NEB 009

First published in the UK in 2022 by Nine Eight Books

An imprint of Bonnier Books UK

4th Floor, Victoria House, Bloomsbury Square, London, WC1B 4DA

Owned by Bonnier Books, Sveavgen 56, Stockholm, Sweden

@nineeightbooks

@nineeightbooks

@nineeightbooks

@nineeightbooks

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-7887-0561-5

eBook ISBN: 978-1-7887-0562-2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Publishing director: Pete Selby

Senior editor: Melissa Bond

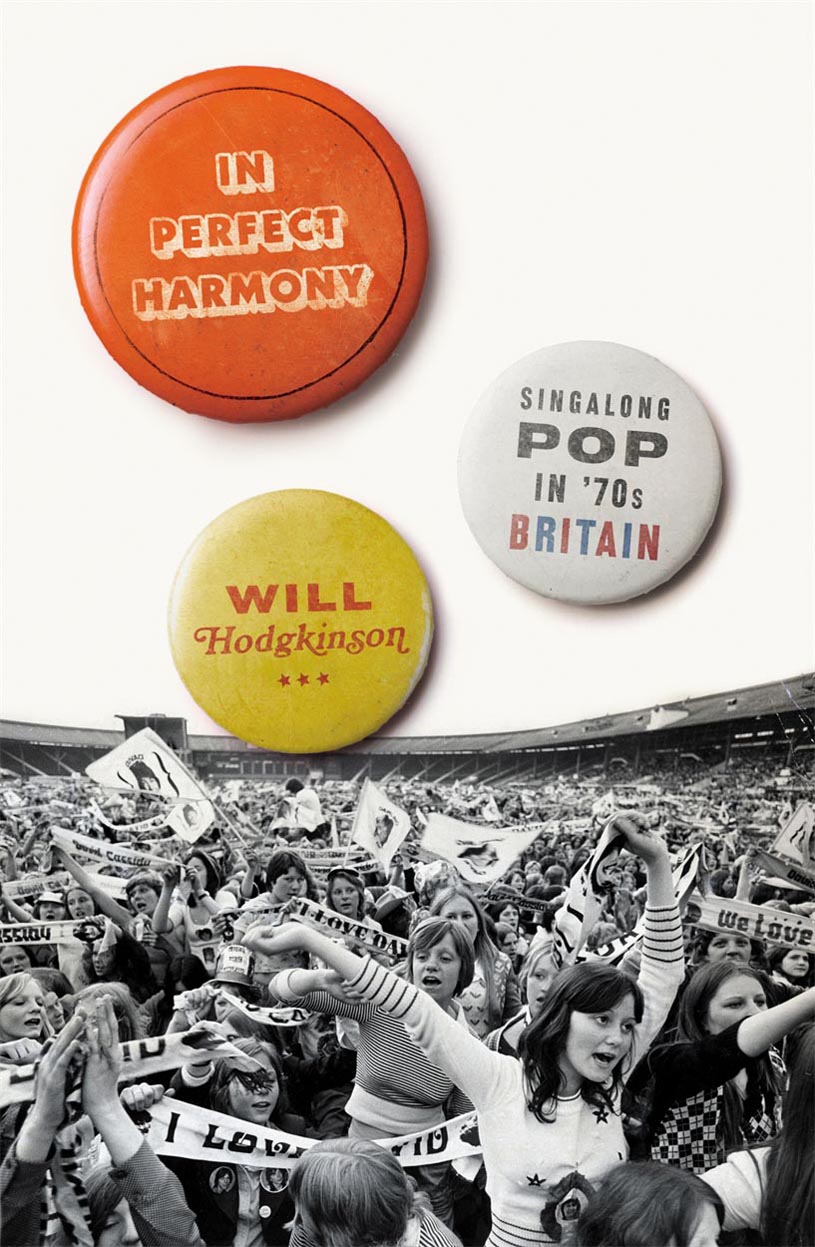

Cover design by Steve Leard

Cover image ANL/Shutterstock

Typeset by IDSUK (Data Connection) Ltd

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Text copyright Will Hodgkinson, 2022

The right of Will Hodgkinson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright-holders of material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publisher would be glad to hear from them.

Nine Eight Books is an imprint of Bonnier Books UK

www.bonnierbooks.co.uk

To Lawrence, for the inspiration

Contents

What weve tried to do with Grandad is incorporate pop trends with something that appeals to everyone. Kids, pop fans, adults, everybody.

Herbie Flowers, New Musical Express, 16 January 1971

Back in the early 90s, Britains charity shops were awash with mass-produced records from twenty years back that pretty much nobody wanted. You could wander into any Oxfam or Sue Ryder on the high street and pick up a copy of James Lasts Happy Hammond, Blue Minks Melting Pot or countless Top of the Pops albums featuring cheaply recorded cover versions of the hits of the day. Big singles like David Essexs Rock On or the New Seekers Id Like to Teach the World to Sing (In Perfect Harmony), in their own way just as sophisticated and groundbreaking as the most sought-after buried treasure, lined up in mildewed stacks, unloved and abandoned, stuffed into plastic crates beneath rows of unremarkable plain blue shirts from Marks & Spencer. Rarely did the price tags go beyond the pound mark. These records belonged to a browning, nicotine-stained world of cabaret nights, working mens clubs and Saturday night variety shows, of cheap glam and rich melody, where entertainment meant exactly that: a brief distraction from the realities of living. The 1980s, with its brash aspirations and material possibilities, killed it all off.

Fast forward three decades and humming along to the bouncy melody of Chicory Tips Son of My Father on a drive down to Cornwall, a song that as far as Im aware has not inspired many lengthy treatises from the critical minds of our day, got me thinking: isnt a radio hit that appealed to millions back in 1972 socially significant? If a song chimed with the mood of the nation, doesnt it say something about the time and place it came from? Dare I suggest that Leap Up and Down (Wave Your Knickers in the Air) by St Cecilia might reveal more about contemporary attitudes than, say, We Are All Prostitutes by the Pop Group?

Thats where the seeds of this book took root: the idea of taking seriously the singalong pop of 70s Britain, which has so far not been taken seriously at all. This is the music that went beyond style and image and had a quality that made it relevant and accessible to everyday people, which is why, by 1971, singles were outselling albums for the first time since the early 60s. It might seem like a preposterous endeavour to link Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep by Middle of the Road, a Scottish hotel cabaret band who found themselves marooned in Italy, with Conservative PM Ted Heaths dream of European integration. And it might come across as a bit of a stretch to argue that Slades Merry Xmas Everybody can tell us more about the three-day week of winter 197374 than any number of sociological investigations into the uneasy relationship between the unions and the British government. But anything that cuts across demographics has something to say about the era it belongs to and so began what this has become: a social history of singalong pop in 70s Britain.

Thinking about the affordable 45s that went out to the kids, the teenagers, the mums and dads and other people who never managed to get hold of the debut album by the Velvet Underground, I realised the decade was bookended by two songs that, though massive hits, are now considered to be among the most hideous novelty singles ever inflicted upon humanity: 1970s Grandad by Clive Dunn and 1980s Theres No One Quite Like Grandma by the St Winifreds School Choir. Are they really that bad? With its chiming ding-dong melody and air of wistful toy town nostalgia, Grandad isnt so different from early Pink Floyd. Theres No One Quite Like Grandma is certainly cloying, but the lyrics have relevance to families uprooted and dispersed by social mobility; a new phenomenon for working-class and lower-middle class people at the time. The more I thought about it, the more I realised that this is what I had to do: take a fresh look, to misquote those singalong sensations the Wombles, at the things fashionable folk left behind.

There were certain figures I knew from the start were integral to the story. Marc Bolan was the first major pop star to abandon the hippy underground and go for the kids, bashing out three-minute masterpieces that recalled the golden age of rock n roll while dazzling a young audience with his glitter wizardry along the way. The voluble figures of the glam movement Bolan inspired certainly needed to be included, but not all of them: no to the art-school sophistication of David Bowie and Roxy Music (although I could allow them the odd cameo), yes to the teenage rampage of Sweet, Mud and Suzi Quatro. There was a whole secret society of backroom songwriters, session singers and pro-level musicians who came up with catchy songs before inventing bands to pretend to play them. There were footballers, moonlighting actors and ageing cabaret artistes; even a pair of home-recording enthusiasts from Coventry who scored a massive hit after roping in one of their mums (Mouldy Old Dough, Lieutenant Pigeon). There were songs that both revealed and tackled attitudes to race, gender and sexuality, but in ways that could be enjoyed by pretty much anyone. I was interested in people who were trying to have hits, even if they didnt necessarily succeed: a luckless glam outfit from Portsmouth called Hector, marketed as the worlds first naughty schoolboy rock sensation, certainly felt relevant to the story. The overriding conviction was that I had to go beyond the accepted canon of late twentieth-century popular music and take on the stuff that made it in the life beyond, into the unstylish everyday worlds of playgrounds and prisons, working mens clubs and mobile discos, the front rooms of suburban new builds and the brutalist blocks of the inner cities.

Next page

@nineeightbooks

@nineeightbooks @nineeightbooks

@nineeightbooks