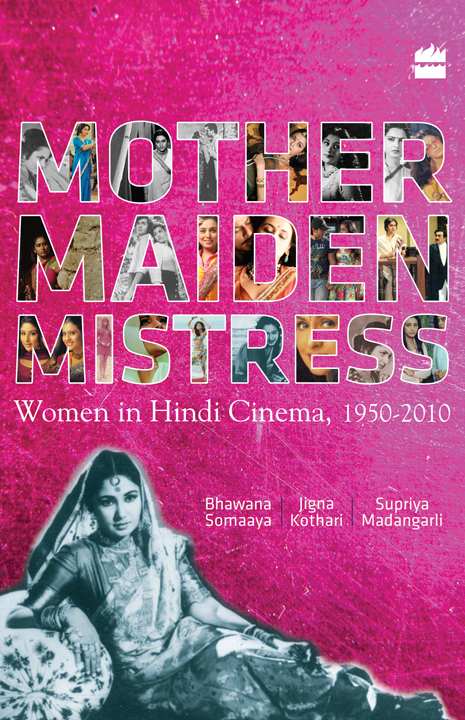

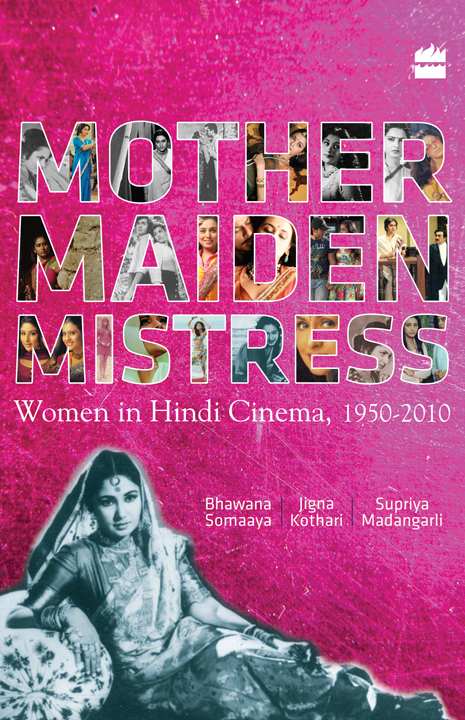

M OTHER M AIDEN M ISTRESS

W OMEN IN H INDI C INEMA, 19502010

Bhawana Somaaya

Jigna Kothari

Supriya Madangarli

HarperCollins Publishers India

New Delhi

To our parents.

C ONTENTS

T he third of May 1913. The Coronation Cinematograph Theatre, packed to the hilt, watches a bevy of women in wet saris cavorting around a fountain. The film is Raja Harishchandra, Indias first feature film, and the women are men in wigs and costumes. This was not what the director Dhundiraj Govind Phalke had wanted. He had hoped to find real women to play the role of Queen Taramati and the other female characters in the film but had failed. He had advertised in the newspapers, and even visited women in the red-light area. But the women there didnt fit into Phalkes vision for they were dark, ugly and emaciated persons. Queen Taramatis role was reluctantly given to a young man, Anna Salunke, who became quite well known for his female impersonations, playing both Sita and Ram in Phalkes Lanka Dahan.

Sometime later, when Phalke heard that a travelling drama company was going to pull up its tents for six months, he requested the director to lend him two of his actresses for his next film, Mohini Bhasmasur. Says Kamlabai Gokhale (ne Kamat), who was all of fourteen years at the time, Phalke Saab had heard that our company was closing down for six months. So he came and requested our director to allow my mother and me to act in his film. Thats how I got to play the lead role. My mother played Parvati.

Kamlabai and her mother Durga thus became the first women to act in an Indian feature film, one of the many testaments to the pioneering spirit of Phalke. He was also the first to set up a studio Phalke Films a space which included shooting stages, post-production labs, residential areas, a canteen and apparently even a zoo. The company later became the Hindustan Film Company when Phalke accepted an offer from some textile industrialists of Bombay to run the studio as a partnership.

A scene in Paresh Mokashis Harishchandrachi Factory (2009), a Marathi biopic which lovingly recreates the era, has Phalke and his family, having watched The Life of Jesus Christ, discuss what to call what they had had just seen: chitra malika a photo serial; pardevarchi natak a play on screen; or halti chitra moving pictures. In those early days thats what cinema was a series of moving pictures put together with a basic shooting script. The camera was static and all the action happened inside the frame. The stories told were the ones audiences were familiar with mythology, folklore and stories they grew up on.

However, as the industry grew, cinematographic practices began to change. The 1920s saw the film business booming, with exhibitors targeting not only cities but regional centres and villages too. Films often had bilingual cue cards dialogues written in Urdu, Hindi, Marathi and English giving the exhibitor the flexibility to traverse between Bombay and villages in the interiors of the country. The Hindu in 1926 writes of a cinema car attached to trains that would have the required equipment and would busy itself regularly touring all along the lines, giving open-air shows to audiences varying from 1,000 to 10,000.

In the cities, the early shows were held in marquee tents, then in converted theatre halls. In Bombay, it was the Opera House or the premises of buildings with enough space like Framji Cawasji Institute at Dhobi Talao, Watsons Hall or the Town Hall. By the 1930s, with the advent of sound, the business of cinema in Bombay had exploded with eighty-five film companies with well-equipped studios. Correspondingly, exhibition spaces came up, art-deco-style theatres like Regal (1933), Plaza (1935), Central Cinema (1936), Broadway (1937) and Eros (1938).

The world changed radically for film industries across the globe in 1927, with the release of The Jazz Singer, the first talkie, which starred Al Jolson and which had the memorable tag line: See him and hear him sing. It was only a matter of time before the talkies came to India. On the first day of the release of Indias first talkie Imperial Film Company and Ardeshir Iranis Alam Ara, starring Master Vithal and Zubeida and featuring ten songs Majestic Theatre was surrounded by huge mobs fighting to buy tickets. Black market vendors did brisk business, selling the tickets at twenty times their price. On 2 April 1931, the Bombay Chronicle noted that with due restraint and thoughtful direction, the players could by their significant acting and speech evolve dramatic values to which the silent cinema cannot possibly aspire.

Sound raised the question of language. Silent films allowed one the freedom of holding up title cards that could be customized to the language of the audience. At times there were narrators who became performers in their own right, and who would read out the cards in the particular dialect of the region. With sound, there was a need for dialogues, and the directors turned to old friends of the silent era eminent playwrights of the UrduParsi theatre of the time like Aga Hashr Kashmiri (Chandidas, Yahudi Ki Ladki) and Narayan Prasad Betaab (Miss, Barristers Wife, Keemti Aansoo) who not only wrote story and dialogues but lyrics too. Sound also gave birth to film music. Sound technicians, musicians, music directors and, more importantly, singing actors were added to the roster. To act in a Hindi talkie meant that the actors needed to master the language, which meant training in Urdu and Hindi. Directors scoured the stage to source actors who could orate, pull off monologues, and do justice to the dialogues.

One aspect of women in the early days of Indian cinema needs to be highlighted. It was white-skinned actresses (mostly referred to as Anglo-Indians) who were more popular and in demand, with advertisements of plays often highlighting the presence of a Gori Miss (white lady) or houris (fairies) from paradise. For one thing, films were considered a disreputable business and women from traditional Indian households would not have anything to do with them. In contrast, women of Baghdadi

Ruby Meyers, aka Sulochana, was a telephone operator before she was discovered and introduced in Kohinoor Film Companys Veer Bala (1925) directed by Mohan Bhavnani. One of the reigning stars through the late 1920s and the early 1930s, her claim to fame included the fact that at one point she earned more than the governor of Bombay. Esther Abrahams, aka Pramilla, came to films from a Parsi travelling theatre company. A well-educated girl, with pre-university art certificates from London, she became famous for her roles as a vamp and a stunt star. Patience Cooper, who used her own name, worked as a dancer for a Eurasian troupe, the Bandmanns Musical Comedy, and also with Madan Theatres and the Parsi Theatrical Company before being introduced to films. Her roles were mostly of a nave, sensuous woman caught in the web of passion. She was famous for her role in Madan Theatres Pati Bhakti (1922), as the devoted and submissive wife Leelavati whose antithesis was the other woman played by an Italian actress Signora Minelli who was apparently dressed in semi-transparent costumes.

Renee Smith also worked as an actress with Madan Theatres before assuming the pseudonym of Seeta Devi in Himansu Rais Prem Sanyas. Other actresses included Iris Gasper, aka Sabita Devi; Susan Soloman, aka Firoza Begum; Effie Hippolet, aka Indira Devi; Bonnie Bird, aka Lalita Devi; Beryl Claessen, aka Madhuri; and Winnie Stewart, aka Manorama.

Next page