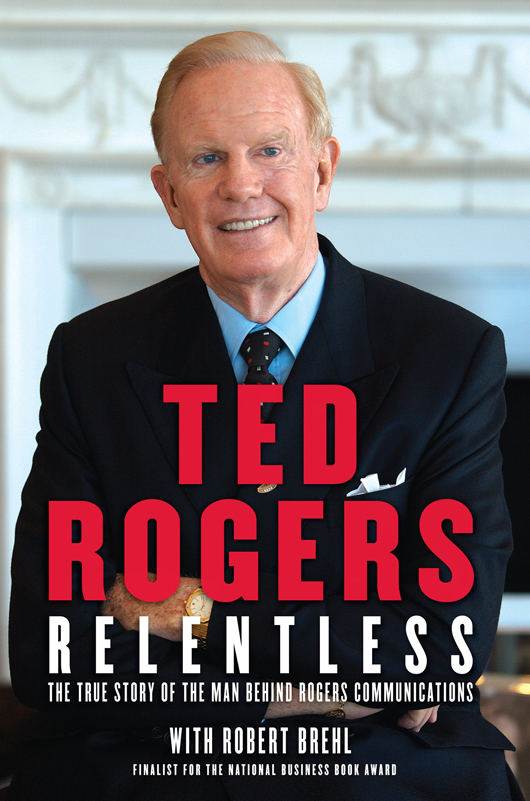

To my wife, Loretta, and to Lisa, Edward, Melinda, Martha and the future generations of Rogers. We did it all for the family.

ESR

To Cobi, Aidan and Charlotte. And to Paul and Eric; I can still hear your encouragement, though neither of you is here to see the finished book.

RGB

Prologue

THE ART OF THE DEAL

It was a sweltering hot July day in San Antonio, Texas, in 1982, when Phil Lind and I arrived. We were in town for a crucial meeting to renegotiate cable rights with Angelo Drossos, the owner of the San Antonio Spurs basketball team. As we headed downtown and drove past the Alamo, I thought about how tough this meeting would be. We were saddled with a bad deal that was sucking more than $1 million a year out of the company. Like Davy Crockett and his men at the Alamo, we just couldnt hold out much longer. We had to get this ironclad, 15-year deal changed.

Drossos held all the cards, and he knew it. Drossos was an entrepreneurial legend in San Antonio, a second-generation Greek American who started out as an Arthur Murray dance instructor and went on to make his fortune in car dealerships, restaurants and pretty much anything else he backed in and around San Antonio. He was known as one of the toughest negotiators in the Lone Star state, with a reputation for being tighter than bark on a tree when hammering out a deal.

Renegotiating this deal was essential for the long-term success of Rogers Cable in the United States. Had we failed to get a new deal, would we be put out of business? No, not likely. But with double-digit interest rates in the early 1980s and our rapid expansion forcing us to borrow more and more, we just couldnt afford to waste money. This deal might not have had a direct impact on our Canadian operations, but it might well have pushed us out of the U.S., a market we would vacate eight years later on our own accord with a $1.5 billion profit. We used that money to invest in the emerging wireless industry in Canada. In hindsight, this meeting takes on even greater meaning than I had thought at the time.

In those days, the cable TV industry in the United States was in a gold rush frenzy. Its largely forgotten now, but cable in Canada was a decade or more ahead of the U.S. in its development. Just as the demand for American programming spurred the growth of Canadian cable in the 1960s and 1970s, it was HBO and my friend Ted Turners WTBS Super Channel and CNN that ignited U.S. cable growth during the Ronald Reagan years. Those were some of the most exhilarating years for cable, days that will never return.

For cable operators like us, there were two ways to get in the U.S. game back then: either go to various city councils around the country and apply for the cable franchise in that area; or buy up fledgling cable systems that had been awarded the franchise already. Phil Lind, who was then chairman of our U.S. operations, and his team had won scores of these franchises from local councils in cities in California, Oregon, Minnesota and elsewhere. And with Colin Watson, president of our cable operations, we were building out systems like mad across the U.S.

San Antonio was different. In this case, we had bought an existing franchise. The city was growing so fast and furious that the franchise looked like a gem, notwithstanding the lopsided and unfair contract with the Spurs basketball team. In a nutshell, the contracts terms dictated that we pay the Spurs a minimum of $1 million a year to carry their games on our cable system for 15 years. We had to pay the Spurs every year, regardless of whether we had 100 or 1 million paying customers. And the more customers we had, the more wed have to pay. Looking back, I can see why the previous owners structured the deal this way. It was the early days of pay-per-view and there was a mentality not unlike the late 90s dot-com euphoria. The other reason they took Angelos bait was that this deal ensured that the San Antonio council would issue them the cable franchise. As I said, Angelo was a shrewd negotiator.

Dont get me wrong, pay-per-view has been extraordinarily successful, both for cable operators and for customers who receive the programming they want when they want to watch it. But it took some time to get there, and in the meantime Rogers Cablesystems was shelling out millions of dollars to the Spurs for literally nothing in return.

In San Antonio, we had a terrific young woman named Missy Goerner working for us. She still works for us today on U.S.-related issues, such as programming rights. I had called Missy a while back and said the deal with the Spurs was too onerous, that we would have to get out of it. She gulped and told me it was all laid out in black and white. In fact, she said, our payment was overdue and we owed Angelo $1 million right now. Over the next few weeks, Missy gathered information on the Spurs and, in particular, on Angelo, the majority owner (he had 32 minority partners, including car dealer Red McCombs, who now owns the NFLs Minnesota Vikings). Even with all those partners, Angelo was clearly in charge, and I knew we would have to do something big to get him to renegotiate a signed deal.

Missy turned up some great information. Angelo had a gambling, carny-like personality. He is widely credited with the three-point line in basketball that has added so much excitement for fans. He once won one of his players in a tennis match with another owner, according to Missys information. There was another legendary story about his spat with Commissioner Mike Storen of the old American Basketball Association (ABA), which later merged with the NBA. Storen made a ruling against the Spurs that Angelo thought was patently unfair. Sports sections in newspapers across Texas and around the United States reprinted the wonderful missive Angelo sent to Commissioner Storen: F youstronger message to follow. The matter went to court and Angelo won.

We had our work cut out for us. Missy set up a lunch meeting with Angelo in his office in the penthouse of one of San Antonios tallest office towers. Because Phil and I sometimes have punctuality issues, Missy warned us numerous times in briefing notes and on calls that we must not be late because Angelo was absolutely obsessed with punctuality.

Well, we were running late. Missy was already in Angelos office. She told me later that Angelo was very cordial to her, but firm. He let it be known very clearly that this was going to be an unpleasant meeting and if these Canadians thought that they were gonna come in and push him around then they were in for a real shock, Missy recalled. At exactly 12 noon, the lunch was wheeled in. Then, at two minutes past noon, Angelo told Missy: Theyre late. Lets start eating. He took the warming covers off not only his plate, but our plates as well. The two of them ate in silence. It was awkward and I could see him get madder and madder by the minute, Missy said.

Finally, at 17 minutes after noon, we arrived. Angelos face was a red inferno. He could barely shake our hands he was so mad. Angelo had a horrible temper but he was also a total gentleman in front of women. It was a good thing Missy was in the room. I apologized for being late, but it didnt seem to help. I figured I might as well cut to the chase and tell him the deal was problematic and unfair. Later, Missy told me she was beside herself at this point watching Angelo seethe. She figured I might have blown it. All Angelo saidover and over againwas, You owe me a million dollars.

Yes, yes, I said. I know were a bit late, because of the transfer of operations.

And Angelo just repeated: You owe me a million dollars!

Youre right, youre right, I said. I brought it with me.