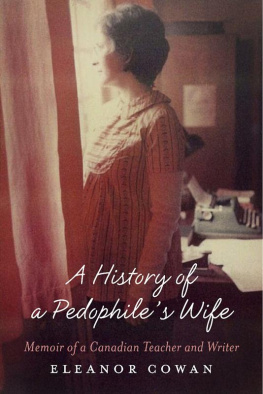

How could a mother not know? This is a question often asked about families where incest has occurred, and Eleanor Cowans gripping memoir, A History of a Pedophiles Wife, steps up with answers that are courageous and heartbreaking. Cowan grew up in Quebec in the 1950s, in a large Roman Catholic family with a lethal mix of violence, addiction, and toxic pedagogy. Cowan details the dance of a survivor moving into adulthood: one step forward towards freedom, two steps back into conditioning, until a tipping point of consciousness is reached. As her memoir makes clear, that tipping point is not just a critical mass of abuse or even a touchstone of personal growth. It requires an enlarged and feminist context, permission to know the unknowable, and language to name the unspeakable.

Cowans book is a primer in compassion, especially for those of us who were abused as children and left to struggle with legacies of distrust and rage towards our mothers. Its a vivid indictment of a mother-blaming culture that protects the very institutions that perpetuate child abuse.

Carolyn Gage, playwright, performer, director, and activist

Eleanor Cowan, a Canadian teacher, works and writes in northern Quebec.

Copyright Eleanor Cowan, 2013

ISBN: 9781483514949

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

Dedication

I dedicate this memoir to all those who have been traumatized by ridiculous religious dogma, frightened families who never knew the meaning of the word natural. May this book encourage righteous revolt so that autonomy in a real world can be experienced at last.

Acknowledgements:

I thank my children for their permission to write about our small family, and my siblings, for their encouragement.

I would also like to thank, most sincerely:

All educators the activists, writers, radio show hosts, film makers, social workers and law makers whose artistic energy turns the wheel of human evolution; Canadian writer Elaine Kalman Naves for her strong advice to write my true story as a memoir rather than fiction, and to stand behind my opinions; playwright Carolyn Gage, columnist Barbara Kay, film maker Virginia Hastings and teacher Steve Canty for reading and commenting upon my work with such thoughtfulness.

Vancouver editors, Lara Kordic and Irene Kavanagh, Montreal editor Kathe Lieber, Ontario editors Erin Stropes and Wendy Carroll and Florida editor, Marlene at Firstediting.com for invaluable skills and sensitivity while working with my manuscript.

The Yellow Door (YD Generations in Montreal ) who introduced me to two volunteer readers and thoughtful commenters, social worker Neeti Sasi and doctoral candidate, Hannah Wood.

We make our own criminals and their crimes are congruent with the national culture we all share. It has been said that a people get the kind of political leadership they deserve. I also think they get the kinds of crime and criminals they themselves bring into being.Margaret Mead

Introduction

Open Heart Surgery

I was forty years old when I was invited to a group Id never expected to join for parents of sexually abused children, the stark name uncompromising. Even at our first meeting, I was to learn about revising my vocabulary, about calling a spade a spade.

Because more women than men were present, the women were ushered to a larger space at the social services center. Worse than our numbers was the fact that I recognized many of the women finding places in the rows of rickety, collapsible chairs. As I looked around, for a jarring instant I thought I was at Mass. Restraining a bizarre impulse to genuflect, kneel, bow my head, and cross myself in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, I managed to sit down, tuck my purse under flimsy chair legs, smooth my skirt, pick up my purse again, and shuffle through it for my planner and a pen. When a hand touched my bare arm, I looked down to see a familiar scratched gold bracelet and chipped pink nail polish. Mabel? Could it be? A head of red hair faltered behind Mabels shoulder. Marta too? My co-volunteers at the church? We stared at each other, our faces flushing. We oriented ourselves. Martas eyes filled and Mabels streamed. Im afraid I couldnt cry at that moment. It would have been nice but I couldnt get past my fear. When the meeting was called to order, Martas right hand automatically sailed to her forehead to make the sign of the cross before she noticed and slid her fingers through her hair instead.

Mabel and Marta were mothers too. The moms of Teddys and Nells friends. I knew them from the two Catholic churches in the community where wed cleaned or fundraised or held bazaars to pay the enormous heating bills for the high ceilings of Gods house, where the priest presides.

The sensation that I was at Mass dissipated instantly when we rearranged our chairs on that first day. It took only a minute or two. We no longer faced the front. Instead, in a circle, we encountered each other. One of the things about Mass is that people dont have to interact. In rows of pews, you can view the backs of your fellow churchgoers for years and years and never do more to engage with them than shift slightly to wish them peace as part of the liturgy. In our painful O, we had to get to it on the first day. We were to say our names; and when I heard myself say, Hi, Im Eleanor and acknowledge where I was, I felt sudden anguish. I was in fact here, on this seat, in this room. I was introducing myself to this particular group.

After wed completed the enormous task of identifying ourselves to each other, the head social worker introduced herself. Her name was Georgia. She spoke in sometimes gentle, other times insistent tones about the benefits we might expect if we all worked together to share our experiences related to sexual abuse, not only the crime committed in our present family lives but the corruption in our past. There is no unimportant detail, she said. Everything matters.

Slowly, over those first meetings, one group member after another awakened from a long sleep. On one occasion, a tiny kernel of information resonated so emphatically that my eyes snapped open. I understood. I recognized. I knew what the speaker was saying. Even though there were differences among us, there were also recurring religious, cultural, and social motifs that wed all inherited and that bound us together, good and tight. During those early meetings, I noticed that despite Georgias challenging us to become risk-takers, each of us stuck to polite traditional vocabulary as we recalled our own histories of being tampered with or touched inappropriately by troubled individuals. Our soft blanketing language minimized the effect of molestation and thus offered protection to our abusers. After all, the molesters were often people we knew and perhaps had loved. It gets complicated.

Indeed, at the end of the first meeting I was grateful for one rather grisly fact: that the molester in my family was not my son. With Mabels brief testimony about her eldest sons molestation of his younger sister and brother, I felt the one emotion Id never expected to feel in this room. I had it easier. Imagine the pain of having given birth to the victimizer of your other children.

Back in the safe confines of my kitchen that first night, I sauted floured drumsticks in olive oil and, while they were browning, finished a lesson prep for the next mornings class. Id have my work done before Teddy and Nell arrived home. The children would be glad to eat chicken and rice tonight. Teddys gym teacher had asked my teenager to tell me that I should serve more meat at home, that red kidney beans and oat bran were used in the old days to stuff pillows and mattresses, not to nourish growing young men. It had hurt to hear what I perceived to be an accusation rather than a suggestion. I was sensitive to criticism about my care of my children. Very sensitive. Funny how all along Id believed there was nothing this mother did not know about her two favorite people.

Next page