Table of Contents

Contents

M y story begins in the blood-and-tears-soaked backdrop of World War II, the global nightmare that lasted six years, killing close to fifty million people and displacing millions of others. Rat-a-tat gunfire and exploding bombs, severed limbs and flattened cities, and an absence of anything life-affirming, defined those years. There was no home untouched by the war, including that of my maternal grandfather, Baburao Sirpala man who played a pivotal role in my life. We called him Papaji.

Papaji was a tall, slim and handsome man who brooked no nonsense. He owned the largest sports goods store in Rangoon, Burma. It was common then for Indians to move to Burma for a better life. The country was beautiful, bursting with tropical verdancy punctuated by golden domes of pagodas, and with bountiful markets by rivers like the Irrawaddy. The people were gentle and peace-loving.

As Burma was under British rule, Indians anglicized their names. Thus, Baburao Sirpal, Papaji, became B.R. Sir Paul, just as Makkad changed to Maker and Kakkar to Kaicker. Only my grandmother remained Durga, inappropriately, as she was always dressed in a white sari and was short and frail.

Papaji, though strict, lavished attention on his daughters. My mother, Kaushalya or Mary, grew up with a convent education, wore a longyi like Aung San Suu Kyi and spent her vacations at the familys sprawling weekend home in Mandalay, Burmas second important city. My mother always spoke fondly about their Mandalay visits. On her eighteenth birthday, Papaji gifted her with a Cadillac, which she crashed on her first drive out.

It was a happy and affluent family life until 1942, when the Japanese came a-calling as a fallout of World War II. Like an ostrich with its head buried in the sand, Papaji did not take the invasion seriously, thinking that his wealth and contacts would protect him. It was only when Japanese tanks rumbled down the streets and the city began to empty that he realized that he, too, had to flee to India. What was still busy and bustling was the port, where the last ship was getting ready to sail.

Papaji packed as many family valuables as he could into large steel trunks and brought them to the docks. He bought first-class tickets for the familylook at the pride and optimism!while there were still a few hours for departure. At the docks, the loaders, taking advantage of the situation, asked for Rs 100 per trunk. Papaji blew a fuse. A hundred bucks in the 1940s was perhaps equivalent to Rs 10,000 in todays value. I have so many servants at home, he hollered. I dont need you guys. Ill call my staff from home to load.

However, pandemonium at the docks increased. The throngs, shoving and screaming, their survival at stake, started forcing themselves on to the ship regardless of whether they had a ticket or not. And then well before the official departure time, the ship hooted its last call. Punctuality is not a priority when a city is under attack. Papaji and his family were pushed aboard just as the ship withdrew the gangway to set off on its twenty-four-hour journey to India.

On board there was mayhem. Papaji and his family could not even get a cabin, forget a first-class one. They lay on the floor of the cold, open deck with no blankets and with hundreds of other people crying around them. Imagine leaving behind your lifes earnings in a city fading in the distance, together with all the happy memories, including a Cadillac that would never again unite with its original, longyi-wearing owner.

The voyage from Rangoon to Sialkot was a long one for Papaji and his family, and not the last odyssey either. After the ship took them to Chennai (then Madras), they took a train all the way up and west to Sialkot, as it was a hub for the sports goods industry. Papaji built his business up againrupee by rupeein undivided India. But there was more pain and displacement to come.

It came to light that Papajis sister had not made it to the ship in Rangoon. Having to fend for herself, she had wrapped all her jewellery around her body, under her clothes, and walked. She walked from Burma to Amritsar through Bangladesh (then East Pakistan). Her feet were shredded by the time she reached Punjab.

Then Partition happened. Papaji and his family walked thousands of miles from Sialkot to the newly carved Indian territories. Along the way they saw people being slaughtered, they saw babies and children crying, and so much other suffering. The family made it to Delhi.

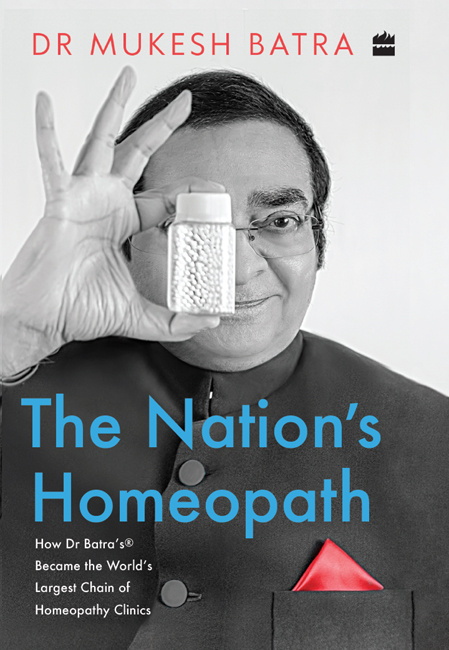

My mother eventually studied medicine at Lady Hardinge Medical College and moved to Lucknow after marrying my dad, Dr M.C. Batra, a homeopath. Papaji settled in Agra and built his life from scratch for the third time, this instance with a leather goods business. First sports and now leather, both demanding resilience and toil, were apt metaphors for my grandfathers life.

And on 1 July 1951, I was born in Lucknow, the son of a mother who was an allopathic doctor and a father who was a homeopath, making me a product of mixopathy.

I was the oldest of three boys. My younger brother was Rakesh and my youngest brother Navkesh, a name that made no sense. But names didnt have to in those days. Parents had too much on their plates to worry about their kids names. We only had to sound like brothers, which Mukesh, Rakesh and Navkesh certainly did. And at least we were not called Mogambo or something, like Amrish Puri in the film Mr India (1987).

We lived on the upper floor of a rickety old building in Lucknows fashionable Hazratganj area named after Nawab Amjad Ali Shah, who was respectfully addressed as Hazrat. The buzz around Hazratganj did not change the fact that our building was in poor condition. My first close call with death occurred here, when I was a baby. My uncle saw me crawling towards the balcony and pulled me away, perhaps driven by some intuition. Seconds later, the balcony crashed three storeys to the ground. Events since have led me to believe I have a cats nine lives (and hopefully the same feline grace). My life, at such times, has seemed like a 1970s movie, except two of these events took place in the 1950s.

The second close call occurred when I got lost in a mela. It was 1954 and my parents had taken me to the Maha Kumbh in Prayagraj (then Allahabad). I was three. Disorderly crowds in an open space can be a recipe for disaster. Soon enough, a stampede ensued. People ran over and around me like galloping horses. Nearly 800 people died in the crush, and I could easily have been one of them. Luckily a friend of my fathers, a strapping homeopath named Dr Sindhi, found me and hoisted me upon his shoulders. He carried me through the surge of people panicking on all sides.

Not much later, my parents packed me off to Agra to live with Papaji and Mataji, which is how we addressed my grandmother. They had been alone after marrying off their two daughters: my mom and her sister Savitri (Savy). They lived in Hing ki Mandi, a congested area. Agra was a blue-collar industrial town, a hub of the leather and marble trades. Save for the Taj Mahal and Fatehpur Sikri, it lacked the sophistication of Lucknow.

My academic year was spent in Agra, at St. Anthony School in Cantt (the cantonment area), and holidays in Lucknow. This meant a once-in-a-year round trip between the two towns. I would be sent on the train journey accompanied by anyone travelling in the same direction, strangers included.