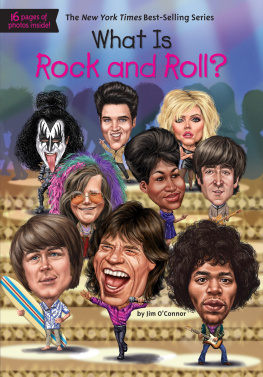

INDIA PSYCHEDELIC

THE STORY OF A ROCKING GENERATION

SIDHARTH BHATIA

HarperCollins Publishers India

To

Almona, Aliya and Rhea

Each one a rock star!

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me)

Between the end of the Chatterley ban

And the Beatles first LP.

Philip Larkin, Annus Mirabilis

The times they are a-changin

Bob Dylan

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION: THOSE WERE

THE DAYS

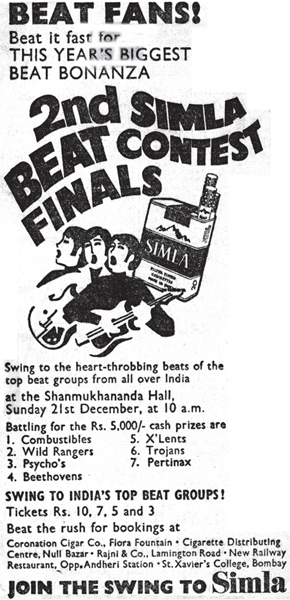

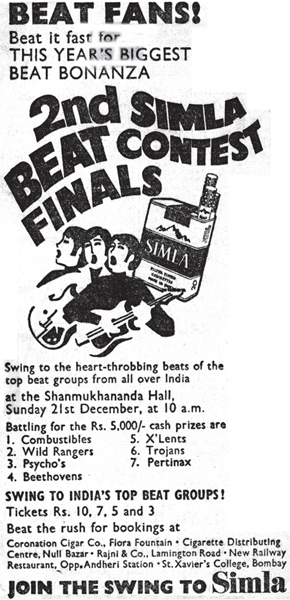

A PACK OF youngsters clustered outside the Shanmukhananda Hall in Bombays Kings Circle area, waiting impatiently for the doors to open. They were dressed in the fashion of the day, their batik T-shirts and bell-bottomed pants a cheerful, colourful splash on that pleasant Sunday morning. Passers-by staring at the long-haired boys and brightly attired girls probably wondered which species these strange creatures belonged to. Some of the assembled young people looked back equally wonderingly at the staid locals going about their morning chores. In this conservative neighbourhood, though, it was the young outsiders who were the misfits. But mostly, their minds were on what was to come once the doors opened. It was the finals of the Simla Beat Contest, where the best beat groups from all over the country would play and sing their hearts outa much-awaited event for music freaks. The year was 1971.

For a teenager about to move on to college, being there was exciting. Though my memory of that day is hazy, I like to think there was an electric buzz in the air, not least because of all that grass perhaps being smoked. This was highly unlikely though, because only diehards would light up a spliff at 10 a.m., but the idea adds that much more colour to the story. The vibe was groovy, it was a time of wild clothes and wilder hair, of rock songs that spoke of angst, love and other universal themes, of uninhibited dance and musica time also of innocence.

Though many other rock competitions were held those days, this was the biggest of them all. In its five-year existence, the Simla Beat Contest had become the premier event for bands and fans alike. The local qualifying rounds were rigorous and only the best bands from around the country made it to Bombay. The names are long forgotten, but evocative. The Fentones (Shillong), Purple Flower (Ahmedabad), Velvette Fogg (Bombay), Eruptions (Cuttack). Winning any of the prizesbest group, best original composition, even best drummercould mean not only much-needed cash but also recognition and possibly a recording contract.

Such is our lack of interest in archiving our history that there is very little information available on the Simla Beat Contest today; the Internet throws up some mentions here and there but those are personal stories. Printed records cannot be found easily. Newspapers in those days disdained writing about popular culture and certainly beat music and rock groups were beyond the pale. Only JS magazine, the chronicler of youth culture of the time, covered the contest in detail, declaring it a success and thanking ITC for organizing it.

Simla was a brand of cigarette launched by the India (then Imperial) Tobacco Company. The menthol-tipped cigarette, pitched as light and thus less harmful, was specifically aimed at young smokers; it was also, quite literally, cool, thanks to the menthol. Sadly, in the corridors of the century-old company, ITC, there is no institutional memory of the event. A senior official at ITC said he could find absolutely no records of any such promotion and had no personal memories of it either, though he had worked in the company for over thirty-five years. The irony of it all is that the two records that were produced after the contests in 1970 and 71 are now collectors items.

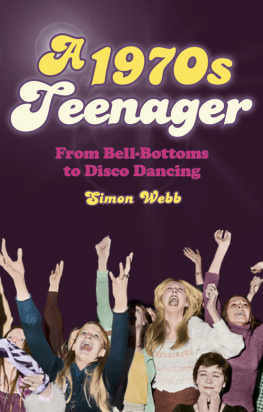

A younger reader today would find the idea of his parents attending a rock concert in the morning astonishing, since we live in a time when nostalgia is but a few years old and anything beyond a couple of decades is ancient history. The thought of something so hip as rock music in India, to say nothing of rock concerts, in the Jurassic 70s, seems outlandish. India circa the 1970s now seems like a distant and somewhat weird planet, occasionally surfacing in Hindi films that parody the kitschy fashions of the time. Fraying photo albums show shaggy-haired boys and girls in bell-bottoms and maxis but little else is known about the alternative scene of the period.

India of the 1960s and 70s was certainly not all about groovy beat groups and far-out fashions. The swinging 60s that swept Britain and the West in general barely trickled in here. India was too busy trying to survive. It was a testing time for the young nation as it struggled to cope with overwhelming odds that threatened it from within and without. It is an overused clich to say that India was in the throes of change, but the decade and a half between 1960 and the mid-70s was truly a period of extraordinary convulsions. Through most of those years, India lurched from crisis to crisis, each one more severe than the previous one. The country fought three wars between 1962 and 1971; dealt with a famine with which it coped, thanks to food imports (for which it could not pay); suffered from chronic food shortages which were met only through charity from the rest of the world, mainly the US which never let us forget it; and faced a severe energy crisis after the 1973 oil shock.

By the early 1960s, the idealism and fervour generated by Independence was gone. It was clear that the end of the Raj hadnt addressed our endemic problems of poverty, inequality and corruption. The old rulers had given way to new ones who seemed equally unconcerned about the man on the street. The Nehruvian projectof self-reliance, nation building and communal harmonyheld strong, but most of the social and economic challenges appeared overwhelming. When Indias first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, died in the wake of Indias humiliating defeat in the war with China, for a while it seemed that the nation itself would not survive. Though the predicted collapse did not come about, it was a precarious existence and India was often written off as a country whose very survival was in doubt.

As the 1960s segued into the next decade, some progress became visible. But many familiar challenges and problems remained: food shortages, natural calamities, low growth, political and social upheaval, large-scale unemployment, corruption in public life, and global pressures. The economy chugged along at a sedate Hindu rate of growth and the country continued to be considered a basket case.

It was a time of high demand but low availability. Shining India today revels in the easy availability of consumer goods, but the situation was quite the opposite at the time. Only three companies made cars and it took years to acquire a Vespa or Bajaj scooter, then the preferred mode of transport of middle-class familiesthe customer had to pay the entire sum while booking the vehicle and put himself on a waiting list. One needed extraordinary influence to get hold of a telephone, a domestic gas connection or even a milk card that allowed the holder to buy milk from a government dairy. Wheat, rice, sugar, kerosene, most such items of daily use could be bought only in limited units mentioned on a familys ration card. Some item or the otherbread, butter and suchlikewould be unavailable and even relatively well-off families had to make do without it. There were stringent regulations, such as the Guest Control Order, which put an upper limit on the number of people who could be invited to a weddingto ensure that precious food was not wasted.

Next page