Published in 2016 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2016 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #CW16CSQ All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stanmyre, Jackie

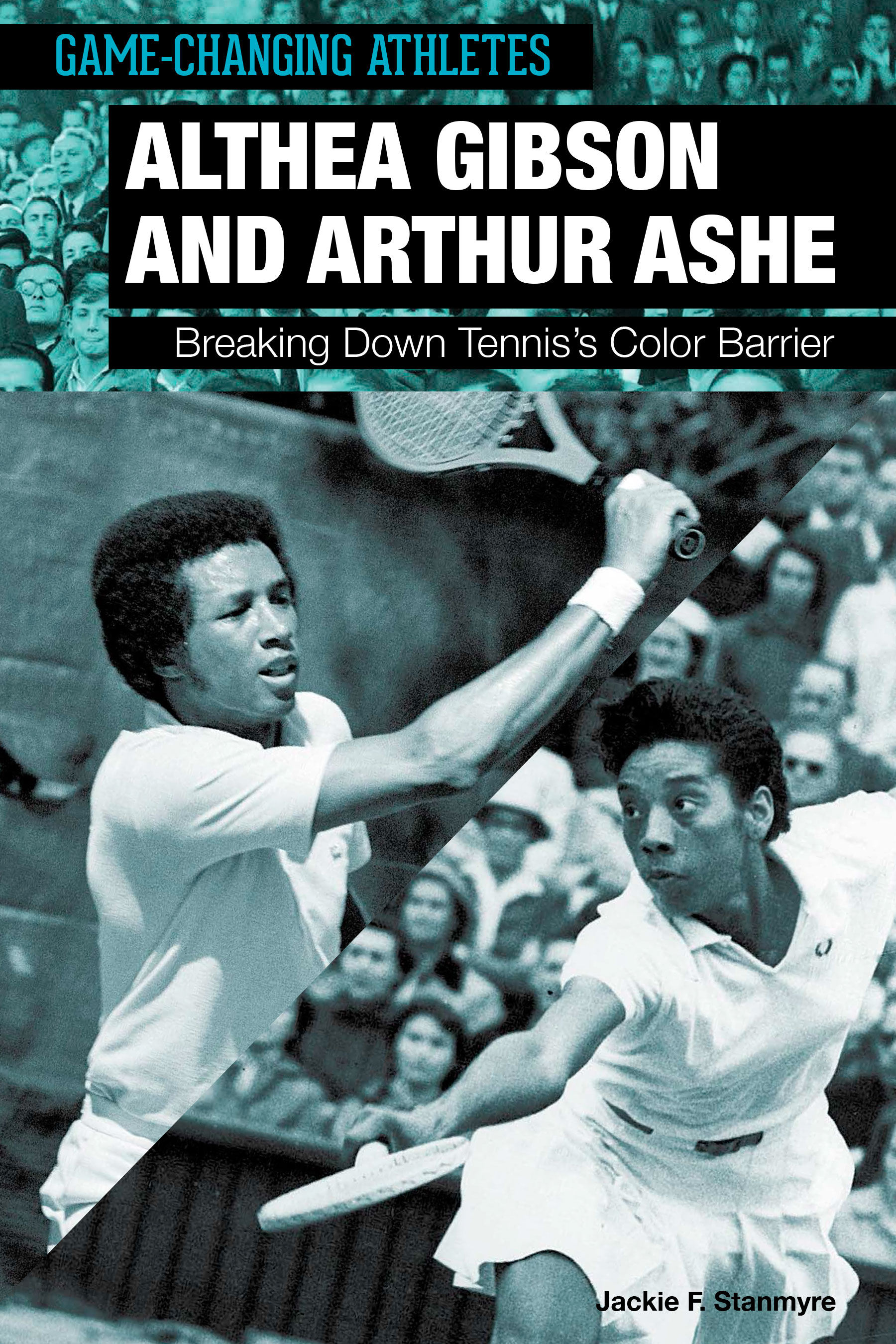

Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe: breaking down tenniss color barrier / Jackie Stanmyre. pages cm. (Game-changing athletes)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-5026-1037-9 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-5026-1055-3 (ebook)

1. Gibson, Althea, 1927-2003Juvenile literature. 2. African American women tennis players BiographyJuvenile literature. 3. Ashe, ArthurJuvenile literature. 4. African American tennis players BiographyJuvenile literature. 5. Tennis playersUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature. I. Title.

GV994.G53S68 2016 796.3420922dc23 [B]

2015027433

Editorial Director: David McNamara Editor: Fletcher Doyle Copy Editor: Rebecca Rohan Art Director: Jeffrey Talbot Designer: Joseph Macri

enior Production Manager: Jennifer Ryder-Talbot Production Editor: Renni Johnson Photo Research: J8 Media

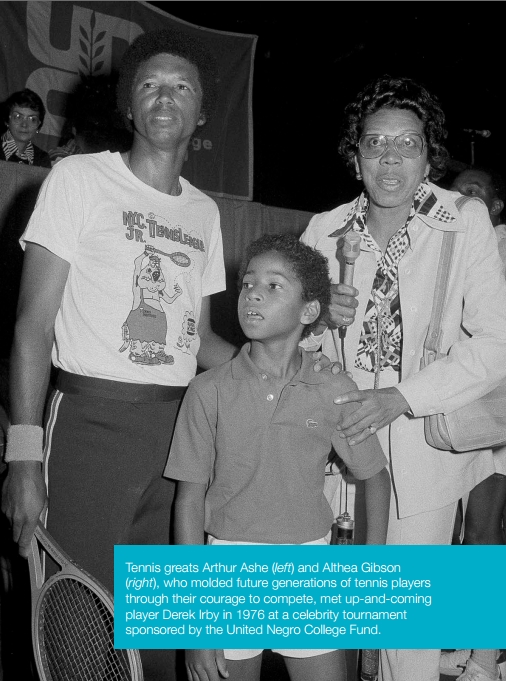

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of: Norman Potter/Express/ Getty Images, front, back cover and throughout the book; CBS via Getty Images, Hulton Archive/Getty Images, front cover; AP Photo, 5, 28, 54; Gordon Parks/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images, 8; File: Althea Gibson/New York World-Telegram and the Sun staff photographer: Fred Palumbo/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division/New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection/ http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c14745 NYWTS.jpg /Wikimedia Commons, 11; AP Photo/ Elise Amendola, 12; File: Johnson House Lynchburg Nov 08.JPG /Pubdog/Wikimedia Commons, 15;

AP Photo/Marty Lederhandler, 18, 74; Top Foto/The Image Works, 24; AFP/Getty Images, 31; Keystone/ Getty Images, 34; Reg Speller/Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, 42; Phil Greitzer/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images, 44-45; AP Photo/Harry Harris, 48, 83; Mike Lien/New York Times Co./Getty Images, 57; Walter Kelleher/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images, 61; Gerry Cranham/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images, 64; Tony Triolo/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images, 68; Focus on Sport/ Getty Images, 71; AP Photo/George Wildman, 79; Ron Burton/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, 84; John Pedin/NY Daily News via Getty Images, 87; Matthew Stockman/Getty Images, 90; File: Serena and Venus Williams (9630777503).jpg/Edwin Martinez ( http://www.flickr.com/people/22705753@N06 ) from The Bronx/Wikimedia Commons, 93; File: Althea Gibson statue.jpg/Sculpture: Thomas Jay Warren/Image: DoctorJoeE/Wikimedia Commons, 95; Ivan Nikolov/WENN.com/age footstock.com, 98-99.

B efore the civil rights movement had truly begun in the United States, the athletic fields and courts were becoming a frontier for breaking down racial barriers. The discriminatory policies and sentiments that plagued much of the nation, however, created obstacles for leading African-American athletes. This was particularly true in tennis, a sport long known for its elite, rich, and white history.

While many competitions barred African Americans, a few integrated events provided a platform for a handful of athletes to show their worth on the courts. The struggle was long, arduous, and often took a thick skin to navigate. Two such tennis players can be credited for opening doors by combining the courage to take on those who saw them as less-than-equal with the determination to use their athletic gifts to their fullest.

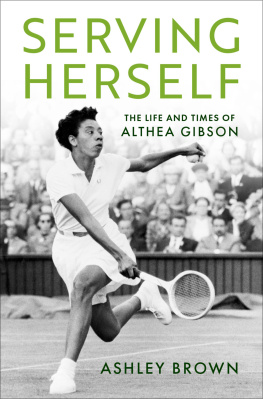

Althea Gibson, a self-proclaimed tomboy, was known in her neighborhood as the toughest competitor, boy or girl, in almost any sport. Her tennis story began after she showed a knack for paddle tennis , a court game similar to ping-pong. She gained acclaim from adults who ultimately guided her through her teenage years to opportunities that took her far from her parents home. They helped her over the hurdle of discrimination set up by naysayers who believed she didnt deserve a place on the courts long occupied only by whites. Gibson didnt fight these battles with her words, but with her tennis racket. She made it impossible for those in the highest ranks to ignore her immense talents. While her journey was anything but smooth, Gibson ultimately made it to the upper echelon of tennis, winning the US Tennis Championships (the predecessor to the US Open) and Wimbledon, among many other titles. Gibson was not an activist in the traditional sense, and rarely did she speak up about equal rights, but through her athleticism and willingness to enter into hostile environments, Gibson created opportunities for African-American athletes for years to come.

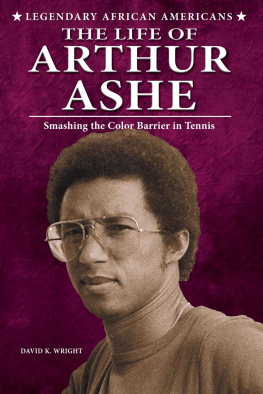

One of those for whom the door would open was Arthur Ashe. Unlike Gibson, Ashe was incredibly vocal and insightful about his experiences with racism, bigotry, and injustice. He fought his battles on and off the court, standing up for his own rights and those of others like him. Ashe became the first African-American male to be a member of the US Davis Cup team, which represents the country in international tennis competition. He also would become the first African-American male to win at Wimbledon, the Australian Open, and the US Open. Throughout his career, Ashe advocated for the rights of his fellow tennis players by helping to form the Association of Tennis Professionals . This union gave the athletes more say in their schedules and more opportunities to increase their share of the sports growing revenues. He created youth tennis programs to reach disadvantaged children, and he became a staunch and vocal opponent of South Africas apartheid policies, which suppressed blacks in that country. In his later years, Ashe became known for his role as an ambassador in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) awareness, after he was diagnosed with the disease. Ashe cared much about his success on the tennis court, but he also used it as a platform to further bring light to issues of grave importance.