing with an artist. The contact with Helen, with her originality and verve and daring, was exhilarating. When she died in 1996, I felt her loss very sharply. Hers was a rare creative force.

The Greeks idea of ekphrasis stressed thick description and dramatic evocation Botticelli was able to recreate a painting, The Calumny of Apelles, from Plinys detailed word-picture of the lost work from antiquity. However, ekphrasis is not only the transposition of an image into words. It presumes that a work of art is active: Homers description of the shield of Achilles in the Iliad reads like an epic film, with the figures in turmoil, the action filled with sound and fury and pastoral moments of quietness, too. The work of art, the Greeks thought, should possess enargeia, or shining vitality, the enhanced vividness which, when present in a work of art, magnifies it not in size but in impact, the quality that makes your eyes widen as the image seems to fasten on your gaze. The Greeks admired naturalistic illusion, and identified enargeia with lifelikeness (the bunch of grapes that deceived birds; the curtain painted by Parrhasius that his rival, Zeuxis, tried to draw aside). But I recognize it as the quality of presence that fills one made thing more than another, and charges it with the power to command attention and radiate significance.

Next page