A LSO BY F RANCES K IERNAN

Seeing Mary Plain:

A Life of Mary McCarthy

For Howard Kiernan and Linda Gillies,

who made this book possible

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

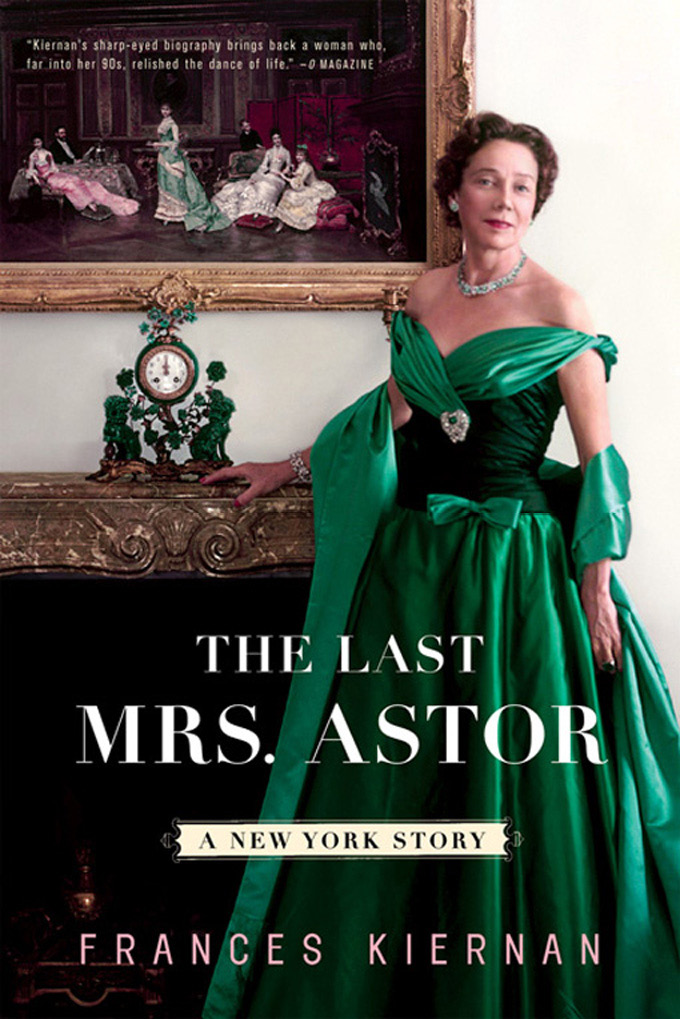

I first met Brooke Astor on January 7, 1999, when a friend brought us together for lunch at the Hotel Carlyle. The lunch was part business and part pleasure. Over the course of several years our mutual friend had gone from escorting Brooke Astor to parties to staying with her in the country. Although he was exactly fifty years younger than Mrs. Astor, the two of them were a perfect match. Both were funny and direct and quick to get to the heart of the matter. We were having lunch at the Carlyle because this friend, John Hart, believed I could help Mrs. Astor get the wonderful stories she told down on paper. A couple of years earlier, Mrs. Astor had officially closed the Vincent Astor Foundation, while I had recently finished my book on the writer Mary McCarthy. As John saw it, we were both at loose ends. Of course he didnt put it quite that way. The lunch was billed as a chance for two of his favorite people to get to meet each other. If anything came of it, that was all the better. But the point was to have a good time.

In preparation for the lunch John would have made sure to tell Mrs. Astor that I had worked for many years at The New Yorker. There was no need for him to tell me about Mrs. Astor. Id been reading about her for years. In a crowd I could have picked her out with no difficulty. In Cincinnati or Detroit she might have gone unrecognized, but in New York she was famous.

Lunch was set for one and I made sure to arrive early. It was a typical first week in January. Outside, it was cold and gray, with a hint of snow in the air, but as I approached the steps that led down to the restaurant the first thing that caught my eye was an enormous spray of crab apple branches and quince. Once the matre dhtel learned I was part of Mrs. Astors party, he ushered me to the best of four horseshoe-shaped banquettes that backed onto this extravagant tribute to spring. If I looked to my right, I had an unimpeded view of the entrance. Mostly I studied the menu, but occasionally I would glance up and see some well-dressed couple being led past me to a less desirable table.

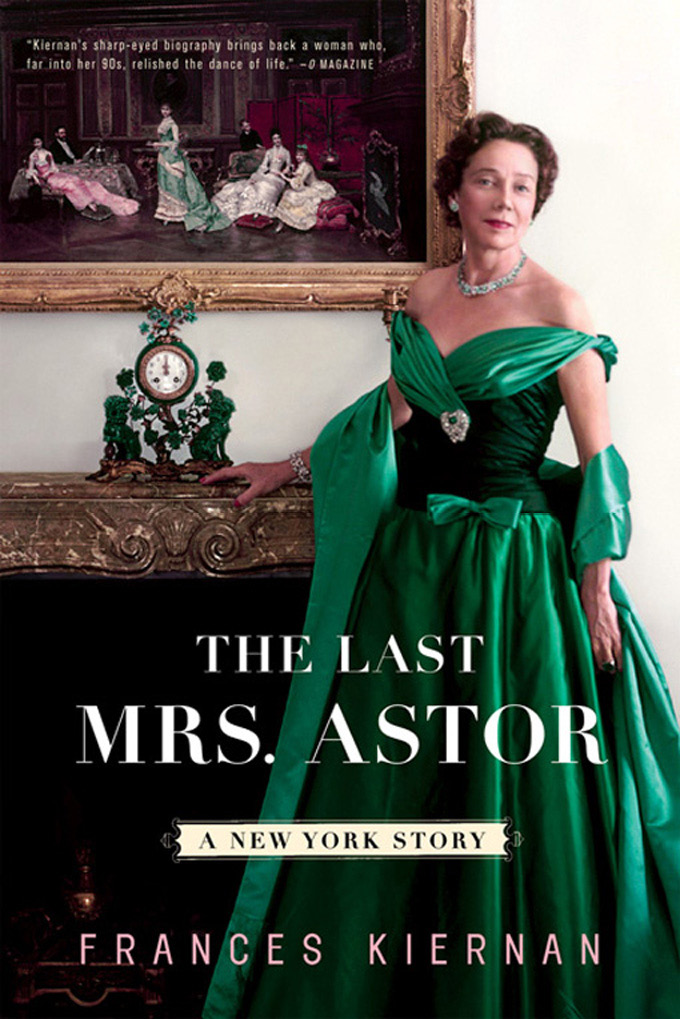

At precisely one fifteen, Mrs. Astor entered the restaurant on the arm of John Hart. You couldnt exactly say she made an entrance, but when she appeared at the top of the short flight of stairs leading down from the vestibule, all eyes turned in her direction. Some of this had to do with the way the matre dhtel fussed over her ever so slightly as he grasped her free elbow to help her to the banquette. Part of it was what I think of as star power. And part of it was the way she was dressed. By the time John had gotten the three of us settled, with Mrs. Astor in the middle, Id begun to covet everything she was wearingthe smart loden-colored felt hat, the pretty green silk blouse, the green windowpane-plaid suit, the triple string of gum-ball-sized pearls, the diamond starburst on her left shoulder, and the jade and diamond earrings that set off her green eyes. I had been prepared to admire her, but I hadnt been prepared to find her pretty or chic.

Photographs didnt begin to do Mrs. Astor justice. Part of what made her so attractive was the delicacy of her coloring. Part of it was the way she brought all her attention to bear on the person she was talking to. Part of it was the magic worked by charm. She was an accomplished seductress. That day, whether to please John Hart or for want of anything better to occupy her, she set out to seduce me. Nothing she said was especially witty or insightful. Indeed, Im not sure Id remember any of it if I hadnt written up some notes that same evening. But at the time everything she said seemed delightfully fresh and candidremarkably so, when you considered that she was ninety-six years old.

That day, whatever Mrs. Astor ordered from the long menu, I ordered, too. I think it was a crabmeat salad. Neither of us paid much attention to our food. For one thing, I dont think she had much of an appetite: contributing to the stylish impression she made was the fact that she was impossibly tiny. For another, she had trouble hearing. John had made sure that I was seated on her right, by her good ear, but, even so, I had to speak up, and sometimes repeat myself, and she had to bend close to make out what was being said.

Mrs. Astor led off by asking about my time at The New Yorker . Then she asked me about my book, which was scheduled to come out the following year. The subject of my book seemed to interest her not at all, even though I had learned from Renata Adler that she had put up Mary McCarthy for the night when McCarthys beautiful white Mercedes convertible had broken down near her place in Maine. The thought of two women so differentone known for her tact and good manners, the other for her sharp tonguespending one night together conjured up all sorts of tantalizing possibilities. At one point Id asked John Hart if I could talk to Mrs. Astor about that visit and word had come back that she had nothing to say on the subject. Mary must have stolen a toothbrush, her stepdaughter had joked. I tended to think nothing quite so dramatic had transpired. Mrs. Astor was of a generation that believed when you had nothing good to say you did best to keep your mouth shut.

At lunch that day Mrs. Astor did her best to put me at my ease, the way any experienced older person does with a younger person who is shy. When conversation flagged, she asked me another question. It was a method I myself had used many times. We talked again about The New Yorker , which had published three of her poems. Then we talked about her dear friend Brendan Gill, who had died one year before. I noted that she had been the only speaker at Brendans big memorial who mentioned his wife. That made her laugh.

Mrs. Astor brought up someone we knew in commonan old friend of hers who had recently married a woman half his age. She made no bones about what she thought of his wearing jeans for the wedding ceremony and his going around beforehand saying he wasnt so sure he wanted to go through with the whole thing. That led her to talk about her terrible first marriage. She wondered why it hadnt left her embittered. She seemed bemused by that fact. She spoke of her honeymoon: of the grooms not having a dinner jacket so they could go down to the main dining room and of his going down alone to the bar only to come back drunk. But that was only the beginning. Some six months later when they were up in Maine she had terrible abdominal cramps and assumed she was having a baby, but when the doctor examined her he determined she was still a virgin.

She told me that the first American president she ever met was Harry Truman and her favorite was Ronald Reagan. On occasion the Reagans would have her down to stay overnight at the White House. He was fun and Nancy was strong . She said shed gone down to the Clinton White House the year before to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This led her to a discussion of Clintons being caught in a lie about Monica Lewinsky. She was reminded of the time shed been caught in bed by her mother with chocolate smeared on her face and had been foolish enough to try to deny it. Lying is not efficient, we agreed. You cant keep track.

She confided that she was hoping to go to St. Petersburgto take a boat and go ashore to see all the palaces. It would be more pleasant that way. This reminded her of a recent visit abroad. Shed been staying with friends at Hatfield, one of the great houses of England, when shed had the terrifying experience of finding herself locked out of her room late at night. She described waking and hearing dogs barking outside and wanting to let them in and slipping downstairs in her nightgown and having the door to her room shut behind her; finding no dogs when she opened the big front door and hearing the click of a timer as all the lights in the house shut off; making her way in the dark back up the stairs and down a long hallway and tripping and falling and banging her arm; finally calling for help and getting no response; and then crawling along the hallway until she was able to push open a door and let herself into an unaired room, where she wrapped herself in a rug for warmth and fell asleep, curled atop the damp mattress of an unmade bed.

Next page