Quite soon after I came to the West Country, more than half a lifetime ago, I realised what an incredible part of Britain was now on my doorstep. My first physical explorations of Somerset confirmed this impression, with even more fascinating discoveries coming to light from time spent in the Somerset Studies Library and the County Record Office at Taunton delving into the events and people that had shaped its history. I owe much to the staff in those places.

Hoping to share the fascination I was finding, I wrote a small book, Exploring the Smaller Towns of Somerset , half a dozen other works on diverse local subjects and a series of Town Trails and other articles for the former Somerset Magazine . Roy Gallop was an invaluable partner in all these efforts.

This book dips into the files of information I have collected over the years and attempts to present a selection of some of the most unusual, intriguing and entertaining items they contain. Nicola Guy, Declan Flynn, and the staff of The History Press have, as always, been immensely helpful and supportive. Tess Green has generously contributed information on two subjects and my sister, Maureen Etheridge, has kindly cast a tutored eye over my efforts. To these, and the many past contributors to the Notes & Queries columns of the Somerset Herald I have scrutinised, I am extremely grateful. Any shortcomings in the outcome of all this are entirely mine and are much regretted.

The illustrations are from my own collection, except where otherwise indicated.

Contents

ABBOT WHITINGS MARTYRDOM

In the year 1539 a sad drama came to its dramatic climax on the summit of Glastonbury Tor. The story had been building up for the best part of five years, over which period the consequences of King Henry VIIIs break from the Church of Rome had become more and more apparent throughout England. Its size and importance had preserved Glastonbury Abbey for a time, but even such an eminent and well-run foundation could not escape the process of dissolving the monasteries which was yielding such riches for the monarch and those he favoured.

To justify the process there had to be scapegoats and, quite undeservedly, Glastonburys abbot became one of these. Lord Russell, who was in charge of the affair, described the outcome in his subsequent report to Thomas Cromwell, writing: that on Thursdaye the 14th daye of this moneth the Abbott of Glastonburye was arrayed, and the next daye putt to execution with two other of his monkes for the robbying of Glastonburye Churche, on the Torre Hyll next unto the towne of Glastonburye.

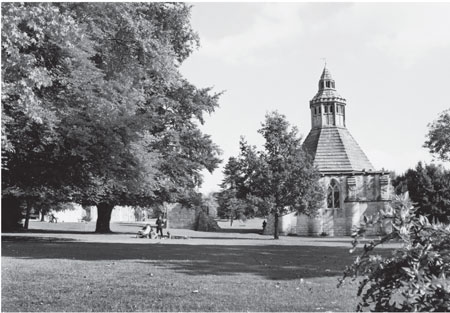

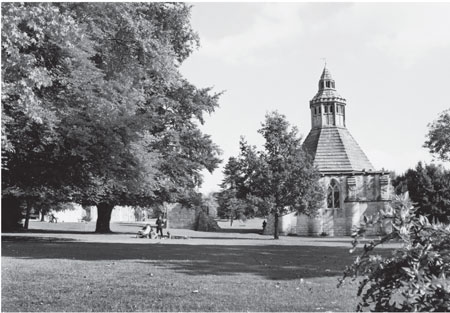

Although much of the former Glastonbury Abbey is now in ruins, the erstwhile Abbots Kitchen conveys some idea of the splendid place it must once have been.

The abbot referred to was Richard Whiting, a man of modest origins who had studied at Cambridge, been ordained priest and then given an appointment as chamberlain at Glastonburys famous abbey. He seems to have attracted the favourable attention of Cardinal Wolsey who, in a surprise decision, elevated him to the highest position in that great religious establishment, that of abbot. Taking over in 1524, Abbot Whiting seems to have been an effective leader, carrying out the religious and pastoral duties of the abbey well, and effectively managing its large establishment, its great landownings and its many satellite houses. Forty-seven monks witnessed his election as abbot and supported the abbeys works with more piety and discipline than was apparent at some religious foundations.

Inevitably, all this was to change in the massive upheaval which followed Henry VIIIs divorce from Queen Catherine of Aragon and his consequent break with the Pope and the Roman Catholic religion. Whatever Abbot Whitings personal reservations about the kings chosen means of changing the nations religious allegiance and practices, he duly appended his signature to the tool chosen for this, the 1534 Act of Supremacy. In the following year, Thomas Cromwell was appointed Vicar General and, interpreting the kings wishes, instigated a survey of Englands religious houses. As a result of this, Glastonbury Abbey was inspected by Dr Richard Layton who reported that there was nothing notable to say about it. It became increasingly clear later that Layton could not find any real fault with either Glastonbury or nearby Bruton.

The Act for the Submission of the Clergy and other legislation in the 1534 package was supplemented in 1535 by a statute governing the dissolution of the smaller monasteries. These were the simplest prey, and Cromwells commissioners no doubt saw them as easy to find fault with and to relieve of their land and treasures. So began a process of pensioning off the inoffensive clergy and making an example of the obdurate, coupled with lining the pockets of the monarch and his chosen beneficiaries. Richard Whiting must have watched this process with growing concern and he tried to protect his own establishment by frequent gifts and written appeals to those with influence. To no avail.

Dr Layton appears to have felt that Abbot Whiting was a man without fault, which was not the direction in which his masters wanted to go. Some of the larger monasteries had already surrendered themselves voluntarily, and a 1539 Act legitimising this also gave powers to dissolve the remainder, especially if treason or any other crime was discovered. Whiting and his abbey were now doomed. On 7 April he wrote a pitiful letter to Cromwell arguing against a summons to London, pleading that for some time he had been greatlye diseased with dyvers infirmyties, but it failed to deter Cromwell, influenced not only by his monarch, also but by the amount of confiscated wealth rolling in.

Already the religious houses of the West Country had yielded up around 500 ounces of gold and 45,000 ounces of silver and silver plate, and there was more to be had at Glastonbury. More commissioners came down and began the authorised looting there, but the abbot appears to have been left alone until a surprise visit by a group of commissioners on 19 September 1535, when Whiting was told that the abbey would close. He was taken from his house at Sharpham and confined in his lodging at the abbey. He was soon escorted to London and there confronted with prepared charges, never fully disclosed, before being returned to Glastonbury under guard. The opportunity had been taken to search the abbots personal possessions in his absence and damning evidence was allegedly discovered in the process. Whether or not it had been conveniently planted there is a matter for conjecture.

Even less information was forthcoming about a trial of Abbot Whiting which was staged before a jury at Wells on 14 November, but certainly no effort had been spared by Cromwells emissaries to extort damning testimonies against him from some who feared for their own safety. The outcome of the examination was certain and swift. The verdict condemned to death was widely publicised, but there was no publicity for the trial evidence and process.

After being taken back to the abbey under escort and spending the night there, Richard Whiting, his treasurer John Thorne and the sub-treasurer Roger James were roused the next morning. The day was destined to be their last. In a sad and degrading spectacle the three unfortunates were placed upon hurdles which were dragged by horses up the steep slope to the summit of the tor.

Next page